Getting Lost In The Woods?

New Study From India Points to Dangers From Forestry Sector Emissions Trading

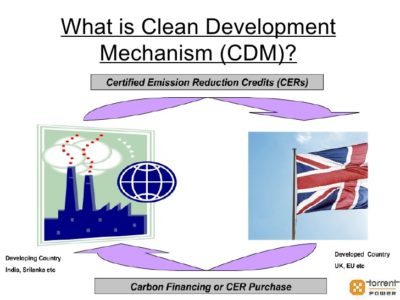

Despite the Trump Administration’s dedication to melting the planet, the rest of the world is gamely pushing ahead with implementing the Paris Accord, and that means programs like United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+) and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The two are linked, because a big part of CDM involves Afforestation and Reforestation – thus, “CDM A/R.”

Despite the Trump Administration’s dedication to melting the planet, the rest of the world is gamely pushing ahead with implementing the Paris Accord, and that means programs like United Nations Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (REDD+) and the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The two are linked, because a big part of CDM involves Afforestation and Reforestation – thus, “CDM A/R.”

But there is a big problem here, at least when it comes to India, according to the Indian Institute of Management’s Ashish Aggrawal in the recent Economic and Political Weekly:

Carbon forestry projects such as REDD+, A/R CDM and the Green India Mission are based on the neo-liberal principles of privatization, commoditisation, and marketisation. These market-oriented tools abstract forests from their sociocultural and ecological contexts and reduce their value for carbon forestry. These projects promote plantations of fast-growing species and undermine local knowledge and institutions. The available empirical evidence on the carbon forestry projects indicates that these have an impact on the rights and livelihoods of forest-dependent communities adversely. Hence, it is imperative to critically analyse them before scaling them up.

I admit that I hate the term “neo-liberalism.” It basically serves as placeholder for anything the writer doesn’t like. As political scientist Seth Masket once tweeted, “one day I will teach a seminar called ‘Neoliberalism’; everyone will just come in and scream about things we hate.” Aggrawal here defines it more precisely, but the value of this piece is not the theoretical stuff at the beginning, which is fairly standard, but rather his application of it.

Aggrawal is critiquing the application of emissions trading to the forestry. The economic logic of emissions trading is straightforward: allow emitters whose reductions would be expensive to pay cheaper emissions-reducers to do it. In the forestry sector, this appears to have the same logic. Suppose a developer wants to develop a parcel of land with a forest on it. No problem: buy another piece of land, and grow new trees on it. So the emissions reductions you lose from development are made up for – and perhaps more – by growing new trees somewhere else that is less expensive. Done. Perfectly sensible.

Not so fast, says Aggrawal. He argues that our knowledge of carbon sinks is more primitive than is often claimed, so we actually don’t know with precision how much carbon a new, plantation forest will get out of the atmosphere. In the meantime, development has destroyed actual ecosystems – not to mention the local communities that have long depended upon those ecosystems. Moreover, the supposed carbon benefits of the new forests depends upon monitoring and enforcement institutions, and those too are weak, or even nonexistent. India claims that so-called “Joint Forest Management Committees” will do this work, but they could be co-opted by more powerful forces. Who will guard the guardians.

I suppose I liked this piece particularly because Aggrawal doesn’t dismiss the logic out of hand: rather, he is asking the hard questions that must be answered if market-based mechanisms like REDD+ and CDM for forestry will actually work. It’s dreary at the end of an article, and really something of a cliché, to “call for further research,” but it is necessary here to ensure that the cure doesn’t become worse than the disease, and to leap at new institutions only to find a barren, melted planet.

Reader Comments

3 Replies to “Getting Lost In The Woods?”

Comments are closed.

There’s another problem. The mechanism seems designed around carbon sustainability. If it works, it will attain this, at a cost in biodiversity, aesthetics and community. But we now face the necessity of massive carbon removal later this century. It’s fairly clear that current global mean temperatures (+1 deg C from pre-industrial) are risky, the unavoidable +1.5 degrees will be bad, and +2 degrees disastrous (eg with no coral reefs left, according to the IPCC). About the only shovel-ready technologies we have for carbon sequestration are tied to land use: conservation agriculture and reafforestation. So carbon balance is not enough. There will need to be a mechanism for funding large-scale net reafforestation such as recycling a carbon tax, but all tree-felling for timber paper and firewood will need to pay it. I can’t see a place for wood pellet electric power stations like Drax.

Agree completely; there is no such thing as a free lunch, and we are going to have to pay for it in things like higher prices for wood and paper products (or at least some of them). I think you could do it if you said that for every tree you fell, you have to replace double the carbon sink. But you still have the problems that Aggrawal talks about.

Paper, if buried, actually can be a carbon sequestration mechanism, though not as long term or as friendly as we would like. A cynical engineer I once worked with used to note that engineering is often a choice between bad things; “What flavor $$$$ do you want to eat?”.

Perhaps instead of recycling some kinds of waste, we could make them into a slurry and pump them into old coal mines, oil reservoirs and …? (This might help prevent parts of Northern Pennsylvania from subsiding as well.) The carbon in them would be available once we make ourselves extinct and the intelligent cockroaches that succeed us need fossil fuels themselves.