One Year and Counting

He’s played his cards. Next year, we’ll see how well the other side plays theirs.

In September, Eric Biber and I released a report assessing the state of play in environmental issues 200 days into the Trump Administration, based on an earlier series of blog posts. As we end Trump’s first year, it’s time to bring that assessment up to date. It follows the same outline as the previous report but omits a lot of the detail. I will focus on our predictions at that time and how they’ve borne out since then. But first, some general thoughts about the past year.

The bad news.

Despite some early thought that Trump might moderate his campaign positions on energy and environment, that hasn’t happened. If anything, as he has tied himself more and more to the coal industry, his positions have only hardened. Fortunately, converting those positions into effective policy isn’t just a matter of Trump sending a tweet or picking up the phone and giving an order.

Trump campaigned on opposition to all things environmental and promised exponential growth in fossil fuels. You can’t accuse him of breaking his promises. He said he would repeal Obama’s climate change regulations, and he’s started the machinery for doing so. He said he would repeal the Waters of the United States (WOTUS) rule that expanded protections for wetlands. And his EPA has proposed doing so. He said would pull out of the Paris Climate Agreement, and he has formally announced a decision to do so. He said he would open public lands to more mining and drilling, and he’s doing his best there too. The well-regarded estimate of the social cost of carbon has also been tossed out.

Some things have gone worse than expected. Congress made surprisingly vigorous use of the Congressional Review Act to toss out some of Obama’s last regulations, with more impact on public lands than on pollution or climate. Scott Pruitt, Trump’s appointee to head EPA, has spent most of his time out giving speeches and cultivating industry donors to advance his own political future, while doing his best to destroy the agency he heads. Conflicts of interest are rife in an Administration that seems to be staffed by former (and future) industry lawyers, executives, and lobbyists. In fact, it might be reasonable to say that the absence of conflicts of interest is now an unusual situation. As in other areas, the Administration has refused to pivot to the center in any respect. The NY Times found enforcement levels even below Bush’s: “During the first nine months under Mr. Pruitt’s leadership, the E.P.A. started about 1,900 cases, about one-third fewer than the number under President Barack Obama’s first E.P.A. director and about one-quarter fewer than under President George W. Bush’s over the same time period.” The Administration is also requesting about half as much in the way of remedial actions as Bush, and far, far less than Obama.

Glimmers of hope.

On the positive side, the resistance to Trump has been even stronger than expected. States like California and New York have ramped up their climate change efforts in response to Trump, and they have become more active in the international sphere. Fortunately, Trump’s defection from the Paris Agreement has had no effect on other countries so far — indeed, the two earlier holdouts (Syria and Nicaragua) have joined the agreement. Meanwhile, donations to environmental groups are way up, and lawsuits against the Administration are blossoming.

By the end of Trump’s second year, we’ll know a lot more about how many of Trump’s plans will actually come to fruition. His regulatory rollbacks are mostly still in the rule-making phase. They should be finalized in Year 2, and we’ll start to see how well they’ll fare in court. The 2018 mid-term elections will also be important. If the Democrats manage to retake the House, they’ll be in a good position to protect agency budgets and fight off legislative riders. They’ll also be able to launch some major investigations against Scott Pruitt, Ryan Zinke, and their ilk, which could help restrain some of the worst abuses. In the meantime, the Democrats will have strengthened their positions in state governments, allowing expansion of renewable energy in a dozen or more states. That’s if the mid-terms go in their favor.

But all of that remains to be seen. So, stay tuned for a pivotal year for the environment. In the meantime, here’s where things stand right now.

The state of play.

Legislation. Eric and I considered substantive legislative changes very unlikely although potentially very damaging. So far, there is little sign that anti-environmental bills will be able to move on the Senate side. Appropriation riders remain possible but haven’t been a major factor so far. The one possible exception to our prediction is the reconciliation process, which we considered difficult to use for environmental rollbacks. The Senate tax bill includes a provision opening up ANWR for drilling, which may pass muster under reconciliation procedures since it will generate revenue.

Budget. We viewed this as a likely method of undermining environmental protection. The budget process remains a mess, but so far, the Trump Administration has not succeeded in getting the major cuts to EPA that Trump was seeking. Small cuts will still prove harmful but are not as draconian.

Pollution and Climate Change. We pointed out that regulatory rollbacks would be harder to achieve than some Trump Administration officials seemed to think because of the need to comply with rule-making procedures and assemble sufficiently strong justifications to survive judicial review. The Administration is trying hard to roll back important rules protecting wetlands and limiting carbon emissions, but it remains to be seen how these efforts will fare in court.

Enforcement. Lack of government enforcement is impossible for courts to police. In the environmental area, there’s a backstop method of enforcement whereby citizens and states can bring enforcement actions. So far, we haven’t seen any statistics about what’s happening in this area. But there’s every reason to think this Administration will enforce as little as possible.

Public Lands. One of Trump’s efforts is to eliminate protections of public lands so they can be opened to other uses, especially mining and oil drilling. Although a lot depends on what statutes apply to particular tracts of public land, the executive branch does have discretion in land management. Zinke is certainly trying hard to eliminate protections, but it’s too soon to tell to what extent he’ll succeed.

Executive Orders. Most of Trump’s executive orders were really just instructions to agencies; they didn’t actually have any direct legal effect. We are seeing a couple of exceptions, however. The first is the effort to reduce or eliminate some national monuments through presidential decree. The other is imposition of tariffs on importers of solar panels, which will happen by the end of the month. These are both potentially serious blows to the environment, assuming they stand up in court.

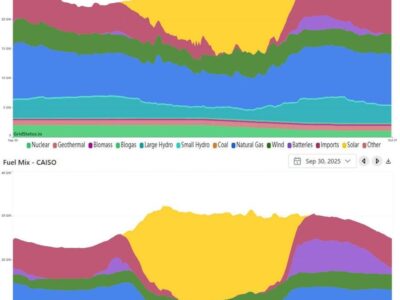

State and Local Action. We viewed actions by state and local governments as the best available way of making environmental progress during the Trump years. If anything, the prospects have only brightened for this activity. Mayors and governors were a strong presence at the Bonn climate talks in November. In addition, Democratic gains in off-year elections in several states have strengthened the hands of environmentalists.

One characteristic of the Trump Administration is a ceaseless stream of controversies and dramas. But generally speaking, the amount of actual legal change has been much more limited, because the system is designed to provide checks on administrative and legislative action.

Reader Comments

2 Replies to “One Year and Counting”

Comments are closed.

Interesting how a civilization devolves to leadership by finger-pointing because our leaders continue to fail to solve the root cause problem documented by historians Will and Ariel Durant back in the 6os:

“When a civilization declines, it is through no mystic limitation of corporate life, but though the failure of its political and intellectual leaders to meet the challenges of change.”

Add to this President Eisenhower’s grave warning in his 1961 Farewell Address to the Nation:

“The prospect of domination of the nation’s scholars by Federal employment, project allocations, and the power of money is ever present – and is gravely to be regarded.”

So today, we now have failures of all branches of government, and all of our institutions to protect our democracy and civilization while increasingly out of control climate changes destroy remaining opportunities to perpetuate an acceptable quality of life for our newest and all future generations.

Even though Berkeley identified a root cause in a 2006 CALIFORNIA alumni magazine cover story “Can We Adapt in Time?” https://alumni.berkeley.edu/california-magazine/september-october-2006-global-warning/can-we-adapt-time

We continue to marginalize this fact of life and continue to finger-point at our increasing peril.

Prof. Farber, the paramount global warming question that still remains unanswered at our increasing peril:

“Can We Adapt in Time?”

Why does the IPCC keep marginalizing this question, along with continuing to fail to heed and act upon Ike’s grave warning on the Power of Money that corrupts far too many scholars to the point where we still fail to produce fusion power plants like Edward Teller advised us to do in the 60s!?