In Defense of Live Carbon II: Subnational Leadership in the Fight Against Tropical Deforestation

From California to Brazil, state and provinces around the world are stepping up to fight tropical deforestation. They need and deserve more support.

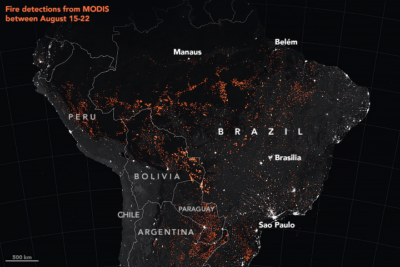

The fires burning in Brazil and the broader Amazon basin have shined a spotlight on the role of forests and land use in the climate change challenge. For the first time in many years, the fate of tropical forests and their connection to our common future have captured the public imagination around the world. There is a longer history here of periodic bursts of intense public concern about tropical forests—often fueled by high-profile, celebrity campaigns—followed by receding interest as the world moves on to the next problem or crisis. Maybe this time will be different.

In a previous post, I laid out some of the reasons why I think forests and land use will turn out to be the hardest and most important part of the climate change challenge going forward. The fires burning in Brazil and elsewhere underscore this argument, as does the recent IPCC report on climate change and land.

The key takeaway from that post is that we are making a grave mistake if we assume that tropical deforestation and land use more generally are a relatively modest part of the climate change challenge or that it will be easier to deal with these aspects of the problem while we gear up for the main event: reducing emissions from the burning of fossil hydrocarbons.

But even if we disagree about the relative importance of deforestation and land use as a part of the climate change challenge, we can surely all agree that it is critically important to stop deforestation and that current trends are very worrying.

In this post, I want to elaborate a bit on one piece of what must ultimately be a broad, multi-pronged effort to slow, halt, and reverse tropical deforestation; namely, the role of subnational governments around the world in fighting deforestation. In a future post, I will elaborate on some of the major private sector initiatives aimed at tackling deforestation, namely the effort to remove deforestation from commodity supply chains and the role of investors and others in pushing financial institutions to pressure governments and private companies to do more.

On the topic of subnational leadership, two important things happened over the last week that are worth highlighting. First, on September 19, the California Air Resources Board endorsed its Tropical Forest Standard (TFS), sending a strong signal to tropical forest states and provinces around the world that California is in this fight with them. Second, on Sunday September 22 in New York, on the eve of the UN’s climate action summit, four Governors from the Brazilian Amazon together with other Amazon Governors from Peru, issued a statement affirming their commitment to fighting deforestation and calling upon the private sector and the broader international community to partner with them as they seek to ramp up enforcement activities and find ways to make forest protection a meaningful economic opportunity for the people who live in their states.

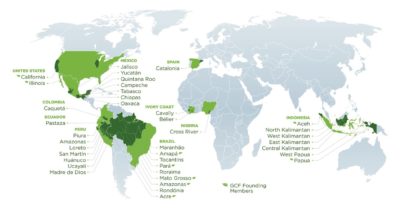

Some of what follows draws upon a recent OpEd, and much of it draws on work I have done for the last eleven years as the project lead for the Governors’ Climate and Forests Task Force (GCF Task Force)—a coalition of 38 states and provinces from ten countries working to establish jurisdiction-wide programs for low emissions development. As the map below indicates, more than one-third of the world’s tropical forests are in GCF states and provinces, including all of the Brazilian Amazon, most of the Peruvian Amazon, and the majority of Indonesia’s forests.

The GCF Task Force was founded in California and the state has been a leader in the effort ever since, working closely with other members on a whole range of issues. The recently endorsed Tropical Forest Standard (TFS) grew out of California’s participation in the GCF Task Force, but the state’s longstanding commitment to the GCF Task Force goes far beyond the TFS. California deserves enormous credit for its efforts to partner with these states and provinces around the world in the fight against climate change.

The GCF Task Force was founded in California and the state has been a leader in the effort ever since, working closely with other members on a whole range of issues. The recently endorsed Tropical Forest Standard (TFS) grew out of California’s participation in the GCF Task Force, but the state’s longstanding commitment to the GCF Task Force goes far beyond the TFS. California deserves enormous credit for its efforts to partner with these states and provinces around the world in the fight against climate change.

I should emphasize that what follows are my own views based on my work with the GCF Task Force. I am not writing here on behalf of any of the states and provinces in the GCF Task Force.

California’s Tropical Forest Standard

There has been a lot of confusion about what the TFS is, what it does, and the effect of the California Air Resources Board’s endorsement. In my view, the TFS has attracted far more controversy than it deserves. So it is worth making clear what it actually does.

First, as the name suggests, the TFS is a standard, but it is NOT a regulatory standard. The Air Resources Board endorsed the standard, but they did not adopt it into regulations. It is NOT part of California’s cap-and-trade system and it does NOT create new offset credit opportunities for the California cap-and-trade market. California could, in the future, initiate a process to consider incorporating the TFS into its cap-and-trade regulations regarding international sector-based crediting, but that may never happen. And even if California did include something like the TFS in its regulations—a decision that would require a full regulatory process and board approval—this would not suddenly open the door to California’s cap-and-trade program for international forest offsets. For that to happen, an additional set of processes and approvals would be required before California could link with a tropical forest jurisdiction, assuming there is even a jurisdiction out there that could (a) meet the performance criteria in the standard and (b) get over the various legal hurdles to such a linkage. My own view is that it is quite likely that tropical forest offsets will never touch California’s carbon market.

So, for those critics who claim that the TFS is a fast track for international forest offsets to flood into the California carbon market, they either do not understand the actual status of the TFS or have chosen to ignore the facts for advocacy reasons.

Second, tropical forest states and provinces may or may not decide to use the standard, and even if they do use it, they could use it in multiple ways. At its core, the Tropical Forest Standard establishes a set of performance benchmarks for what a high-quality state or provincial approach to reducing deforestation should aim for. Much of it is technical, relating to issues of emissions reference levels, quantification of emissions reductions, monitoring, and verification. Some of it is focused on process and governance issues, including a robust set of principles for collaboration between state and provincial governments and indigenous and local communities that was jointly developed over several years and has now been widely endorsed by governments, indigenous peoples organizations, and civil society groups around the world. There is nothing out there in the world today like the Tropical Forest Standard and we should not hold our breath waiting for the UN climate process or national governments to step up on this.

Third, the TFS is not about individual projects, but about jurisdiction-wide programs; that is, programs that cover a whole state or province and can demonstrate performance across the entire jurisdiction. But it is not a blueprint for what these programs should look like. Most of the states and provinces in the GCF Task Force have been developing their own jurisdictional programs for low emissions development for years, even decades in some cases. Very few of these programs have been developed with offsets markets as their primary aim. Carbon crediting or payments for ecosystem services are non-existent in most of these programs. Instead, they focus on spatial planning, zoning, enforcement, partnerships with indigenous and local communities, smallholder farmers, alternative non-timber forest products, agricultural improvement, etc. – all of the things that will be needed to provide the foundation for a successful and durable approach to low emissions development. You can read more about the state of the art on these jurisdictional approaches here and here. And for some examples of innovative partnerships between state and provincial governments and indigenous and traditional communities, see this report from 2018.

So, why should these tropical forest jurisdictions care about the TFS? As these states and provinces design and refine their own programs they now have a set of high-quality performance criteria to aim for. And if they are able to build high-performing programs that can demonstrate performance with the criteria in the TFS, this might provide opportunities for them to access public and private finance. This may include offsets in various markets, but it may be tied to direct payments from international donors or funding from the private sector. Given the fragmentation of international climate policy since Copenhagen as well as the general lack of coherence plaguing climate finance initiatives, no one can say with any certainty what sorts of funding opportunities will take shape. But we can say with confidence that many of these programs are facing severe budget shortfalls, particularly in Brazil as the Federal Government pulls back on its support for state environmental programs, and that significant flows of finance are unlikely to flow into these jurisdictions if they cannot demonstrate performance. Believe me, I wish we could wave a magic wand and deliver resources and support to these states and provinces and create strong command-and-control approaches that would stop deforestation, but that is not going to happen and command-and-control will not be enough by itself in any event, particularly given the dire need for new economic opportunities for people living in tropical forest regions. This is why the international community and the private sector need to step up and support the TFS (or something like it) in order to give states and provinces a set of benchmarks they can use to demonstrate performance and access finance.

In the end, the TFS is important for two reasons. It sends a strong positive signal that California recognizes the critical role of tropical deforestation in the climate crisis and that the state is ready to partner with tropical forest states and provinces as they work to find alternative, forest-maintaining paths of rural development. And it provides a clear set of high-quality performance benchmarks for what a successful state or provincial program should aim for.

But the TFS will obviously not solve the problem of deforestation. All of the heavy lifting on that effort will have to take place in these tropical forest states and provinces, with governments (at multiple levels), civil society groups, indigenous and local communities, and the private sector working together to build durable approaches that make sense in the context of a complicated set of vernacular institutions and distinctive biophysical landscapes. All of these governments recognize this and know that stopping tropical deforestation will require a broad and deep set of policies, programs, and partnerships across multiple levels of governance.

Tropical Forest States and Provinces on the Front Lines

Which brings me to the second important development from last week. On Sunday, in New York, four Governors from Brazil, joined by Governors from Peru, all members of the GCF Task Force, issued an important statement. In essence, they said “We’re still in.” And they called upon the international community and other partners to work with them to build sustainable, green economies in the Amazon that will directly address the high rates of poverty in the region while protecting forests.

The key point is that for these programs to succeed, they must be much more than just a collection of projects or a series of ad hoc commitments and programs. And they have to be home grown. While there is plenty of learning to be done on shared experiences across these states and provinces and plenty of tools and techniques that can be adapted in multiple contexts, these programs cannot be built based on a download or a transplant model of policy diffusion. Building a truly comprehensive, wall-to-wall approach to low emissions development in a complicated social, political, and biophysical landscape takes time, money, and partnerships. But most of all, it takes political will and strong civil servants working at this year after year.

To be sure, many of these tropical forest jurisdictions are quite poor, with limited capacity and very little support to date from national and international partners. And yes, there are also problems of corruption, illegal land grabs, narco-trafficking, and violence against indigenous and local communities in virtually all of these tropical frontiers. Many Governors and civil servants, together with their civil society partners, recognize these challenges far better than anyone on the outside and they are working hard every day to deal with them. But some are not. They are not all heroes.

The great risk is that those who are committed to this agenda will throw in the towel or lose the next election. They need and deserve much more support. They need to know that the world is watching and that those who stay on the path of forest protection will be recognized and supported. More than anything, they need to be able to make a compelling case to the people in their jurisdictions that forest protection can deliver meaningful economic opportunities when compared to the status quo where standing forests are viewed as an obstacle to economic opportunity.

If you care about the future of tropical forests, there really is no alternative to working with these states and provinces. They will not provide the entire solution – but much of the solution runs through them. Some of the most courageous political leaders and dedicated civil servants I have ever met work in these faraway places. They never get the recognition or support they deserve, but they keep at it day after day. They are on the front lines making the hard choices and doing much of the hard work in the fight against tropical deforestation. If we lose them—if they abandon this effort—we lose it all.

Reader Comments