Contentious California Beach Access Case Heads to U.S. Supreme Court

Longstanding Martins Beach Controversy May Well Capture Justices’ Attention

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 2018-19 Term is already shaping up as a big one for environmental law in general and the longstanding tension between private property rights and environmental regulation in particular. The Court has already agreed to hear and decide two cases next Term raising the latter set of issues: one involves the question of how extensively federal regulators can limit development of private property that’s deemed by government to be “critical habitat” for animals listed under the Endangered Species Act; the other concerns whether the Court should renounce some or all of the “ripeness rule” it created in 1985 limiting property owners’ ability to bring “regulatory takings” cases in federal courts. (Those pending cases were profiled in earlier Legal Planet posts found here and here.)

Now the justices are being asked to take up a third, high profile case next Term pitting environmental values against private property rights. That case, Martins Beach 1, LLC v. Surfrider Foundation, Supreme Court No. 17-1198, just so happens to be California’s most controversial and heavily-litigated coastal access case over the past decade. The recently-filed petition for certiorari asks whether efforts by environmental organizations and state government regulators to maintain public access across private lands to the California coast triggers a compensable taking of private property under the U.S. Constitution.

The facts and origins of the Martins Beach controversy have been well-publicized and are by now familiar to many. The relevant facts are set forth succinctly by the California Court of Appeal at the beginning of its decision–Surfrider Foundation v. Martins Beach 1 LLC–from which U.S. Supreme Court review is being sought:

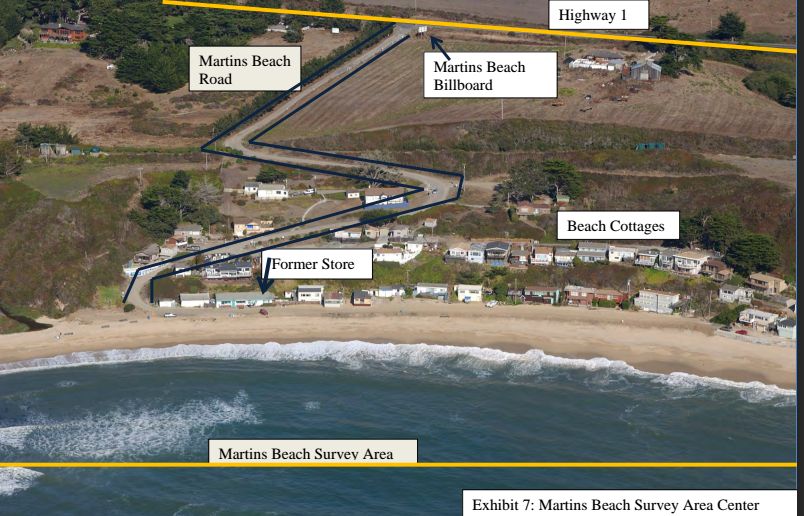

“Nestled in a cove, sheltered on the north and south by high cliffs, Martins Beach lacks lateral land access. The only practical route to Martins Beach is down a road, known as Martins Beach Road, that leads from Highway 1 in San Mateo County to the Beach. [The previous landowner had for years allowed public access through the private road to the beach during daylight hours, charging a small fee to do so. The current landowner] purchased Martins Beach and adjacent land including Martins Beach Road in July 2008…A year or two after purchasing Martins Beach, [the new landowner] closed off the only public access to the coast at that site.”

The property owner’s unilateral closure of access to Martins Beach triggered a political controversy that eventually garnered national media attention. On one side of this public access dispute is coastal property owner Vinod Khosla, a Silicon Valley billionaire who–at least until he unilaterally terminated public access to Martins Beach–was best known as the co-founder of Sun Microsystems. On the other side are public access organizations led by the Surfrider Foundation (which originally filed the litigation) and public agencies including the California Coastal Commission and San Mateo County.

The Surfrider Foundation’s lawsuit, commenced in 2013, is straightforward: it asserts that landowner Khosla could not discontinue previously-afforded public access to Martins Beach unless and until he first obtains a coastal development permit under the California Coastal Act. That’s because, Surfrider argues, Khosla’s actions to close and lock an access gate across Martins Beach Road at its junction with California Highway 1 constitute “development” under the Coastal Act for which a coastal development permit is required. Khosla’s attorneys argued that simply closing the access gate doesn’t qualify as a “development” under the Coastal Act and, even if it did, requiring Khosla to continue providing public access across his land constitutes a “physical taking” of his private property rights under the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The trial court and state Court of Appeal both ruled in favor of Surfrider, agreeing with the organization that Khosla’s unilateral closure of the access route to Martins Beach required a coastal development permit under the Coastal Act. Those courts similarly rejected the landowner’s taking claim, ruling that it was not “ripe” for decision unless and until he first applies for a coastal development permit and the permit is subsequently denied. Finally, the Court of Appeal upheld the trial court injunction requiring Khosla to keep the beach access road open while the state court litigation proceeds on the merits.

(Surfrider’s lawsuit is only of several legal initiatives commenced to keep the Martin’s Beach accessway open. Another NGO, Friends of Martin’s Beach, filed suit against Khosla, arguing that the public has a state constitutional right of access to Martins Beach or, alternatively, that Khosla’s predecessor had permanently dedicated a right of access to the public that Khosla could not revoke. [That case remains pending in the trial court.] Meanwhile, Khosla filed his own preemptive lawsuit against the Coastal Commission and San Mateo County, seeking a court ruling that he was not legally required to maintain public access to Martins Beach. [Khosla’s lawsuit was dismissed by the trial court on procedural grounds.] Both the Coastal Commission and the county have sent Khosla formal letters advising him of the government regulators’ position that the landowner’s unilateral termination of public access to Martins Beach indeed constitutes “development” requiring a coastal development permit under the Coastal Act before public access can be eliminated. And, finally, the California Legislature enacted legislation in 2014 authorizing the California State Lands Commission to acquire a right-of-way or easement across Khosla’s property to Martins Beach, by eminent domain if necessary. [So far, the Lands Commission has not initiated legal action to secure that accessway.])

After the California Supreme Court declined to review the Court of Appeal’s decision in favor of Surfrider, Khosla last month filed his petition for certiorari with the U.S. Supreme Court, urging the High Court to take up the case on its merits. His petition presents two questions for Supreme Court review: 1) whether the state court-issued preliminary injunction requiring the access road to remain open constitutes a per se physical taking of Khosla’s property for which compensation is required under the Takings Clause; and 2) whether requiring him to apply for a permit from the Coastal Commission before closing the Martins Beach access road similarly violates the Takings Clause.

Khosla’s petition has both some key strengths and certain glaring weaknesses. Perhaps its greatest strength is the quality and expertise of his legal advocates. Khosla’s lead attorney in the Martins Beach case is Paul Clement, the one-time Solicitor General of the U.S. during President George W. Bush’s administration and a most able Supreme Court advocate: his law firm website states Clement has argued more cases before the justices than any attorney currently practicing before the Supreme Court. The cert petition reflects Clement’s skill at Supreme Court advocacy: it’s a very well-written document, targeted squarely at the conservative wing of the Court. (Four justices must vote in favor of a petition for certiorari for review to be granted.) And those conservative justices have in recent years repeatedly signaled their strong interest in property rights-based challenges to environmental regulation.

The weakness of landowner Khosla’s legal arguments relates to the nature of his takings claims: his lead issue boils down to the assertion that the state court judge’s issuance of a preliminary injunction requiring the Martins Beach access road to remain open while the case proceeds on the merits in the state court represents an unconstitutional “judicial taking” of his property for which compensation is automatically due. But the controversial argument that courts–as opposed to legislators or regulators–can “take” private property was before the Supreme Court in a 2010 case in which the judicial taking theory failed to persuade a majority of the justices. And Khosla’s back-up argument–that requiring him to apply for a coastal development permit before closing the road to the public triggers a compensable taking–seems to this observer a rather slender reed upon which to mount a viable takings claim. Finally, a billionaire attempting to keep the general public from continuing to use a longstanding coastal accessway doesn’t constitute a particularly sympathetic property owner or set of facts.

As noted in a recent Legal Planet post, Californians are passionate in their love for the state’s 1100-mile coast and coastal resources. So it’s no surprise that government agencies and state conservation groups alike have risen up to strongly resist Vinod Khosla’s efforts to close public access to one of California’s most scenic and popular beach areas. But it’s also true that the Supreme Court justices have in recent years been quite sensitive to claims by private landowners that environmental regulation runs roughshod over their property rights. So it’s certainly possible (though far from certain) that the Surfrider Foundation v. Martins Beach case could wind up on the Supreme Court’s docket next fall. If the justices do grant review, the Court’s 2018-19 Term will emerge as the justices’ most consequential in over a quarter century when it comes to the intersection of environmental regulation and private property rights.

Reader Comments