EPA’s Return to Bush-Era Clean Air Act Reforms Sacrifices Agency’s Duty to Protect Environment, Ignores the Law

Quiet changes buried behind the big de-regulatory headlines spell disaster for the environment

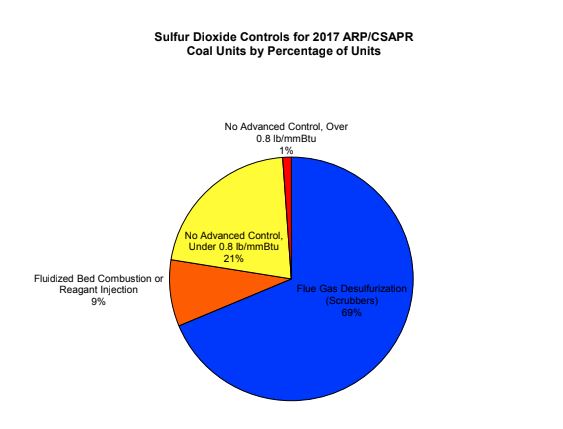

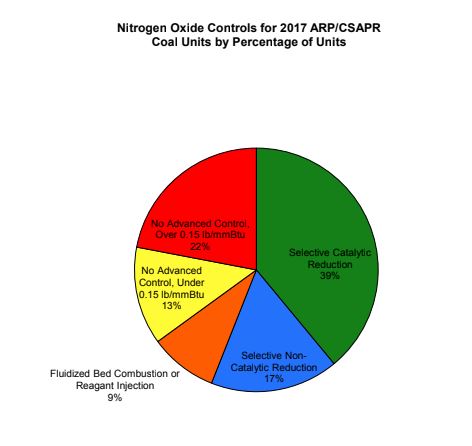

As I explained back in August, the Trump Administration’s proposed Clean Power Plan replacement (the “Affordable Clean Energy” or ACE rule) came with a significant change to how the EPA has traditionally interpreted the Clean Air Act’s New Source Review (NSR) provisions mandating pre-construction environmental review and the installation of air pollution controls to offset emission increases. In my previous post, I outlined the practical dangers of the proposed change: effectively, the Trump EPA is proposing to exempt polluting equipment at coal-fired power plants from undergoing legally required environmental review before upgrading to comply with the ACE rule’s energy efficiency standards. Since coal-fired plants are filled with aging equipment that pre-dates the 1977 Clean Air Act amendments, EPA’s own data shows 35% of coal-fired plants have no control equipment at all for NOx emissions, 22% lack control for SOx emissions, and more than 80% of coal-fired plants have emission rates exceeding those typically required under NSR. In the normal course of things, this grandfathered equipment would either be retired and replaced with new equipment subject to NSR, or be upgraded through a modification triggering NSR. Instead, the Trump EPA is seeking to give these aging plants a golden ticket: upgrade your equipment without undergoing environmental review, and extend the expected lifetime of these pollution-spewing equipment for decades.

The sneaky proposal the Trump EPA is attempting to slip in to exempt these coal plants is to change the calculation methodology for when NSR is triggered. Traditionally, EPA has looked to potential increases in the cumulative annual emissions, but now the Trump EPA wants to look to the hourly emission rate: so long as a modification is not expected to increase the average hourly emissions, NSR would not be triggered. The problem with this methodology is the near certainty of an emissions rebound as a result of the energy efficiency modifications imposed by the ACE rule. Currently, these inefficient and expensive coal-fired plants are not particularly attractive to the power grid–but once they are upgraded, they will be dispatched more frequently, resulting in increased overall hours of operation. So even if their average hourly emissions decrease or stay the same, their overall cumulative emissions are likely to increase (as confirmed in a recent Resources for the Future study). Normally this expected emission increase would require pre-construction environmental review and the installation of air pollution controls to offset the expected increase.

In a comprehensive article just published in Environmental Law News expanding on my initial Legal Planet post, I outline why the Trump EPA’s NSR reform proposal is legally indefensible–and should serve as a cautionary warning to environmental advocates to beware of other returns to failed Bush-era reform attempts to hollow out the Clean Air Act.

Back in the mid-2000s when the Bush EPA first attempted to change NSR’s applicability from cumulative emissions to hourly emission rate, they had apparently gotten the idea from the very industry they were supposed to be regulating. Between 1988 and 2000, Duke Energy repaired or replaced 29 boilers at 8 coal-fired power plants in North Carolina, extending the useful life of pre-Clean Air Act equipment first installed between 1940 and 1975, and allowing the power plants to increase hours of operation. Duke Energy did not go through pre-construction environmental review before making these modifications, arguing the replacements did not increase the hourly emission rate and therefore were not modifications subject to NSR. Under the Clinton administration, the United States filed an enforcement action against Duke Energy for its failure to apply for permits. After the 2000 election, the Bush administration (thanks to environmental nonprofit intervenors) continued the litigation, eventually taking Duke Energy all the way to the Supreme Court. Justice Souter rejected Duke Energy’s arguments and found that EPA’s regulatory approach looking to cumulative, annual emissions rather than the hourly emission rate was perfectly reasonable under the Clean Air Act. Just over a month later, the Bush EPA would issue its notice of proposed rulemaking to change its interpretation to match Duke Energy’s. (This Bush-era reform effort was never finalized before the Obama administration took office.) One common denominator between the 2007 reform efforts, Duke Energy, and the current reform proposal? Current Assistant Administrator for EPA’s Office of Air and Radiation Bill Wehrum, a key player in the Bush EPA and a former attorney for Duke Energy and other energy industry clients.

As an expert agency, the EPA is of course entitled to change its interpretation of the statutes it is charged with administering. But that interpretation must be a reasonable one. And as I explain in more detail in the full article, the Trump EPA’s proposed interpretation is clearly contrary to Congressional intent in the Clean Air Act. In striking down other Bush-era NSR reform efforts in the early 2000s, the DC Circuit ruled in a series of cases that the Clean Air Act unambiguously requires application of NSR any time a source is expected to increase emissions, and that “EPA lacks authority to create an exemption from NSR by administrative rule.” Here, the Trump EPA attempts to do just that: create an impermissible carve-out for the coal industry through a tortured reading of the Clean Air Act that contravenes the very heart of NSR. I’ll let the 2006 DC Circuit explain:

Given Congress’s goal in adopting the 1977 amendments of establishing a balance between economic and environmental interests, [citations], it is hardly “farfetched,” [citation], for Congress to have intended NSR to apply to any type of physical change that increases emissions. In this context, there is no reason the usual tools of statutory construction should not apply and hence no reason why “any” should not mean “any.” Indeed, EPA’s interpretation would produce a “strange,” if not an “indeterminate,” result: a law intended to limit increases in air pollution would allow sources operating below applicable emission limits to increase significantly the pollution they emit without government review.

(New York v. EPA, 443 F.3d 880, 885-90 (2006)). If you’re craving a deeper dive into the legal analysis, I encourage you to read my full article.

Originally expected to be finalized in March, it’s now unclear when the final ACE rule will be issued given there appears to be no end in sight to the federal government shutdown. But it’s certain that if the NSR reform proposal remains in the final rule, it will be promptly challenged by the same environmental groups that fought the Bush-era NSR reform efforts the first time.

Reader Comments