Guest Bloggers Rob Verchick and Matt Shudtz: Law Professors from Every Coast Ask SCOTUS to Weigh in on Louisiana Coastal Wetlands Case

Professors Argue Fifth Circuit Decision Upsets Federal/State Court Balance, Will Prevent States from Relying on Their Own Laws to Protect Important Natural Resources

Last month, more than two dozen law professors from around the country filed a friend-of-the-court brief with the U.S. Supreme Court, urging a fresh look at a lower court decision with sweeping implications for the balance of power between states and the federal government. The issue is vital to Louisiana because it affects whether oil and gas companies can be held liable for decades of damage they have done to the state’s coastal wetlands.

The case is ambitious, to say the least. The Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority—East is a small government agency that manages a complex system of levees, floodwalls, gates, pumps, retention systems, and more to keep Louisiana’s residents safe from flooding. The levee authority does this even while sea levels rise and the spongy wetlands that might aid its work disappear at a rate measured in acres per hour.

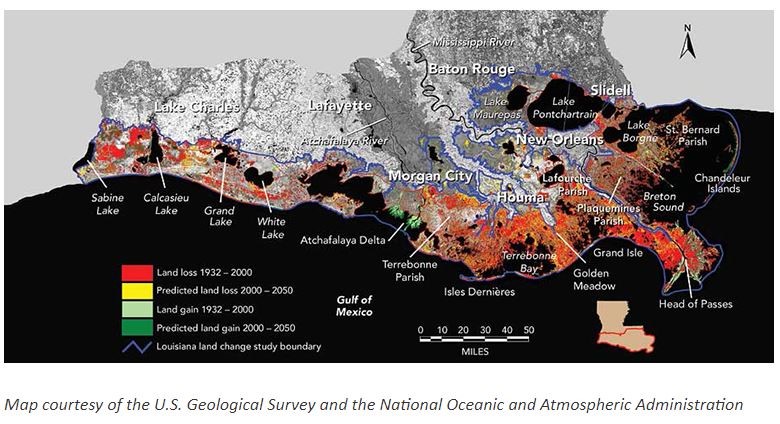

In the lawsuit, the levee authority is up against 87 oil and gas companies that have contributed significantly to the degradation and loss of those coastal wetlands. Estimates vary, but the industry itself admits that its 50,000 wells, 10,000 miles of pipelines, and vast network of canals caused more than a third of the coastal wetlands loss that has to be seen to be truly appreciated. ProPublica illustrates it best here:

The courtroom is just one front in the battle between the levee authority and multinational corporate giants. Along the way, former Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal did his best to derail the case, challenging the authority’s powers and even trying to stack its membership. Those attempts failed and the lawsuit sailed ahead. But it hit a jurisdictional snag along the way which now threatens the whole case.

The issue concerns whether plaintiffs have the right to have their claims against the oil and gas companies—all of which arise under Louisiana law—by a state, rather than a federal court.

In its case against the companies, the levee authority asserted state claims under nuisance, negligence, breach of contract, and other theories. It also argued that Louisiana’s own public trust doctrine imposes a duty on all state agencies to protect the natural resources it holds in trust for all Louisianans. In 2004, the Louisiana Supreme Court said that disappearing coastal lands are precisely the kind of resources that deserve strong protection. Because much of the case depends on how unreasonable the companies’ actions were, the levee board took pains to document every wrongful action in every canal that they could find. To illustrate the range of the companies’ wrongful activities, it referred to three federal laws that they likely also violated.

The oil and gas companies, looking for a sympathetic court, argued that the reference to federal violations makes the case better suited for a federal judge. Judge Nannette Jolivette Brown of the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana agreed. And so did the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals when the levee board appealed the decision.

But the levee authority—and now more than two dozen law professors—say the courts got it wrong. The reason has to do with what is called “arising under” jurisdiction. When a plaintiff files a case in a state court, the defendants can request that it be transferred to a federal court if the ultimate issues in the case can be said to “arise under” federal law. According to a U.S. Supreme Court case called, Grable & Sons Metal Products v. Darue Engineering & Manufacturing, that should happen only where the state claims “necessarily” raise a substantial federal issue and only where resolving the claims would not disturb the careful balance between state and federal judicial responsibilities.

In this case, it’s plausible a state court might have ruled in the levee authorities’ favor without considering federal law at all. The extent to which state law holds companies liable for coastal damage like this is still being tested in state courts. No one knows exactly what the limit is.

But instead of leaving it to a state court to develop the law, Judge Brown short-stopped the process and opined—without citing any case directly on point—that in no circumstances could Louisiana law, on its own, hold these oil and gas companies liable for the damage of thousands of acres of wetlands. If the state law can’t stand on its own, she reasoned, federal law must take center stage. The whole thing seems a little backwards. To get to the federal issue, you have to first resolve a question of state law—a question, incidentally, that no state court has ever had the chance to address.

Now the levee authority is asking the Supreme Court to weigh in, and the law professors who have signed the brief—including three Legal Planet regular contributors and one of the authors of this blog post—are encouraging it to do so. They argue that the lower courts misinterpreted Supreme Court precedent on the balance of state and federal judicial responsibilities, and note that leaving the lower courts’ decisions in place will prevent states from relying on their own laws to protect their important natural resources.

For more, check out the amicus brief here. To learn more about the public trust doctrine, visit CPR’s webpage on the subject. (And note also the recent analysis, discussed here on Legal Planet, of California’s public trust doctrine and coastal land use.)

Rob Verchick is the Gauthier-St. Martin Chair in Environmental Law at Loyola University New Orleans and President of the Center for Progressive Reform.

Matt Shudtz is the Executive Director of the Center for Progressive Reform.

Reader Comments

One Reply to “Guest Bloggers Rob Verchick and Matt Shudtz: Law Professors from Every Coast Ask SCOTUS to Weigh in on Louisiana Coastal Wetlands Case”

Comments are closed.

This case is limited to circumstances where the remedy (e.g., backfilling of federal levee system) and standard of care (e.g., compliance with federal dredging permits) are determined by federal law. If only a state law cause of action is pled, and a remedy is sought and available under state law, then this case would not provide precedential authority to remove or dismiss an action brought under state law.