The Impacts of Explicitly Racist Land Use Practices Persist in California Communities. Is It Time for State Intervention?

A new report from the Frank G. Wells Environmental Law Clinic explores the relationship between California’s long history of racism in land use and environmental permitting. It also shows the path forward.

The Frank G. Wells Environmental Law Clinic and the Leadership Counsel for Justice and Accountability have released a new report, Concentrated Overburden, that explores the connection between California’s history of racialized land use practices and environmental injustice throughout the state. The report provides recommendations for actions by the California Legislature to soften the impacts of past discrimination in how––and under what circumstances––local governments permit polluting land uses in overburdened communities.

In making the case for its suggested land use reforms, the report details the broad scope of local land use authority under the California constitution, how this authority has been––and sometimes still is––deployed in ways that advance segregation along race and class lines throughout California, and how this segregation has facilitated and exacerbated environmental injustice.

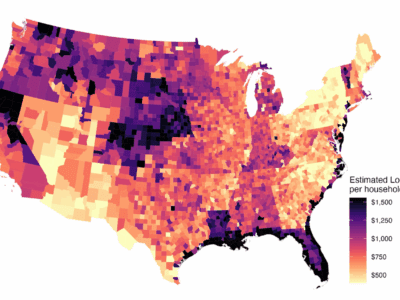

Of course, local land use authority is not the only cause of California neighborhoods’ division along race and class lines. Federal policies like redlining––the Federal Housing Administration’s use of lending guidelines to favor White neighborhoods with lower pollution burdens in grading mortgage risk––co-located Black and Brown communities near unsafe, toxic, and noxious land uses. And the private use of race-restrictive covenants, backed by homeowners’ associations and state courts, further entrenched racial segregation in neighborhoods throughout California.

All the same, land use authority was a critical and synergistic tool underpinning these exclusionary policies. For instance, redlining policies gave growth-oriented local governments an incentive to use their zoning authority to create White residential enclaves, as those areas could receive more favorable lending terms for residential development. This created the added incentive for residents of these White enclaves to protect their investment through racist deed restrictions, many of which are still written into the deeds of thousands of properties throughout the state.

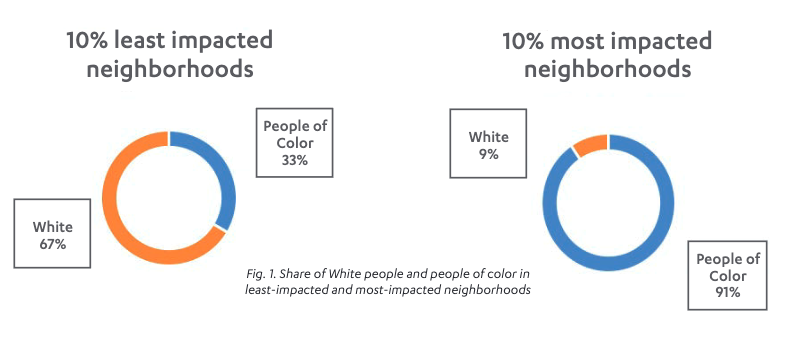

While we are now more than 80 years removed from the inclusion of redlining standards in federal guidelines, and more than 60 years removed from the passage of California’s Fair Employment and Housing Act, pollution burdens are still distributed along lines of race and income. For instance, the 10 percent of census tracts with the highest pollution and socioeconomic burden are 91 percent People of Color, per CalEnviroScreen, while the 10 percent of census tracts with the lowest pollution burden are only 33 percent People of Color. This is true, in part, because many municipalities and counties exercised their local zoning and land use authority to preserve a status quo built on the foundational injustices of redlining and restrictive covenants.

Research conducted by students in the Frank G. Wells Environmental Law Clinic set out to uncover how deep these injustices run. A survey of 30 local jurisdictions across the state, performed by the Clinic, found that local governments frequently zone for and permit harmful land uses in poorer, non-White areas. In many cases, localities permit potentially hazardous land uses by-right, evading traditional environmental review and community engagement processes. The Clinic also found that almost all local permitting processes––when they require more than ministerial box-checking––do little to ensure that they alert potentially-impacted communities of proposed projects. The student researchers found that local notice provisions typically do not apply to tenants, nor do they require project proponents or local officials to translate notices into prevailing local languages other than English. The effect of these provisions is that notice laws are often so limited as to apply only to landowners within a few hundred feet of the project.

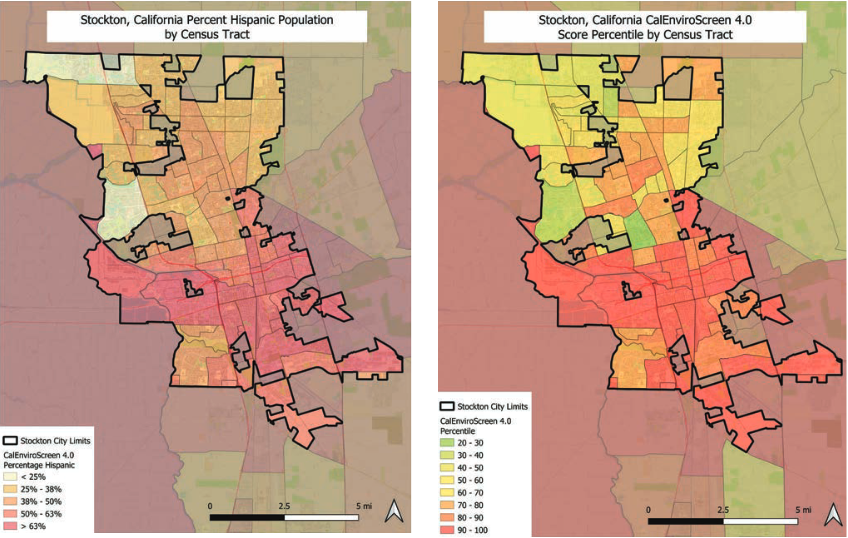

To better understand the historical roots of these entrenched practices and disparities––and how state-level reforms may carve a path toward more equitable land use policies across the state––the report considers three case studies of cities across the state: Stockton, Huntington Park, and Fresno. Each of these case studies examines the policies that have shaped the demographic makeup of each city and funneled polluting land uses and communities of color into the same neighborhoods. Each case study includes several vignettes highlighting specific projects in each jurisdiction. Through these vignettes, several major themes emerge.

First, local governments often allow hazardous or noxious land uses in environmental justice communities “by right,” meaning that they receive automatic approval as long as they meet basic requirements. This limits the avenues for community members to voice opposition to projects in their neighborhoods and the power of local governments to stop proposed projects in overburdened communities. For example, the zoning designation for the Port of Stockton allows almost any industrial use without a permit, blocking any input from the majority-Hispanic and low-income neighborhoods near the port.

Second, even where local decisionmakers have discretionary permitting authority over locally unwanted land uses, they often resist policies that would critically examine and change the practices that have traditionally placed locally unwanted land uses in low-income communities of color. Consequently, decisionmakers may continue to permit harmful projects in environmental justice communities on the basis that similar projects have been allowed there in the past. This  can be seen in the fight for fair zoning in the West Fresno, where Fresno’s City Council is partially reversing a community-centered plan that would have phased out industrial uses in the area.

can be seen in the fight for fair zoning in the West Fresno, where Fresno’s City Council is partially reversing a community-centered plan that would have phased out industrial uses in the area.

Third, in the uncommon cases where local agencies impose meaningful permit conditions on facilities in environmental justice communities, those agencies are often unwilling to take action to enforce permit conditions, even in the face of organized community opposition. Enforcement failures like these allowed a meat-rendering plant in Fresno to operate without required permits for decades, until a community-led campaign shut it down.

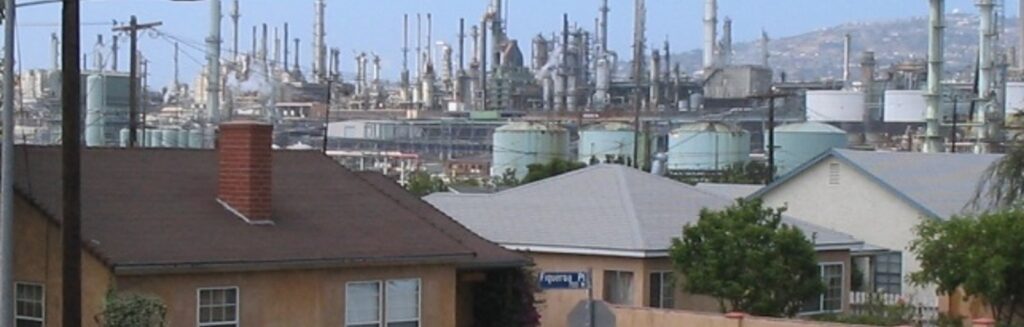

Finally, extra-jurisdictional hazards further limit recourse for members of disadvantaged unincorporated communities or cities with small geographic footprints. Residents of these communities have little voice in permitting processes and are less likely to be engaged in the broader land use planning processes of other jurisdictions. As a corollary, local decision-makers are far less politically accountable to residents living outside of their jurisdiction, allowing these decision-makers to impose negative externalities on neighboring communities. This lack of cross-border accountability—combined with a failure of enforcement on the state and local levels—was behind the infamous Exide battery-recycling plant that put over 100,000 residents at risk in Huntington Park and nearby cities.

The Legislature has already demonstrated its understanding of the critical link between environmental justice and land use planning and siting decisions. Legislation such as AB 617 (C. Garcia), SB 1000 (Leyva), and SB 1137 (Gonzalez) are prominent examples of the State’s interest in rectifying past and ongoing harms borne by disadvantaged communities due to land use decisions. However, to build upon and strengthen these efforts, the report concludes with key recommendations designed to respond to the specific shortcomings in local land use policies detailed therein. Among the thirteen recommendations the report puts forward are:

- Prohibit by-right approval of the siting or expansion of polluting land uses near disadvantaged communities, and require project proponents to obtain a discretionary permit, such as a conditional use permit, to ensure that projects undergo individualized environmental review. Require local governments to make special findings that a project will not exacerbate environmental degradation or worsen public health outcomes when approving the project.

- Require cities and counties to provide meaningful public notice and opportunities for community members to provide input in response to proposals to site or expand polluting land uses near disadvantaged communities. Notice should be translated into locally-spoken languages and provided to residents promptly after localities receive applications for proposed developments or expansions and prior to key opportunities for community input, such as community meetings and public hearings. The State should also require that cities, counties, and project proponents hold community meetings within disadvantaged communities near proposed project sites and hold public hearings outside of normal working hours when elected officials vote on the proposal. Require cities and counties to incorporate and meaningfully consider resident input.

- Enhance public notice and scoping meeting requirements under CEQA for projects that propose the siting and expansion of polluting land uses in overburdened communities to meaningfully solicit input from community residents about projects’ potential environmental impacts along with mitigation measures and project alternatives which would avoid or reduce those impacts. Align CEQA public engagement requirements with enhanced public process requirements.

- Strengthen conditions and oversight on the use of state funding by local governments to incentivize land use practices which support community engagement and public health in overburdened communities and penalize actions that exclude residents from land use decision-making processes, reinforce or exacerbate over-concentrations of polluting land uses, and fail to correct legal violations of polluting land uses that jeopardize the health, safety, and well-being of residents of overburdened communities. Establish screening procedures to prevent the advancement of state infrastructure projects, such as freeway expansions, and other state actions and expenditures which would perpetuate and contribute to unequal pollution burdens and unjust land use patterns impacting disadvantaged communities.

- Require facilities near disadvantaged communities burdened by high levels of localized air pollution to reduce toxic air emissions and air emissions exposures of vulnerable residents according to more stringent air emissions thresholds and expedited timelines than otherwise required under the Clean Air Act and other applicable laws.

Read the full report from Leadership Counsel and the Clinic here.

Reader Comments

4 Replies to “The Impacts of Explicitly Racist Land Use Practices Persist in California Communities. Is It Time for State Intervention?”

Comments are closed.

No, these are not “explicitly racist.” That would mean they are intentionally racist, but they are not. Racial terms are not used in these rules. Perhaps you mean “disparate impact.”

It’s certainly true that some of the modern policies we describe in this brief are implicitly, rather than explicitly, racist. But some are not: for example, Richard Drury recounts in the Environmental Law Reporter a meeting in which the representative from the company that owned “La Montaña,” the concrete-recycling facility that polluted Huntington Park for years, “suggested” that the predominantly Hispanic community members resisting the facility “were probably not even in the country legally” (38 ELR News & Analysis 10338). Freeway siting is an example from a different perspective: at least some of those decisions are understood to be racially motivated, and those policies are physically present in cities all over the state. (Pete Buttigieg’s interview with theGrio is probably the most clearcut acknowledgement of this: https://thegrio.com/2021/04/06/pete-buttigieg-racism-us-infrastructure/.) And from a broader perspective, the land-use decisions that were made in the early and mid-twentieth century are effectively still in place, because the same land uses predominate, backed by most of the same legal regimes.

That said, we have changed the post title here to clarify the point we’re trying to make.

It seems like it would be easier to move people than to move a port. Maybe the problem was letting people be housed in industrial zones? Maybe that’s what needs to stop.

Easier, perhaps–but that’s part of the problem: the easiest path is the one that continues the racist and classist pattern of land-use policy. A core part of our argument, as I see it, is that the human cost of these policies outweighs any convenience they may bring. In any case, there’s plenty that can be done to reduce the impacts of existing facilities like the Port of Stockton—starting with deciding not to add new sources of pollution.

As for the collocating of residential and industrial zones, it’s almost never as simple as allowing homes to be built in industrial areas. The problems we highlight in the brief are mostly the opposite of that: new or expanded industrial uses allowed where people already live. And industrial and residential uses often grow up together, particularly when racialized political or economic patterns create areas where it is easy and cheap to build, and displaced demand from areas where it is hard to build flow in.