Deforestation and the Climate Crisis in a Time of Pandemic

Despite the pandemic-induced global economic contraction, deforestation increased last year, with significant increases in the destruction of primary tropical forests.

Earlier this week, the World Resources Institute released its first assessment of global forest loss for 2020, offering a chance to take stock of what happened to the world’s forests during the pandemic. The news is not good. Despite a shrinking global economy, deforestation increased around the world in 2020.

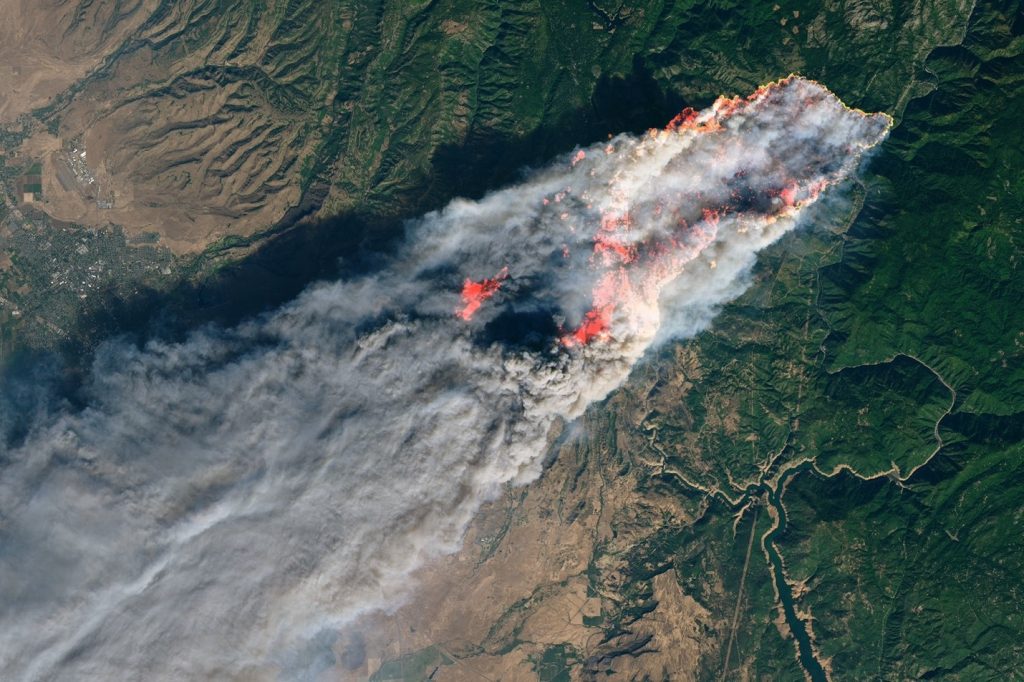

In temperate regions, some of the most significant forest loss occurred because of unprecedented fires. Here in California, more than 4 million acres burned—roughly 4% of the state’s total land area, shattering previous records and emitting more than 112 million metric tons of CO2e. That’s slightly more than 25% of the 2020 GHG emission target for the entire state: 431 million metric tons, which does not include land-based emissions. It’s also almost double the emissions from the state’s electric power sector in 2018 and about two-thirds of the 2018 emissions from the state’s transportation sector (2018 is the latest year for which the California Air Resources Board is reporting data under its GHG inventory). Needless to say, California’s progress on climate action, not to mention its air quality and overall livability, are directly threatened by these forest fires.

In Australia, fires in late 2019 and early 2020 burned an astonishing 21% of the country’s temperate broadleaf and mixed forest biome area, driving a 9-fold year-over-year increase in deforestation in that country. In Russia, unprecedented wildfires in Siberia burned some 26 million hectares (65 million acres), which is about the size of the state of Colorado.

Years of neglect and inattention to the ongoing forest crisis and its central role in the larger climate crisis are now being amplified in truly terrifying ways as climate disruption accelerates. It is past time to recognize that forests and land use must be at the center of the climate emergency.

Quick shout out: Wildfire Law is the subject of Berkeley Law’s Ecology Law Quarterly 2021 symposium on April 16. Details are available here.

The most worrisome development with respect to global forest loss, however, continues to be in the tropics. Despite the significant contraction of global economic activity during the pandemic, loss of primary tropical forests increased by roughly 12% compared to 2019—rising to a total of 4.2 million hectares, an area the size of the Netherlands. According to the WRI assessment, “[t]he resulting carbon emissions from this primary forest loss (2.64 Gt CO2) are equivalent to the annual emissions of 570 million cars, more than double the number of cars on the road in the United States.”

Most of this deforestation occurred in Brazil, with the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Bolivia, Indonesia, and Peru rounding out the top 5. In Brazil, primary forest loss increased by 25% compared to 2019 with more than three times the area lost compared to the next highest country (DRC). Clearing for pasture and soy as well as fires were the main proximate causes. As noted in previous blog posts, (see here and here), the Bolsonaro government has directly contributed to the problem by weakening environmental laws, dramatically reducing enforcement, and actively promoting the development of protected areas and indigenous territories. In fact, despite the global outcry about the forest fires in Brazil during 2019, the 2020 fire season was worse, with some fires now burning inside moist tropical forests, rather than on the edges of disturbed forests. The huge tropical forest wetland ecosystem that drains the southern Amazon, the Pantanal, burned on an epic scale this past year. This increasing vulnerability of tropical forests to drought and fire surely stands as one of the most frightening implications of accelerating climate disruption.

There were a few bright spots in the data for 2020. Last year was the first year that Indonesia was not in the top 3 countries for tropical deforestation, demonstrating ongoing and sustained progress in that country in reducing deforestation for the fourth year in a row. But that progress is fragile, as the Government of Indonesia has recently adopted a controversial new Omnibus Law that weakens labor and environmental protections and reduces government regulations in an effort to promote more foreign investment. All of which is taking place against a backdrop of massive increases in unemployment and rising precarity for millions of people across Indonesia in the wake of the Pandemic. Pressures to kick start the economy in a world of rising palm oil prices will surely increase the threats to Indonesia’s forests.

As the world emerges from a global pandemic caused by a novel zoonotic coronavirus, the importance of protecting tropical forests should be self-evident. But the prospects on the ground are daunting. National governments across the tropics are struggling to restore economic growth in the face of severe fiscal constraints and an uncertain political environment. At the same time, state and provincial governments are being forced to cut budgets and staffing for forests and climate activities. In some jurisdictions, work on the forest and climate agenda has virtually stopped. While this may all be necessary and understandable in the midst of the pandemic, the question is what it means for budgets and staffing going forward and whether key civil servants who have been so crucial to the forests and climate agenda will lose their jobs or leave the government.

Civil society partners that have supported this agenda for many years are also facing a much less secure future. This could undermine already fragile partnerships and reduce pressures for more government accountability. Networks and relationships that have taken decades to establish and that provide much of the glue that holds this agenda together are at risk of disintegrating in a matter of months.

Most important, all of the structural vulnerabilities that make climate change so dangerous for poor, front-line communities all over the world are being compounded and amplified by Coronavirus across the tropics, with devastating effects on indigenous and local communities throughout the Amazon and beyond.

While it is too early to tell, the political impacts of the pandemic on the forests and climate agenda in tropical forest regions could be far-reaching. Some politicians will surely lose their bids for reelection, and some may even be removed from office. For those who remain, Covid 19 may push them to look inwards as they tend to ongoing public health and economic crises. Pressure to deliver on jobs and economic growth will be extreme, and could further fuel populist anger toward conservation and forest protection efforts.

The Biden Administration’s re-engagement with the international climate agenda and its attention to deforestation in the Amazon as part of that is a welcome and much needed departure from the previous administration. Expectations are rising for substantial public and private sector commitments of billions of dollars to compensate national and subnational efforts to reduce emissions from tropical deforestation under various “pay for performance” schemes. In all of this, it is critical that such support not be reserved only for a handful of high performing jurisdictions. A substantial amount must also be directed to and tailored in a manner that meets governments and their civil society partners where they are and reflects their priorities and needs rather than those of international climate policy elites. The risk is that the donor community and the growing number of private sector actors interested in offsetting their emissions will focus only on the demand side—that is, they will proceed (as they have in the past) on the assumption that if there is a substantial enough market demand signal for emissions reductions this will all somehow trickle down to change behavior on the ground. That is naïve and will almost certainly fail if it is not combined with the vital work of supporting fragile processes underway in tropical frontiers all over the world to fight corruption, land grabbing, violence, and entrenched poverty. All the money in the world will not solve the problem if we ignore the complex reality on the ground.

Reader Comments