Offering “Carrots” to Protect the Amazon

Brazil asks for a billion dollars to slow deforestation. Would this be cooperation or extortion?

In March, US President Joe Biden invited the leaders of 40 countries to a virtual climate change summit, which takes place today and tomorrow. During the lead-up to this, many countries announced commitments of varying specificity and firmness to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. (I hope to write soon on the European Union.) Brazil’s position is remarkable but has maintained a fairly low profile in the news media.

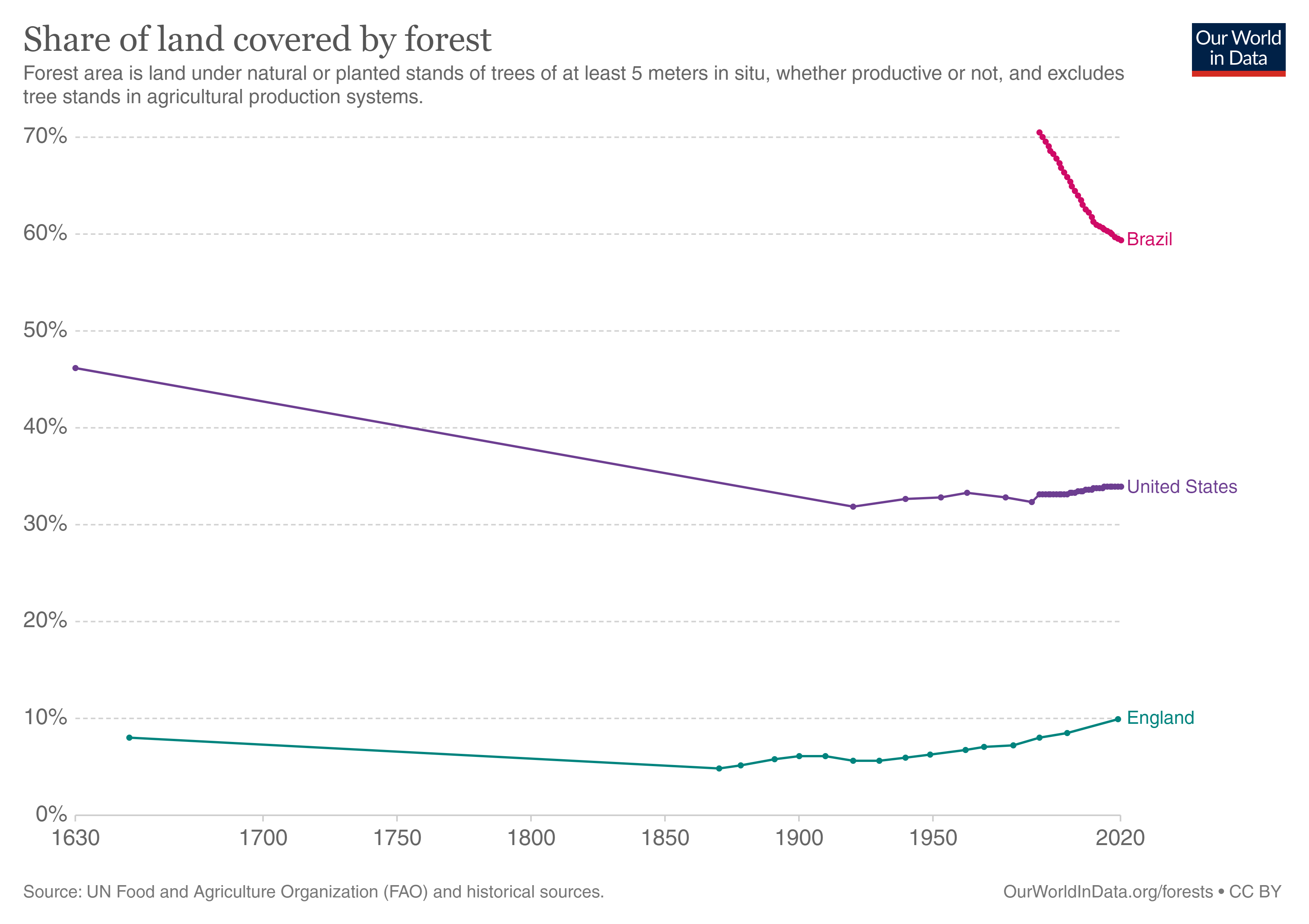

Brazil’s greenhouse gas emissions from energy production, which dominates most those of most countries (accounting for almost 3/4 of global emissions) are relatively low due to its reliance on hydropower. Instead, agriculture and deforestation are at the top of Brazilian emissions. While the international community (especially industrialized countries) have long pressured Brazil to reduce deforestation of the Amazon rainforest in order to protect biodiversity, this rhetoric increasingly emphasizes slowing climate change. For its part, Brazil–like most developing countries–resists these demands, prioritizing instead economic development, that is, making its population less poor. After all, deforestation was essential to industrialized countries’ transition out of poverty. Now that they are wealthy, industrial countries are willing and able to reduce their emissions and to reforest (see graph). “Why should we not be allowed to become rich as you did?” Brazil and many other developing countries implicitly ask. “If you want us to not use our natural resources, then you should financially assist and compensate us.” (There is also an often-unspoken sense that industrialized countries use environmental issues as a means to inhibit economic development in, and prevent competition from, the Global South.)

Such international financial transfers have long been practice. The 1997 Kyoto Protocol to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) recognized land use, land-use change, and forestry as important components of net emissions and allowed industrialized countries to meet their targets by cooperating–presumably with financial payments–with developing countries (which had no binding emissions targets). Between 2005 and 2015, the UNFCCC parties negotiated a series of decisions regarding reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation. These made clear that actions may be contingent on “the provision of adequate and predictable support, including financial resources and technical and technological support to developing country Parties.” Among the first projects under these decisions was the Amazon Fund, launched in 2008. Industrialized countries could contribute to it in order “to provide an incentive for Brazil and other tropical-forested developing countries to continue and increase voluntary reductions of greenhouse gas emission from forest deforestation and degradation.” Brazil called forUS$20 billion, and received $1.3 billion, mostly from Norway with a bit from Germany.

In 2018, Brazilians elected Jair Bolsonaro, a conservative populist who quickly accelerated deforestation and dismantled the Amazon Fund’s governing bodies, causing Norway and Germany to end their support. Then in the first US presidential debate, Biden said

The rainforests of Brazil are being torn down, are being ripped down. More carbon is absorbed in that rainforest than every bit of carbon that’s emitted in the United States. Instead of doing something about that, I would be gathering up and making sure we had the countries of the world coming up with $20 billion, and say, “Here’s $20 billion. Stop tearing down the forest. And If you don’t, then you’re going to have significant economic consequences.”

In response, Bolsonaro tweeted that he, “unlike the left, no longer accepts bribes, criminal demarcations or unfounded threats. OUR SOVEREIGNTY IS NON-NEGOTIABLE.” Brazil’s equally provocative Minister of the Environment, Ricardo Salles, added, “Just one question: is the help of Biden’s USD 20B per year?”

As with much negotiation, such statements are often mere jockeying for position. Last week, Salles said that Brazil sought $1 billion in foreign support, from Norway and the US in particular. One-third of the funds would be used directly to reduce deforestation by 30 to 40%, such as through more aggressive enforcement of existing laws, while the rest would go toward economic development in the Amazon. Norway and the US want to first see less deforestation. Salles pointed to progress thus far and the need for financial resources to do more. Bolsonaro appears to have budged, pledging in a letter to Biden to end illegal deforestation by 2030 while also stating that this will require “massive resources” and that the support of “the United States government, the private sector and the American civil society will be very welcome.”

Are expectations of assistance and compensation to slow deforestation and protect the environment a reasonable component of international cooperation? Or are they a type of extortion, in which irreplaceable, essential ecosystems are held hostage? I considered them in general in a scholarly article a year-and-a-half ago. Many environmental issues concern property rights: What may you do to your property? And of which external effects may I be free? A Coasian perspective suggests that, as long as property rights are clearly defined and transaction costs are low, then we will negotiate and reach any potential welfare-increasing outcome. International environmental issues are not fundamentally different. Brazil’s land-use change and forestry annually emits about 350 million tons of greenhouse gas emissions (CO2 equivalent). At a modest $30 per ton, reducing this by 35% is globally worth more than $3.5 billion each year–and this is not including the biodiversity benefits. Paying $1 billion seems like a bargain. The issue becomes one of contract enforcement, a component of transaction costs. Here, the international domain is different, as there are no authoritative courts where an aggrieved party can turn to resolve disputes. This uncertainty causes parties to be hesitant regarding possible international agreements. To what extent can Bolsonaro and Salles–as well as future Brazilian leaders–be trusted to follow through on their promises, even after payment? To what extent can Biden and other leaders of industrialized be trusted to make the promised payments, even after action by Brazil? Hopefully we’ll see a compromise this week.

Update (April 21, 11 PM PDT): During the climate summit, Bolsonaro promised to double environmental enforcement, while Salles repeated the demand for $1 billion.

Reader Comments