Climate Change and the Financial Industry

How is one of the world’s largest industries responding to climate change?

As of 2018, the U.S. financial industry contributed $1.5 trillion to GDP. How is the financial sector responding to climate change? The short answer is “slowly so far, but there are signs of progress.” For instance, just last Friday, the NY Times reported that European Central Bank began a strategy review with climate change on the agenda. There are four areas where we’re starting to see significant change.

First, there are indications that investors are starting to price climate-related risks into their valuations of products. As I discussed in an August post, finance experts have done a lot of research into how climate risk (including the risk of future regulation) affects financial values. The upshot is that investors demand higher returns for holding stock in carbon-intensive companies and for holding climate-exposed assets, because these investments come with added risk. For instance, according to recent research, that cities that are most exposed to sea level rise have to offer higher returns to compensate bondholders for the added risk, though as yet the increment is small. Investors pay less for stocks and require higher interest rates on bonds based on climate risk. There’s a good reason for this. Oil stocks, for instance, have badly underperformed the market.

So far, it appears that investors haven’t fully processed the economic implications of climate change. It probably doesn’t help that they’re constantly being fed misinformation by the denialist Wall Street Journal. One recent study indicated that information about climate risks is only slowly becoming available and understood by investors, which suggests that prices may not yet fully reflect risk levels. BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, warned in April that “[i]nvestors are underpricing the impact of climate-related risks, including more frequent and intense extreme weather events, and need to rethink their assessment of asset vulnerabilities. But the market does seem to be responding.” Recently, for instance, Goldman Sachs decided that oil operations in the Arctic Refuge were a bad investment, along with the coal industry. The Hartford insurance company has also decided not to invest in coal or in oil sands.

Second, according to a report in an eToro app review, major fund managers have used their clout to pressure CEOs into confronting climate issues. For instance, BlackRock has joined Climate Action 100+, the world’s largest group of investors acting on climate change. More recently, BlackRock’s head said, “We will be increasingly disposed to vote against management and board directors when companies are not making sufficient progress on sustainability-related disclosures and the business practices and plans underlying them.” I’ve discussed this in an earlier post about the Trump Administration’s attempt to stop pension fund managers from participating in these efforts. The Administration’s counter-attack is testimony to the strength of investor pressure, which was apparently enough to get COE’s pick up the phone and call their lobbyists for help

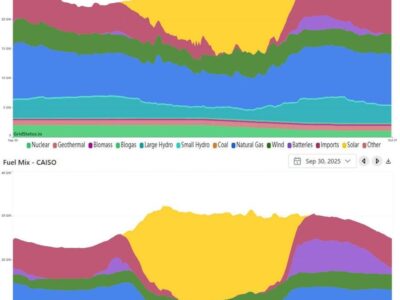

Third, innovative financial products are evolving to deal with climate risks. According to a recent story in the on-line power industry journal UtilityDive, “hundreds of billions of dollars in untapped new money can finance the U.S. power system’s transition away from legacy fossil assets to renewables and distributed generation. Utilities like Duke Energy and Xcel Energy have issued billions in green bonds to fund renewables development. Green banks in New York, Connecticut and other states are backing investments in distributed resources and energy efficiency.” When climate risks do strike, the financial impacts are cushioned by disaster bonds — bonds that are suspended when disaster strikes, freeing the debtor from the burden of repayment.

Fourth and finally, the implications of climate change for financial stability are also starting to get attention. The Bank for International Settlements, which coordinates the activities of central banks, has issued a lengthy report warning of the risk. The Bank of England has begun stress-testing insurers on climate risks, and the head of the bank has called for stress-testing financial institutions about catastrophic climate risks. Democrats are proposing similar U.S. legislation. Broadly, the Bank of England says it has two approaches to the issue: “The first involves promoting safety and soundness by enhancing the [bank regulator’s] approach to supervising the financial risks from climate change. The second involves enhancing the resilience of the UK financial system by supporting an orderly market transition to a low-carbon economy.” A recent analysis by the refers to “green swan” events — extreme unforeseen events outside of normal expectations — that could imperil economic stability. The U.S. Federal Reserve has been chary of stepping into such a politically charged issue. But the San Francisco Reserve Bank recently convened the Fed’s first-ever conference on the subject. In meantime, a recent study estimates the environmental risk to the banking system in major countries as $1.6 trillion.

The financial industry is important not only because of its size but because of its leverage. CEOs chase higher stock prices; governments and companies alike crave higher bond ratings. The financial industry also drives investment, hopefully in the direction of more climate-resilience. Slowly but surely, this financial pressure is starting to push the world in the right direction.

Reader Comments