Centering Public Health at the UN Climate Talks

Guest Contributor Meleana Chun-Moy reflects on COP28 and the growing recognition of the intersection between the climate crisis and human health.

The climate crisis is a public health crisis, and it finally seems global leaders have recognized that fact. With the backdrop of the first-ever Health Day at the annual UN climate conference, air quality in Dubai soared, as PM2.5 pollution reached 155 micrograms per cubic unit. The World Health Organization states the annual average concentrations of PM2.5 should not exceed five µg/m3. Air pollution is harmful to human health as it exacerbates and causes an increase in health issues, like respiratory illnesses. The poor air quality—juxtaposed with the COP28 climate negotiations underway—made the need for action abundantly clear.

I attended the climate conference as part of the UCLA Law delegation. When I heard that COP28 would be the first year that health had ever been showcased, I thought someone misspoke. Indeed, it was a first. In 27 years of previous climate conferences, there was no central discussion of health and the impacts of climate change. To me, environmental law and climate policy are about people, protecting people, and advocating alongside those disproportionately affected by climate change. While everything is connected to our ecosystems, and our oceans and rainforests are essential, people are most impacted and vital. It is hard for me to fathom how negotiators and delegates convened for decades without viewing the climate crisis through the lens of people and health. This year, over 40 million doctors, nurses, health ministers, and other health professionals came together to call for robust action to phase out fossil fuels and work towards a healthier future for those most affected. By contrast, this year there was an unprecedented number of fossil fuel lobbyists in attendance. More than ever before.

Climate change affects everyone. Yet, it disproportionately affects communities of color, small island nations, people with disabilities, Indigenous people, and already vulnerable communities. Rising temperatures impact agriculture, farmers, and our food systems. Fossil fuel emissions lead to poor air quality and increased air pollution which in turn are harmful to health. Women and children, especially girls, are more susceptible to these climate consequences, and women bear the brunt of it. In many communities, women take on more unpaid responsibilities, including child rearing, managing households, caring for the elderly, and obtaining food and water. With the climate crisis, women must travel further for supplies which leaves them with less time for paid work and more potential risk to their personal safety.

Climate change intersects with physical health in myriad ways. During the conference, 2023 was declared the hottest year on record. Wildfires, floods, tropical storms, heavy rainfall, heatwaves, malnutrition, and droughts are increasing in frequency, intensity, and scale. Food systems and waterborne illnesses increase with extreme weather events. Previously contained diseases such as malaria, cholera, and dengue are now rampant as mosquitoes thrive in warm waters. Fossil fuel emissions cause respiratory conditions, lung cancer, stroke, and heart disease. Air pollution, coupled with extreme heat, disproportionately affects pregnant people and babies. According to a 2021 study by Harvard University, the University of Birmingham, the University of Leicester, and University College London, more than eight million people died from fossil fuel pollution in 2018. Stated differently, one in five deaths can be attributed to fuel emissions.

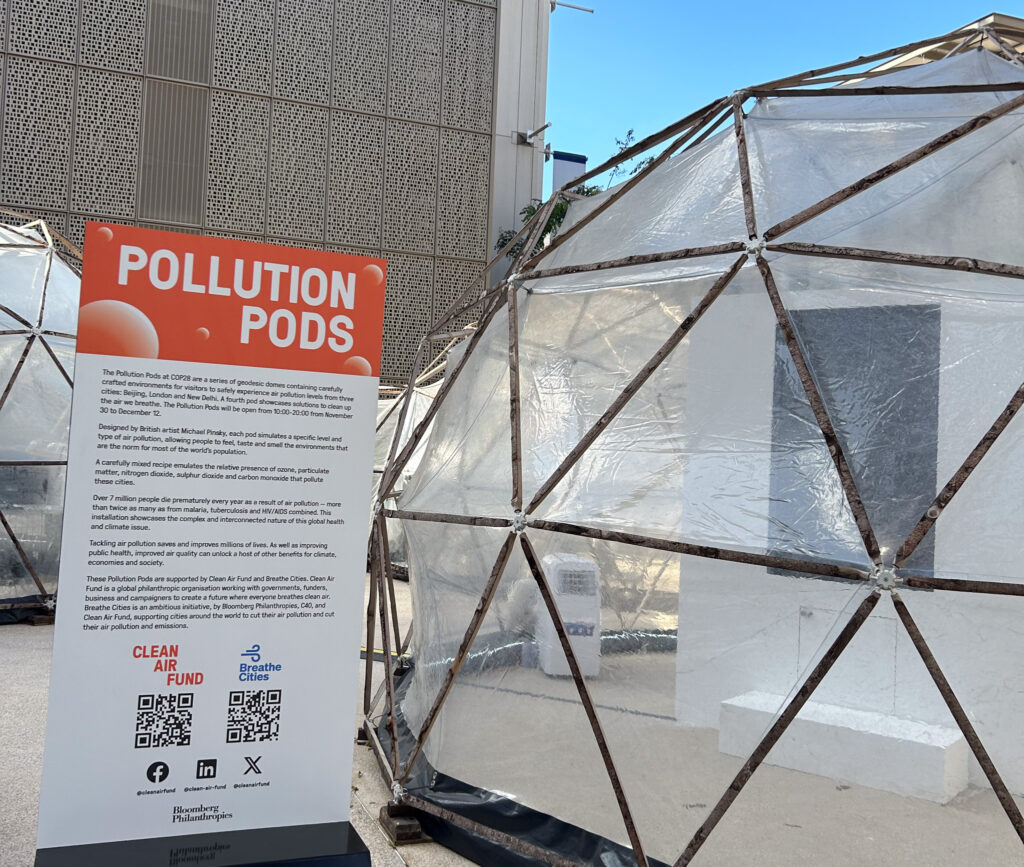

As I left a session in the Blue Zone, I stumbled upon one of the most impactful exhibits at COP28: Clean Air Fund’s Pollution Pods, created by Michael Pinsky. The exhibit consisted of several geodesic domes that mimicked the air and noise pollution in major cities: London, Delhi, and Beijing. The domes safely immersed visitors in the sights (or lack thereof due to poor visibility), smells, tastes and sounds of each city. Each pod replicated different pollutants such as particulate matter, ozone, nitrogen dioxide, carbon monoxide, and sulfur dioxide. Having worked with environmental justice communities in Los Angeles, I thought I understood air pollution. I was wrong.

Moving through each of these pods, I could feel how difficult it was to breathe and see even a few feet in front of me. At the exhibit’s end, I entered a “clean” pod to experience how air should be and learn more about solutions to combat air pollution. The contrast was stark. In the clean pod, everything was visible; you could take a deep breath and not feel lightheaded. The experience made me grateful that in comparison to these cities, the air in many parts of Los Angeles is not as bad, though there is still lots of work to do.

Although it is often left out of the discussion, climate change impacts mental health too. One COP28 session I attended was about how climate change and mental health are interconnected. Children today and future generations must deal with the consequences of previous generations not acting to combat climate change.

Eco-anxiety is high among many people, but particularly youth under age 24. People feel disillusioned and discouraged by the state of our world. It is a heavy feeling that young people deal with daily. A new study shows that by 2030, some $47 billion will be spent on mental health costs of the climate crisis. Due to the mental health burden of climate hazards, air pollution, and the like, mental health costs will increase to over $537 billion by 2050.

As drought becomes increasingly common, many farmers feel despair and depression. Some are dying by suicide. There is insufficient time between each acute weather event to cope and recover. It is great that there are drought-resistant crops, but who is going to plant them if the farmers cannot get out of bed? One of the speakers told the story of a farmer in Kenya. After seeing his friends pass away and feeling defeated, he is now a mental health therapist helping his community. It goes to show that resilience is no longer just a matter of bouncing back from each climate catastrophe, but resilience requires transformation of communities on the front line. There is a need for connection, including local communities in decision-making, using traditional wisdom, and connecting policy and research to mental health.

Much has been made of the shortcomings of COP28 in addressing one of the main causes of climate change: fossil fuels. Despite this, I also saw one of the successes of COP28 in fully recognizing one of the main effects of climate change: the physical and mental health emergencies. No future climate conference will be able to ignore the connection again.

Meleana Chun-Moy is a J.D. candidate (‘24) at UCLA Law.

Reader Comments