Guest Blogger Cliff Villa: Es FEMA El Problema? Hurricane Maria and the Slow Road to Recovery in Puerto Rico

Strolling west on Calle Loiza from the Ocean Park neighborhood of San Juan, Puerto Rico, you could miss the devastation wrought by Hurricane Maria last September. Here in early May 2018, runners and walkers lap the track at Parque Barbosa while middle-aged men try to keep pace with younger guys on the sheltered basketball court. And yet, a chunk of roof over that basketball court is missing and half of the evacuation route sign nearby seems to have been ripped away by winds. Further along Calle Loiza, window signs announce store re-openings (Abierto Ya) and at night the bars and restaurants fill up and emit just enough glow to navigate the uneven sidewalks outside. In the light of day, electricity here – supposedly now reaching 98% of the island – seems improbable, with power poles leaning grimly over streets and power lines dangling like a kelp forest over the sidewalks. All of it seems waiting for the next hurricane – even a Category 1, even a bit of extra wind and rain – to sigh and plunge the island back into darkness.

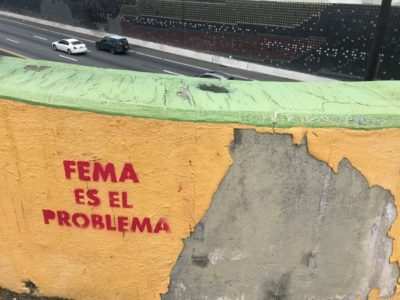

For a sense of how we got here, you can find solid reporting on Puerto Rico and Hurricane Maria from the New York Times, Politico, or any number of real news outlets. But here in San Juan, among the universal graffiti forms and the distinctive toasters (yes, toasters) of street artist Bik Ismo, there is one bold answer stenciled on the freeway overpass and tagged on the side of buildings along Calle Loiza: FEMA ES EL PROBLEMA.

On my first day in San Juan, I was ready to believe it. Ten days later, after conversations across the island and a view into the inner sanctum of the FEMA Joint Field Office, I was compelled to reconsider.

Readers of this space may be informed by history and culture, accustomed to conflict, attuned to nuance. And yet, don’t we, as lawyers and legal scholars, still want someone to blame when things go wrong? Those of us who follow disasters were only too happy to have “Heckuva Job Brownie,” the hapless FEMA Administrator under George W. Bush, to blame for the Government’s anemic response to Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The Deepwater Horizon oil spill in 2010 gave us British Petroleum and whining CEO Tony (“I Want My Life Back!”) Hayward. Hurricane Harvey showcased Houston’s notorious rejection of land use planning. So who gets the credit now, in post-Maria Puerto Rico, for the longest blackout in U.S. history, for the unfathomable pain and suffering experienced by 3.4 million U.S. citizens for weeks and months on end, for the families left with a daily challenge of finding safe drinking water, for the uncountable loss of life, and hope?

We could blame the President of course, distracted by a feud with the NFL for six days after Maria made a Category 5 hit on Puerto Rico on September 20, 2017. We could blame a ponderous Commonwealth government with 141 agencies and overlapping authorities. We could blame the infamous corruption of local officials on the island. We could blame an island culture that promoted infrastructure construction over maintenance. We could blame economic misfortunes, poor management, and crushing public debt of $74 billion followed by debilitating austerity measures. We could blame all these things, while also pointing fingers at FEMA, and many people on the island do.

Diana, my first Uber driver on the island, told me that FEMA required a $500 certification of damage to her apartment in order for her to receive $200 in assistance for repairs. Brenda, Uber driver, 4th grade teacher, and new mom, explained her frustration with FEMA like this: Imagine two cars with worn-out brakes crashing into each other; FEMA will pay to repair the cars to their state before the crash, complete with another set of worn-out brakes, thus ensuring the crash will happen again.

The illogic made sense to me in a way. After all, it wasn’t FEMA’s job to go around handing out new cars with new brakes. But at the same time, I wondered if the analogy was true. Would FEMA really spend billions of dollars ($10 billion so far, with another $49 billion anticipated) just to put Puerto Rico right back into as precarious a position as existed before Maria? In fact, FEMA Administrator Brock Long, appearing before Congress on March 15, 2018, testified to pretty much the opposite. He stated:

… [T]hanks to action taken by Congress, FEMA has new authorities given to us in the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018…. For example, in Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, FEMA may provide Public Assistance funding for critical services to replace or restore systems to industry standards without restrictions based on their pre-disaster conditions.

If you review the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018, you will find this new authority buried in Section 20601 along with many other new provisions yet to be discovered. So maybe Brenda’s car-brakes analogy was wrong, maybe FEMA indeed recognized the illogic of which she complained. I imagine FEMA must have advocated for the change in the law, and was now busy solving problems that few of us could even comprehend. As an Uber driver, 4th grade teacher, and new mom, Brenda could hardly be faulted for not reading the 250-page budget bill carefully.

People who do follow FEMA rules and changes include many committed and creative lawyers on the island and mainland working for academic institutions and nonprofit organizations. At the University of Puerto Rico School of Law, I met with law school faculty, including Dean Vivian Neptune Rivera, and a host of attorneys engaged in providing legal services to the survivors of Hurricane Maria. From attorneys on the frontlines who provide direct legal services to individuals at FEMA Disaster Relief Centers (DRC), I heard many thoughtful critiques of FEMA’s performance on the Maria response.

Most of these critiques concerned FEMA funding for home repairs under the Individuals and Households Program (IHP) of Stafford Act Section 408. There were early complaints about FEMA assistance forms in English that could not be read or understood by the Spanish-speaking residents of the island. There were complaints about lack of training, with some FEMA inspectors making assessments of structural integrity that were well beyond their area of expertise. Perhaps the most common complaint concerned the meaning of an “owner-occupied” residence, complicated by the loss of title documents in the hurricane and the even greater challenge of the “informal” system of property ownership on the island, which may involve properties handed down for generations without recorded documents. Encouragingly, each of these complaints may already be finding solutions. For example, according to Gabriela Camacho, one of the attorneys staffing the DRC, the problem of “informal” ownership may be resolved through use of affidavits attesting to the history of ownership and occupancy, with a model affidavit to be developed for a more efficient process.

From the Disaster Relief Center in Canóvanas to the FEMA Joint Field Office (JFO) in the San Juan suburb of Guaynabo takes about 45 minutes with traffic, but it feels a world away. The JFO is central command for FEMA on the island. Housed in a generic glass office building, the JFO inside is simply breathtaking: all movement and energy, some 2,000 workers and work stations equipped with computers, phones, and pump-bottles of hand sanitizer. Arranged like spokes in a wheel, connected work tables spiral away from a central hub, supporting a massive organization aligned along 12 sectors including Energy, Water, Housing, Education, Transportation, and Natural & Cultural Resources.

Up a spiral staircase is the FEMA “C” suite, where I meet Tito Hernandez, Deputy Federal Coordinating Officer (FCO), the No. 2 guy in charge of a FEMA organization with more than 4,000 people on the island today. Tito’s Executive Assistant announces my arrival and our interview begins promptly as scheduled at 1:15 pm.

If you could dream up someone to lead a massive FEMA response to a major disaster in Puerto Rico, what qualities would you want? Someone with depth of experience, of course, maybe 210 prior deployments. Someone wicked smart, with a capacity for numbers and details, but also a broad vision and dedication to the overall mission. Someone able to acknowledge problems – and committed to solving them. And in Puerto Rico, let’s get someone from Puerto Rico, someone who knows both the language and the culture, and whose own family lives there, securing the ultimate stake in the success of the mission. That person is Tito.

“This is the catastrophic disaster for FEMA,” he says, dispensing with chitchat. FEMA is always preparing for the Cascadia Subduction Zone event, the 9.0 mega-quake in the Pacific Northwest. FEMA plans for the next big hurricane along the Atlantic Seaboard. But Maria was different, a non-CONUS event where nothing could be trucked in and every airport and seaport was shut down on Day 1. And FEMA resources were already stretched thin immediately following Hurricanes Harvey and Irma. Tito sketches a map of the island, demonstrates wind speeds and direction as Maria tore through the heart of the island. He rattles off stats: 18,000 personnel deployed at the peak, 1.1 million meals served per day, 67 hospitals (all of them) shut down initially, two mobile hospitals treating 40,000 patients, 140 helicopters making over 1,000 food drops into remote locations, total FEMA commitment of $60 billion, plus $18 billion from HUD, plus more from other agencies. Over the next five to ten years, 1500 schools will be reduced to 750, reflecting reduced demands due to out-migration from the island. Old public housing will be closed, and both closed schools and closed public housing will be returned to open space. The electrical grids will be rebuilt with a mix of energy sources, including solar and wind (although both remain vulnerable to high winds) and tidal power.

On FEMA assistance to private individuals (Stafford Act Sec. 408) and public entities (Stafford Act Sec. 428), Tito is brimming with more big ideas. One of the most frustrating elements of FEMA assistance to individuals is the statutory cap of $25,000 (now $33,000) set by Stafford Act Sec. 428(h)(1). Imagine if your own home was destroyed by a hurricane. How far would $33,000 get you towards rebuilding? You would have insurance of course, but you may find it covers damage only from wind and not water. However, taking a broad view of FEMA’s authority, Tito talks about combining Sec. 428 funds with other funding programs, including FEMA’s Shelter-In-Place program and the Permanent Housing Construction program, potentially making available combined funds up to $125,000 per household. That could make all the difference between a home and homelessness.

Before and after talking with Tito, I spoke with other senior FEMA officials about their work on Maria. These are some hard-core field agents, people who gave up permanent residences and simply live from one disaster deployment to the next, no more than 51 weeks in any one place. Among these hardened troops, no one had ever seen anything like Maria. Words like “horrific” from federal officials may not instill comfort, but they were there to see it and I was not. Pursuing one more lingering question, I finally asked why FEMA had not seen Maria coming and “pre-positioned” resources on the island before it made landfall. The short answer: FEMA did. In fact, FEMA had a contingent of people in a warehouse in San Juan on the day Maria made landfall. The FEMA warehouse was breached by the hurricane winds and rain, and had to be evacuated like so many other buildings across the island.

Seven months after landfall, talk of Maria on the island continues to stir strong emotions. But one of those emotions is gratitude. Francisco and Illia, new friends in Cabo Rojo on the other side of the island, talked of the FEMA teams in their hotel every morning, planning out their 16-hour days, for days and weeks on end. My Airbnb hosts in San Juan, Sol and her husband Gianluca, offered fairly the same. Echoing comments from across the island, Sol spoke of Maria as a “blessing in disguise” for Puerto Rico, the best chance she has seen for rebuilding both the economy and infrastructure of the island. Anyone with means is buying their own generator now and no one seems fixed on assigning blame for Maria. With June already at hand next month, there is simply too much left to do to prepare for the next hurricane season.

Es FEMA el problema? Quizás, pero también es una parte importante de la solución.

Cliff Villa is an Assistant Professor at the University of New Mexico School of Law, teaching in the areas of environmental law and constitutional law, with particular interests in equal protection, environmental justice, climate change, and disaster response. For 22 years, Cliff worked as an attorney for the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, through EPA offices in Washington, D.C., Denver, Colorado, and Seattle, Washington. Over time, his EPA practice included administrative, civil, and criminal enforcement of federal pollution statutes such as CERCLA and the Clean Air Act. Starting in 2006, he provided on-call legal support for EPA’s emergency response program. He is also a certified liaison officer within the Incident Command System, assisting interagency efforts with disaster readiness and response.

Reader Comments