Our Mental Models of Climate Change

How did “Collective Action” turn into “No Action”?

In discussions of how to cut global greenhouse-gas emissions, one of the first things you usually hear (often the very first) is that cutting emissions is a global collective-action problem. To wit: it’s crazy for California (or the United States) to cut unilaterally, because it only works if everyone does it. Or more sharply, we can cut all we want but it won’t make any difference because what about China? (Leave aside the inaccurate claim that China is doing nothing to cut emissions – in fact it’s doing plenty, including the announcement of a nationwide cap-and-trade system last week.)

In discussions of how to cut global greenhouse-gas emissions, one of the first things you usually hear (often the very first) is that cutting emissions is a global collective-action problem. To wit: it’s crazy for California (or the United States) to cut unilaterally, because it only works if everyone does it. Or more sharply, we can cut all we want but it won’t make any difference because what about China? (Leave aside the inaccurate claim that China is doing nothing to cut emissions – in fact it’s doing plenty, including the announcement of a nationwide cap-and-trade system last week.)

Just in the past three weeks, we have seen these arguments advanced in debates about the attempt in California’s 2030 and 2050 emission targets into legislation; in denunciations of the Obama Administration’s Climate Protection Plan; and in over-heated reactions to Pope Francis’s statements on climate change.

The idea that cutting emissions is, fundamentally, a global collective-action problem is everywhere in policy argument and academic commentary.

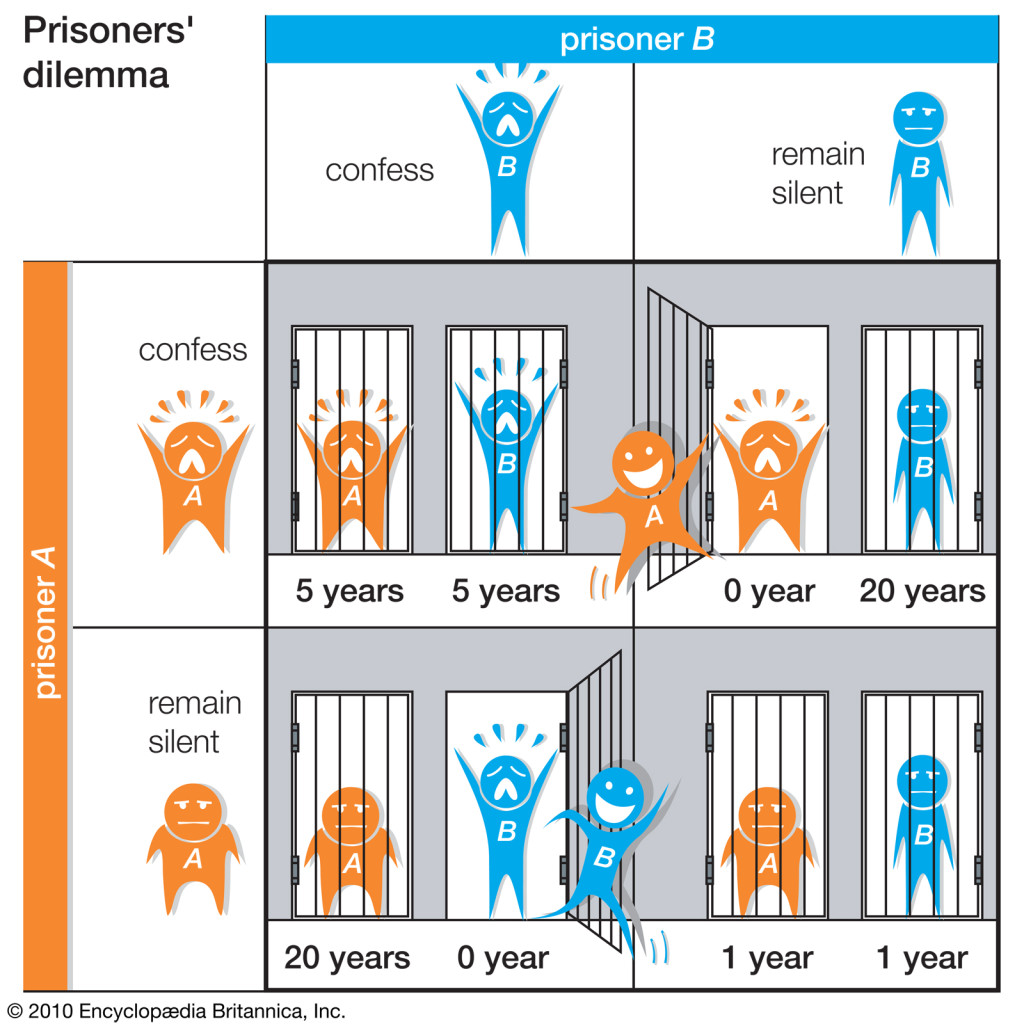

It has a long history, dating back to the earliest academic commentary on the issue in the 1980s – much of which asked, is cutting emissions a Prisoner’s Dilemma (the toughest form of collective-action problem, in which individuals acting co-operatively are always harmed, no matter what others do), or might it be some other, less malign form of collective-action (e.g., the alternative games “Chicken” or “Assurance,” for those into game theory), in which there are conditions, depending on what others are doing, where cooperative choices can be individually advantageous. This way of talking, and thinking, about climate-change mitigation has powerful rhetorical advantage: it has tons of academic respectability, and also resonates directly with a crude strategic logic everyone recognizes from the schoolyard. I won’t unless you do. You go first. He did it too, it’s his fault.

But over the now pretty long history of arguing about cutting greenhouse-gas emissions, two weird things have happened.

First, talk about collective action has grown more extreme, and has increasingly been taken over by those who oppose any attempt at action to solve the problem. In the toughest collective-action problems, it is true that everyone has to move together and be careful to verify that others are doing their part, since acting alone is costly. But the notion that no one can do anything until everyone is ready to move in lock-step, with meticulous verification of every step, presumes an extreme form of collective-action reasoning, which has shifted from appropriate caution about the need for global participation (eventually) to an insurmountable argument of futility.

Second, there is more and more evidence that the fit of standard collective-action reasoning to the real problem of cutting global emissions is substantially weaker than has been imagined. The few jurisdictions that have been taking leadership positions in cutting emissions don’t appear to be suffering any harm from it, at least none that is observable relative to the noise of short-term economic fluctuations. And the strongest opponents of action have opposed not just cutting their own emissions, but also others trying to cut their emissions.

I started thinking about this a few months ago, in some discussions aimed at producing policy briefs proposing new approaches to climate action, convened by the Centre for International Governance Innovation (CIGI) in Canada.

I realized that if you consider the possibility that collective-action issues might be less dominant in the climate-change problem – not absent of course, but just not the single, over-ridingly important thing – then the problem looks completely different, as do the main directions for effective near-term action. For one thing, there is more space to get action started with significant leading steps by single jurisdictions or coalitions, such as we are now seeing. Viewing the issue this way re-casts the problem of getting to the required deep global cuts as a multi-stage process, in which serious leadership by subsets of actors is feasible, with these actors then controlling the agenda to build incentives for others to follow.

Moreover, if you back off from seeing everything through the collective-action lens, a couple of other big challenges come into clearer focus, which suggest different priorities for early action.

In my policy brief, I propose that the two biggest of these challenges are the problem of delayed benefits and the problem of concentrated opponents. Thinking about these problems implies substantially different strategic guidance for early climate action than thinking about collective action first and foremost.

Delayed benefits: Actions today to cut emissions of long-lived gases like CO2 only slow climate change with a time-lag of a few decades. Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, made a similar point in a speech Tuesday on climate-change risks to the insurance and financial sectors, arguing that the long time-horizons of climate change both magnify the risks and weaken the ability of financial markets to respond. If you think about designing early actions to mitigate this challenge, you pay more attention to the inter-temporal character of action rather than its immediate collaborative aspects. You think about constructing packages of actions that combine progress on long-lived emissions with other actions that bring immediate benefits. You think about constructing adaptive structures for inter-temporal decisions that combine strong commitment to a climate-protection goal with means to adjust the details by which you pursue the goal as knowledge and capabilities advance.

Concentrated opponents: This is the big one. Estimates of the costs of cutting emissions to slow and eventually stop climate change are persistently small overall (assuming a long transition and sensible policies), but these costs are unequally borne. They fall most strongly on the industries and places that are getting rents from the present fossil-fuel based global energy economy, and these folks have mightily and effectively resisted every step toward shifting the economy away from those sources. If you think about designing early actions to mitigate this challenge, you pay more attention to strategic moves to overcome the political power of these opponents – e.g., by concentrating early actions in jurisdictions where they are less powerful, by designing policies to shift the burden onto them remotely, and by moves to divide them.

I develop these ideas in more detail in the CIGI policy brief, which is available here.

Reader Comments

One Reply to “Our Mental Models of Climate Change”

Comments are closed.

Ted said;

“…….strategic moves to overcome the political power of these opponents – e.g., by concentrating early actions in jurisdictions where they are less powerful, by designing policies to shift the burden onto them remotely, and by moves to divide them…..”

Dear Ted,

Why not simply rely on valid persuasive arguments to convince America that your ideas are righteous? This is the strategy that we (your opponents) have adopted and you must admit that thus far we have done very well in obstructing the Clean Power Plan. Our good work will increase – we shall eventually bury the CPP in the trash heap of wasted government scams.