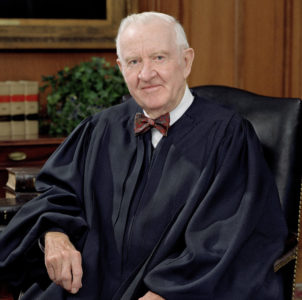

Justice John Paul Stevens, 1920-2019, Was An Environmental Hero

He was frequently the environmental voice of the Court

Justice John Paul Stevens was a giant figure in the history of the United States Supreme Court. He should also be remembered as the Court’s greatest modern environmental voice. He authored the opinion in two of the most significant environmental cases of the last twenty years and the dissent in a third.

Justice John Paul Stevens was a giant figure in the history of the United States Supreme Court. He should also be remembered as the Court’s greatest modern environmental voice. He authored the opinion in two of the most significant environmental cases of the last twenty years and the dissent in a third.

Three times in the last 18 years, Professors Jim Salzman and J.B. Ruhl have surveyed environmental law professors and lawyers about the most significant environmental cases in the modern era. They just published the results of their most recent survey – conducted in 2018/19, in an article called American Idols (behind a paywall). Three of the top cases, by near unanimous vote, are Massachusetts v. EPA, Chevron v. NRDC, and Rapanos v. United States. All three were named in the 2009 survey as well.

Mass v. EPA is, of course, the case that held that the Clean Air Act covers greenhouse gases and that the State of Massachusetts could sue to force EPA to determine whether carbon pollution coming out of the tailpipes of cars “endangers public health and welfare.” Justice Stevens wrote the majority opinion. Chevron v. NRDC – a challenge to a Clean Air Act rule — held that if a statute is ambiguous, courts should defer to expert agency interpretations of the statute as long as the agency interpretation is reasonable. Justice Stevens wrote the majority opinion. And Rapanos v. U.S. involved the extent of federal jurisdiction over wetlands. Justice Stevens wrote a powerful dissent to Justice Antonin Scalia’s opinion for the Court, though in the end it was Justice Anthony Kennedy’s concurring opinion that established the precedent lower courts have, largely, applied. Justice Stevens would have deferred to EPA’s relatively expansive interpretation of which wetlands the Clean Water Act covers as a reasonable interpretation of the statute.

Dan Farber wrote this helpful post nine years ago (pre-Legal Planet!) about Justice Stevens’ environmental jurisprudence, adding to the top three a number of others: the Benzene decision, for which he wrote a plurality opinion striking down an OSHA rule setting a workplace standard for Benzene, Babbit v. Sweet Home, upholding the Secretary of the Interior’s interpretation of “harm” under the Endangered Species Act to include significant habitat modification, and several others. Dan’s conclusion about Justice Steven’s philosophy is that Stevens had “a strong preference for democracy and agency expertise over judicial policymaking.” He was not, in Dan’s view, necessarily driven to protect the most environmentally protective position, which is certainly true in both the Benzene and Chevron cases.

But Justice Stevens’ more recent environmental jurisprudence, especially Mass v. EPA and his Rapanos plurality opinion, may have reflected a more aggressively environmentalist view, especially as environmental issues have become more and more polarized. Certainly his opinion in Mass v. EPA, in which he crafted the standing portion to garner Justice Kennedy’s vote and to grant standing to the state, and in which he found a non-discretionary duty on the part of EPA to determine whether carbon pollution endangers public health and welfare, is not about agency expertise and democratic democracy. Professor Jon Cannon, the former EPA General Counsel who wrote a foundational memo arguing that the Clean Air Act covered greenhouse gases and the author of an important book on environmental cases in the Supreme Court, said that Mass v. EPA “reflects sympathy with environmentalist beliefs and values to an extent rarely, if ever, seen in the Court’s environmental cases.” Justice Stevens is the Justice who expressed those environmentalist beliefs and values. Stevens embraced the science of climate change and directed EPA to do something about it. Whatever his underlying motivation, Justice Stevens should be remembered for his significant environmental legacy. Whether that legacy will withstand the Roberts Court — Mass v. EPA, Chevron and Rapanos could all be at risk — remains to be seen.

Reader Comments