California’s Proposed Drinking Water Program Reorganization: A Primer

What would the shake-up mean for those who currently lack affordable access to safe drinking water?

A shake-up of California’s struggling Drinking Water Program is in the works. What follows is a little history, context, and a few thoughts on what it will likely mean for drinking-water stakeholders—in particular those who have the hardest time accessing safe drinking water.

A history of problems for the Drinking Water Program

Last April, Jonathan Zasloff posted about California’s failure to spend $455 million in federal contributions to the Safe Drinking Water State Revolving Fund (SDW SRF). The California Department of Public Health, which administers the Fund as part of its Drinking Water Program (DWP), had received a Notice of Noncompliance from the U.S. EPA regarding the Department’s failure “to make timely loans or grants using all available drinking water funds to eligible water systems for necessary projects.” The notice identified the lack of “dedicated accounting and financial staff to track commitments, calculate balances, and plan expenditures” (leading, for example, to failure to take into account “at least $260 million in loan capacity” from loan repayment revenues) as one source of problem. Although the DWP submitted, and the EPA accepted, a Corrective Action Plan, many doubt the plan has the power to address ongoing institutional shortcomings.

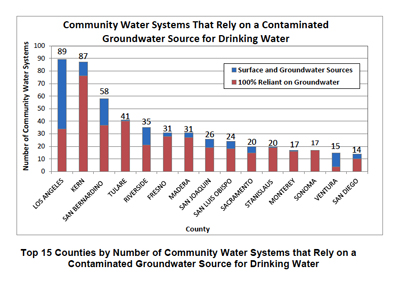

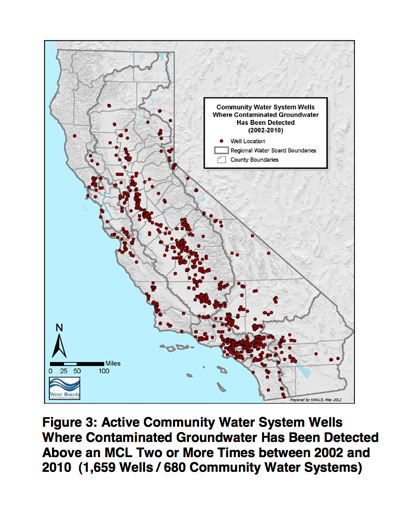

EPA’s reprimand did not come as a surprise. Instead, it followed years of accumulating evidence that the Department of Public Health was not effectively addressing the safe-drinking-water needs of the state’s most at-risk communities. Many Californians (estimates generally range from 200,000 to 2.1 million) lack access to an affordable source of clean drinking water. Those hit hardest reside in small, low-income communities that are solely dependent upon groundwater supplies containing potentially hazardous levels of arsenic, nitrate, or other contaminants. The people least able to absorb extra costs often end up paying twice: once for the questionable water that flows from their faucets and again when they purchase bottled water for drinking and cooking. The severity of the problem prompted California to adopt AB 685, the “Human Right to Water Bill,” in 2012. Among the problems disadvantaged communities have faced in their struggles to overcome barriers to clean drinking water is difficulty applying for and receiving loans and grants from the SDW SRF and other programs.

The shake-up

Against this backdrop, both the California legislature and Governor Brown’s administration have recently floated plans to revamp the DWP, in significant part by transferring it from its current location in the California Department of Public Health to the State Water Resources Control Board (State Board).

First, in January 2013, California Assembly Members Perea (D-Fresno) and Rendon (D-Lakewood) introduced AB 145. Had the bill become law, it would have transferred implementation of the California Safe Drinking Water Act, enforcement of its federal counterpart, and administration of the SDW SRF from the Department of Public Health to the State Board. As things currently stand, the State Board deals with all other (non-drinking-water-related) water quality issues and administers a sister state revolving fund, the Clean Water State Revolving Fund (CW SRF). Environmental justice advocates supported the transfer, while water agencies tended to oppose it. Although AB 145 languished on the Senate Appropriations Committee suspense file, Governor Brown signed several companion bills—including AB 115 which effectively allows “public water systems serving disadvantaged . . . communities” to pursue joint grant funding for joint projects from the SDW SRF—into law.

With AB 145 stalled, the Brown administration decided to move ahead with its own proposal for “Drinking Water Reorganization” through the budget process. Like AB 145, the reorganization would transfer the DWP from the Department of Public Health to the State Water Resources Control Board. The DWP encompasses a technical programs branch and two field operations branches. It regulates public drinking water systems and administers the state and federal Safe Drinking Water Acts and the SDW SRF. Following the reorganization, most functions would be housed in a new Division of Drinking Water on par with the State Board’s existing Divisions of Water Rights, Water Quality, Financial Assistance, and Administrative Services. To maintain public health expertise, the new division head would have a public health background and current Department of Public Health staff would retain their positions under the new leadership. The SDW SRF would join the CW SRF under the Division of Financial Assistance.

Implications of the proposed reorganization

Proponents cite a cascade of potential benefits from relocating the program. On a basic level, the reorganization would preserve the DWP’s inherent strengths, including its public health expertise and locally distributed staff, as well as the program’s “recent positive progress.” Aspects of the program stakeholders generally agree work well (e.g., the existing drinking water system permitting process) would continue essentially unchanged. “Additional steps” would streamline the program, improve its overall effectiveness, and enhance access for disadvantaged communities. The State Board’s general water quality and financial expertise (including dedicated SRF staff) would lend the program robustness. But the greatest boost in benefits would flow from consolidating state water-quality authority, expertise, and funding under one roof. For example, combined management of the CW and SDW SRFs would “optimize and expedite” funding for multi-benefit water projects, making the Division of Financial Assistance a “one-stop shop for water quality infrastructure financing” for disadvantaged (and other) communities. Introducing a drinking water focus at the State Board would not only enable “maximum program efficiencies.” Ideally it would also foster an integrated, synergistic approach to surface-water- and groundwater-quality management that has been lacking in California.

Opponents have raised a variety of concerns about the transfer. For example, they worry that the public health focus and local connections important to the DWP’s work could get lost in the move, that the permitting process could suffer delays and complications during the transition, that effective emergency response processes could be negatively impacted, that small water systems could receive disproportionate funding consideration, that water agencies could be exposed to costs not justified by human health benefits, and that the State Board might start to micro-manage decisions best left to local staff with local knowledge.

A dialogue on reform

To enhance the likelihood of a successful transfer, the Brown administration has pursued an ongoing robust dialogue with a wide range of stakeholders, including those opposed to reorganization. A Drinking Water Reorganization Task Force met 7 times from October through mid-December to discuss critical issues surrounding the proposed transition. The group included 33 stakeholder representatives spanning water agencies, environmental justice advocates and disadvantaged communities, legislative staff, local public health and environmental health officers, and environmental organizations. To maintain good communication, stakeholder advisory groups are slated to continue to meet during and after the transition. In addition, because the State Board must meet and make decisions in public, the switch should increase transparency and provide more opportunities for public feedback going forward.

Governor Brown recently kicked his reorganization plans into high gear with the release of his proposed 2014–15 budget. From the summary:

The Budget proposes to transfer $200.3 million ($5 million General Fund) and 291.2 positions for the administration of the Drinking Water Program from the Department of Public Health to the Water Board. Transferring the Drinking Water Program will achieve the following objectives:

- Establish a single water quality agency to enhance accountability for water quality issues.

- Better provide comprehensive technical and financial assistance to help communities, especially small disadvantaged communities, address an array of challenges related to drinking water, wastewater, water recycling, pollution, desalination, and storm water.

- Improve the efficiency and effectiveness of drinking water, groundwater, water recycling, and water quality programs.

(Details of the proposed budget for the State Board are available here.)

Last week, a public meeting in the state capital featured a panel of Brown administration officials who briefly summarized the proposed reorganization (and their roles in it) before opening the floor to questions and feedback (in person or via email) from members of the public.

Some of the comments highlighted the serious challenges the State Board will face if the reorganization goes forward. For example, multiple commenters expressed concerns about how the State Board will reconcile tensions between Safe Drinking Water Act and Clean Water Act requirements (e.g., disinfection byproducts, deemed pollutants under the Clean Water Act, result from the drinking water disinfection required under the Safe Drinking Water Act). Several emphasized the increasing import of intelligent and cohesive water recycling, groundwater recharge, and groundwater remediation regulations in the face of historical supply variations, an increasingly unpredictable climate, and growing population pressures. At least one water agency expressed hope that the State Board would prioritize “helping rather than fining” water suppliers with contamination problems, arguing that fines would merely strain already limited financial resources, hindering instead of encouraging compliance. While most commenters reiterated well-trodden material, a few brought up important, previously overlooked issues or information, illustrating the need for, and wisdom of, continued public input.

The Brown administration expects to complete a transition plan by mid February. By June 15th, the dust will have settled in the budget process, and the shape of the new Drinking Water Program should become clear.

The $39 billion gorilla in the room?

Transferring the DWP to the State Board may hold significant promise for improving the program’s efficiency and effectiveness, however, it is not a cure-all for California’s drinking water woes. As Jonathan pointed out last April, the state’s current and projected drinking-water-related capital infrastructure needs are huge (on the order of $39 billion through 2026, including $3.5 billion for small community water systems) and “[p]ublic funding sources to address groundwater supply and contamination issues are limited.”

Even though the gains wrought by a new Division of Drinking Water at the State Board and consolidated management of the state revolving funds are unlikely to overcome this funding gap, they can begin to make a big difference were it counts: A thoughtfully planned and executed reorganization will enable effective triage, prioritizing access to safe drinking water for those most in need and facilitating cost-effective solutions for all.

Reader Comments