Making Offsets Transparent

Solve Climate has posted a letter from five state Attorneys General expressing concerns about several provisions of Waxman-Markey (a/k/a ACES). One suggestion they made, in particular, struck me as very persuasive:

[T]he House bill does not require public disclosure of all offset project documentation, including project eligibility applications, monitoring and verification reports for agricultural or forestry offset projects, or disclosure of USDA’s determination of the quantity of GHGs that have been offset by such projects, even though this is required for other types of offsets. In the absence of such disclosure, it is impossible for members of the public, states, and other interested parties to know how credible the offset claims are. The lack of certainty about the integrity of these offsets is also likely to lead them to be valued lower by the market.

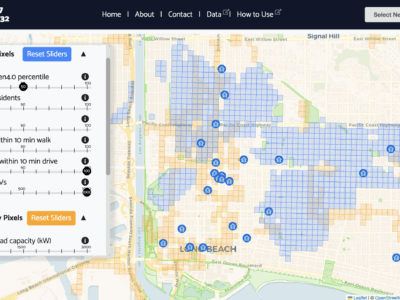

Indeed, I would go further and mandate that the relevant documents be available on-line in a central repository and linked to a GIS (Geographic Information System) so it would be easy to find individual offset projects and track where those projects are taking place. Without this kind of transparency, it’s hard to see how the system can maintain credibility.

Reader Comments

2 Replies to “Making Offsets Transparent”

Comments are closed.

In our work at NRDC, we’ve seen a lot of gaming of the system by entities involved with air pollution offsets under the Clean Air Act. Timely, accurate public disclosure of where such offsets come from and where they are used would be a big step forward.

I agree that offset verification is essential.

Another important point the AGs make has to do with preservation of state authority to undertake.

Regrettably, however, the AGs seem unaware that the Waxman-Markey measure’s proposed trading scheme would nullify, at least in part, the climate benefits of state programs — and that is so even if final Congressional legislation were to retain current formal state authority to operate GHG reduction measures.

This is so because, under the cap & trade scheme, reductions in demand for fossil fuels or FF-derived energy would result in surplus allowances that then are likely to be sold on the market, allowing additional GHG pollution elsewhere.

In theory, W-M allows states to compel entities within their jurisdiction to surrender allowances. But the effect of reduced demand due to state action may be surplus allowances held by entities outside the state undertaking the GHG reduction measure, or else the effect may be to reduce prices overall.

Thus, W-M would raise doubt that state action really would lead to additional reductions beyond the minimum required under the proposed new federal scheme — upending the traditional role the AGs point out has worked well over four decades in which states are able to go beyond the federal minimum in combating pollution.

A solution would be for EPA to restrict allowances nation-wide to account for reductions from state action that would otherwise occur. Unless such an amendment is taken, the effect of W-M would be to nullify the climate effectiveness of state initiatives even without directly preempting the authority of states to enact their own programs.