July Fourth at Mt. Rushmore: What about the “unalienable rights” of the Lakota?

In the limbo game of the 45th presidency: no matter how far the bar descends, Trump clears it by going under. Just two weeks after political furor over a planned Juneteenth support rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma—site of the 1921 Race Massacre, in which white mobs killed up to 300 Black people in 48 hours, and burned or looted some 1,500 homes—Trump found a way to go still lower. He celebrated Independence Day in the Black Hills of South Dakota, on land properly occupied by and sacred to the Oglala Lakota Nation.

The Black Hills became federal property in 1877 only by virtue of the United States’s breach of treaty promises (that the area would remain Lakota land) as soon as gold was discovered. The U.S. Army subsequently wrested the area from Native occupants by the ruthless military incursions that Black Elk so devastatingly recounted to John Neihardt. In the late 1920s, the multi-year carving of the Mount Rushmore Memorial began. (The 19th Century territorial dispute remains unresolved; a monetary judgment in favor of the Lakota still sits in trust, while the Tribe seeks re-possession of the Black Hills in addition to compensation for their long dispossession.)

In spending July 4th in the Black Hills, Trump was implicitly celebrating an original nation-building sin that predates even slavery: invader-colonists’ treatment of Native Americans, and the lands key to Native sustenance and beliefs. The irony of choosing a landscape exemplifying the worst horrors of colonialism to celebrate . . . the rejection of colonialism . . . is surpassed only by the further aggression in the specific choice of Mount Rushmore. The granite mass into which visages of four powerful white men are chiseled is, according to Lakota, sacred ground— a part of the spiritual mother, and the site from which (culturally central) bison come. Given the gap between the celebrated leaders’ stated ideal of human equality and the poverty of values the national Memorial in fact embodies, it’s no wonder the late American Indian Movement activist Russell Means called Mount Rushmore “the shrine of hypocrisy.”

As if this were not enough: Native American leaders expressed grave concern that Trump’s celebration was putting tribal members’ health at risk from the coronavirus, given their communities’ background medical conditions and poorly funded healthcare system. In Trump’s deliberate indifference to Native Americans’ particular susceptibility to contagious disease, one needn’t think hard to see historical analogies to smallpox as de facto colonial policy.

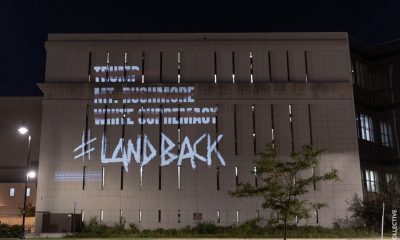

What should the National Park Service do with Mount Rushmore? The existing carvings, and the artworks’ official Memorial status, have been controversial for years. In a sign of the changing times, however, where a petition at Change.org eight years ago to replace the presidents’ faces with those of Native American heroes garnered only 11 supporters total, a similarly motivated one launched two weeks ago (which instead calls for removing the existing portraits) already has nearly 700. Most significant: the indigenous-led NDN Collective—whose members protested Trump’s July 4th presence, sustained arrests, and now have a bail and legal defense fund to deal with the back-end consequences of their activism—has called for the closure of the Memorial and the return of the land.

Consistent with the teachings of our times, the Collective emphasizes that the disposition of Mount Rushmore should not be for the Department of the Interior or any instrumentality of white colonialism (including, even, a Change.org petition) to decide. As the NDN Collective urges, beyond closing the Memorial as a unit of the national park system, the federal government should simply “return the land back to the Lakota people whose land it is for them to decide what to do with it moving forward.”

Implausible as this proposition may at first sound, there is precedent for returning a national park unit to an indigenous people for dramatic re-interpretation and culturally appropriate management. Aboriginal management of Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park in Australia’s Northern Territory—the tourist attraction formerly known as “Ayer’s Rock”—is a particularly poignant example. There, Aboriginal reconception of the park’s meaning and mission has created a fertile marriage of eco-storytelling and cultural-historical storytelling, as exemplified by expansive and inspiring ranger-led activities. Given that Uluru-Kata Tjuta is federally designated protected land centered on a dramatic rock formation integral to Native creation stories, it is no great leap to imagine a similar interpretive trajectory for Mount Rushmore once renamed (perhaps to include “Paha Sapa,” the Lakotan name for the Black Hills).

Enlarging the frame: What should we do with Independence Day? Although our current president was by force of narcissistic will able to ram through a July 4th event in a venue that pointedly revives memories of historic injustices perpetrated against America’s First Nations, the days of such Trumpian political fireworks may be numbered. It is indeed almost easy—in the strange hopefulness of the present—to imagine a scenario in which our nation cures two wrongs with one right, and proclaims Juneteenth rather than July 4th our day of national celebration. Now that would warrant some pyrotechnics.

Reader Comments

2 Replies to “July Fourth at Mt. Rushmore: What about the “unalienable rights” of the Lakota?”

Comments are closed.

This is very interesting, You are a very professional

blogger. I’ve joined your feed and sit up for in search of extra of your great post.

Also, I’ve shared your website in my social networks

Thank you for this very kind comment. A nice start to the week!