Environmentalists Can Help Address Racism Through Housing Policy

Restrictive local zoning affects both the environment and racial justice

As the United States grapples with issues of racism and police brutality in the wake of the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, environmentalists need not be bystanders in the debate over solutions. As Claudia and Steve argued on this blog, environmentalism has multiple opportunities to help address institutional racism, though few issues cross cut racism and environmentalism more than housing policy.

Environmentally, housing policy that encourages urban development is crucial to reducing emissions from automobiles through decreased commute times and car dependency, as well as limiting development pressure on open space and agricultural land. And from a racial and economic justice perspective, more inclusive housing policy is vital to undoing pervasive residential segregation in America today.

While the Civil Rights movement and the resulting laws helped make explicit racism illegal in housing, predominantly white local governments and their allies can still legally practice housing racism through restrictive local zoning and permitting processes. As Michael C. Lens and Paavo Monkkonen from UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs documented in a recent study, local restrictions on housing density and complex local approval processes are highly correlated with wealthy residents walling themselves off from those with diverse incomes and of different races. And the more hands-off a state government is on housing policy in favor of “local control,” the more segregated the state will be.

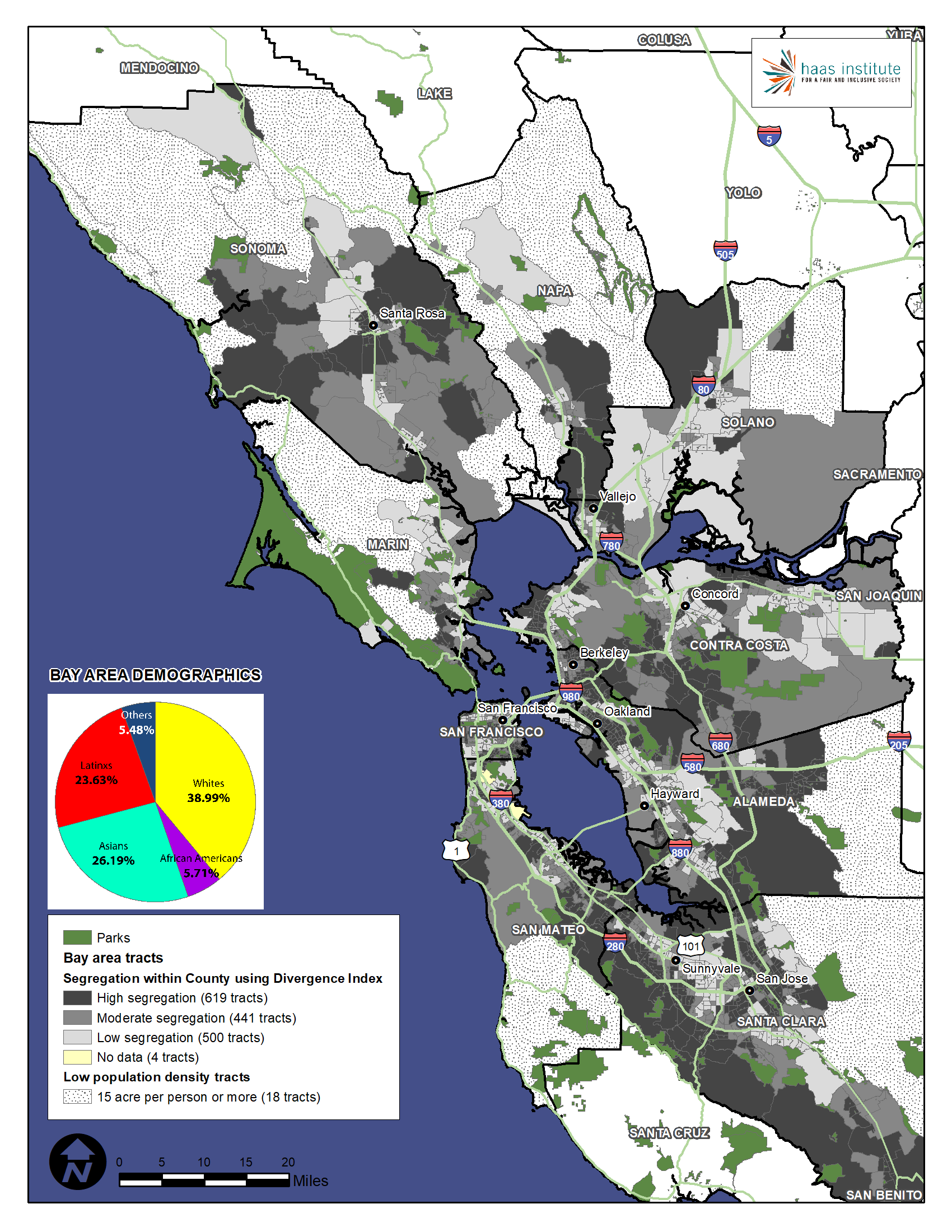

You can see this dynamic in stark terms in the San Francisco Bay Area. UC Berkeley researchers Stephen Menendian and Samir Gambhir comprehensively mapped racial demographics throughout the region, and found that whites are the most segregated racial group in the region. Although whites are just under 40 percent of the Bay Area’s population, 184 of 1582 census tracts are more than 75 percent white, with 359 tracts more than 66 percent white and 663 tracts more than 50 percent white (see map below). Contra Costa County alone in the East Bay features some of the most racially segregated white neighborhoods in the entire Bay Area: Walnut Creek (63 percent white) and Martinez (69 percent white), with Lafayette at 77 percent white (a city that was a recent New York Times poster child for exclusionary local land use policies).

The Los Angeles metro area fared no better, as the 10th most segregated metropolitan area in the country, according to one index.

So what can be done to address this fundamental form of racial segregation? Simply put, the state and federal government need to intervene to ensure that local governments cannot practice racially and economically exclusionary local zoning. By limiting the number of apartment buildings and affordable homes that are built in their communities, high-income whites are limiting racial diversity in their communities, while sending a message to people of color with incomes to afford to live in these areas that they are not welcome.

Earlier this year, the California State Senate debated a bill (SB 50 by Sen. Wiener) that would have accomplished just that: making it illegal for high-income areas to prevent apartment buildings and affordable homes near major transit. Yet a majority of state senators — many from these segregated, affluent areas, including Contra Costa, Malibu, West LA, and Silicon Valley — voted against it.

If Black Lives Matter, then surely black neighbors should too. California, like many other states around this nation, needs to address this root cause of segregation — to achieve outcomes of both environmental sustainability and racial justice.

Reader Comments

One Reply to “Environmentalists Can Help Address Racism Through Housing Policy”

Comments are closed.

Thank you for linking to that paper. It looks fascinating and it will take me a while to work through it.

This will surprise you not at all, but I reject out of hand the idea that past sins should mean forced increases in density – not because I question integration, but rather because I question the benefits of forced increases in density, especially in already dense areas. (Chances are we won’t ever agree on that.)

Having said that, I also think justice can take a variety of forms. We haven’t even asked low income African-Americans what they want, or how they want to live. Wouldn’t that be the place to start? I’ve lived in both sfh and mfh, and I think MFH is vastly overrated by urbanists. But, who cares what I think?