The Uneasy Case for NIMBYism

A Growing Class Conflict Lurks Underneath the Land Use Debate

Paul Krugman is turning his attention to housing affordability, and the results as usual are salutary. When discussing the skyrocketing cost of housing in New York City, he observes:

There’s still room to build, even in New York, especially upward. Yet while there is something of a building boom in the city, it’s far smaller than the soaring prices warrant, mainly because land use restrictions are in the way.

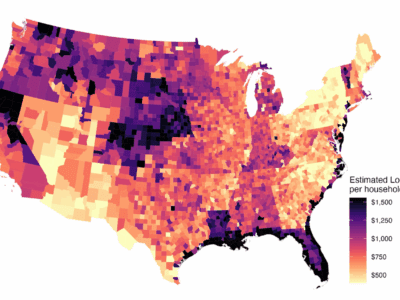

And this is part of a broader national story. As Jason Furman, the chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers, recently pointed out, national housing prices have risen much faster than construction costs since the 1990s, and land-use restrictions are the most likely culprit. Yes, this is an issue on which you don’t have to be a conservative to believe that we have too much regulation.

I often tell my students the same thing: if you are a conservative looking for the most over-regulated sector of the American economy, you can’t do any better than local land use.

But Randy Shaw, the editor of Beyond Chron and the director of San Francisco’s Tenderloin Housing Clinic, is having none of it. On the contrary, he argues:

Krugman’s blaming of land use restrictions for rising housing costs in urban America is . . . misplaced. Restrictions that limit rental housing and keep tenants out of neighborhoods and entire cities are clearly a cause of the nation’s housing crisis, but such policies are not what ails New York City or other major urban areas.

To the contrary, New York City is a case study for how loosening land use restrictions promotes gentrification. That’s because allowing thirty-story condo towers in formerly low-rise neighborhoods like Williamsburg rapidly expedited the gentrification process. This new housing, like most of that built after the Bloomberg Administration’s rapid rezoning of 35% of the city, did not serve “the 90%” and instead contributed to the city’s rising homelessness and increased displacement.

Land use restrictions are actually among the most critical tools for slowing or stopping gentrification.

Shaw has something of a point, although less of one than he thinks. His example is well-taken: removing rent controls and height restrictions from a low-rise building and letting the developer do whatever it wants will in fact lead to less affordability, not more. But that is a bad comparison for two reasons.

First, there is an easy way around this dilemma: simply lift the restrictions while guaranteeing a certain number of affordable units in the new building. One could call it a density bonus or an inclusionary ordinance, but in either case, it would represent a substantial deregulation of current rules. In fact, one could probably get more affordable units in such a deal because the landowner would be happy to include more such units in exchange for greater density. The real reason why many — although probably not Shaw — support lower density in this case is NIMBYism, not a concern for affordability.

Second, the notion of “affordability” is equivocal here. Many people often use “affordability” colloquially, and it usually means something along the lines of, “Can a typical middle-class family afford a house or apartment in this jurisdiction?” Looking at this way, Krugman is clearly right: the best way to bring down the overall cost of housing is to increase its supply, and partially deregulating land use (with the caveats mentioned above) is the best way for a local government to do that.

But Shaw means “affordable” in a different, and more technical sense: he is alluding to housing for low-income people, defined as living between 40% to 80% of the median income in a metropolitan region, or perhaps even very-low-income people (between 0% and 40%). If one is focused on this population, then increasing supply will not necessarily help. Low and very low income people lack housing because they don’t have enough money, and barring a really massive increase, there pretty much will always be a shortage. That is why Shaw emphasizes, rightly, that “maintaining economic diversity requires significantly more state and federal housing funds.”

Note that there is an important connection with more traditional environmental concerns: as a friend of mine once said of life in cities, “someone has to serve the arugula.” That’s a blunt way of saying that if we consign low income people to exurbs, that will increase VMT. So good climate policy also requires economic diversity at some level.

Sometimes these two types of affordability conflict, as with AB 744 (about which I wrote a couple of weeks ago), and this can create dangerous politics. Providers of affordable housing for low and very low income people opposed relaxing parking requirements near transit stops because they wanted to be able to offer such relief as a carrot to developers in exchange for affordable units. But blocking meaningful parking reform will increase the cost overall, to the detriment of the middle class. This opposition remains a terrible mistake in my view: progressive politics works very poorly when it pits the middle class against the poor, and as I just argued above (as well as in the previous post), it doesn’t need to. Whatever one’s view of class conflict, it makes no sense for progressives to eat their own.

Reader Comments