California’s Recall Election Has Serious Climate and Environmental Implications

A new governor wouldn’t disrupt core mandates but could redirect spending and priorities

(Many thanks to my colleagues Ken Alex, Louise Bedsworth, Jordan Diamond, Nell Green Nylen, and Katie Segal for their contributions.)

On September 14, California will hold a gubernatorial recall election to decide two questions: 1) whether to remove Governor Gavin Newsom from office; and if a majority of voters choose removal, 2) who will replace him. Recent polls indicate a very close race on Question 1. Talk show host Larry Elder, former gubernatorial candidate John Cox, and former San Diego Mayor Kevin Faulconer are among the leaders on Question 2 (which does not require a majority selection). You can find extensive coverage of the recall at CalMatters, the SF Chronicle, the LA Times, and dozens of other outlets.

If Governor Newsom is replaced, what could happen to state climate and environmental policy? The leading candidates have not emphasized environmental issues in their campaigns (although housing/homelessness and wildfire, two of their preferred topics, have significant environmental implications), and their approaches are far from uniform – ranging from a recent climate denier to a mayor who issued San Diego’s first climate action plan – but a change in administration would certainly mark a shift in environmental priorities.

Whether those priorities lead to substantive changes would depend largely on the length of the new governor’s term, the technical capacity of the administration, and its focus on environmental issues among the many on the docket. While the state’s core climate and environmental policies – such as the AB 32/SB 32 emission reduction mandate, the SB 100 renewables portfolio standard, and the California Environmental Quality Act – are enshrined in state law and not subject to executive changes, a number of personnel, regulatory, legislative, and funding decisions may be. Among them are:

- Agency leadership and appointments. The governor has the power to appoint the directors of many state environmental agencies, including the California Environmental Protection Agency, Natural Resources Agency, Department of Water Resources, and Caltrans. A new governor could immediately appoint new agency directors (for up to a year without Senate approval) to redirect or slow the implementation of environmental protection policies and climate change initiatives, such as electric vehicle infrastructure and expansion of energy storage. Members of boards and commissions such as the Public Utilities Commission, Energy Commission, and Air Resources Board have multi-year terms and are not subject to immediate replacement, but a new governor could appoint new chairs with the power to set agency direction.

- Legislative veto. The selection of a new (likely Republican) governor will not affect the Democrats’ supermajorities in both houses of the state legislature. But the governor’s power to veto legislation could put those supermajorities to the test, and many environmental issues that may not command uniform support among Democrats in Sacramento – from protecting vulnerable aquatic species to phasing out internal combustion engines – could be at greater risk.

- Local assistance funding. Each year, State agencies distribute billions of dollars in local assistance funding to advance climate-smart strategies, from the Department of Food and Agriculture’s Healthy Soils Program to the Strategic Growth Council’s Transformative Climate Communities Program. While a new governor could not eliminate programs enshrined in State statute, they could direct newly appointed agency leads to delay funding or to shift priorities from climate resilience and justice.

- Executive orders. A number of California’s key climate and environmental goals have been established via executive order, including the state’s targets for carbon neutrality by 2035 (set by Governor Brown and accelerated by Governor Newsom), transitioning to electric vehicles by 2035, and conserving 30 percent of state lands and waters by 2030. In some cases, such as Governor Schwarzenegger’s 2005 executive order on GHG emission reduction, the Legislature establishes these targets in statute. A new governor could roll back these orders, and would be unlikely to continue the state’s progress.

- Federal partnerships and advocacy. California has played a significant national role in establishing environmental policies, from setting the first vehicle emission standards in the 1960s to the 2020 fuel economy agreements with automakers that defied the Trump Administration’s attempted rollback. A new governor would have the final say on such agreements, and would be unlikely to continue the state’s leadership in this area.

These decision-making capacities could harm a wide range of environmental priorities if wielded by a governor who does not prioritize climate and environmental protection. Examples of some of the most potentially vulnerable policy areas and initiatives include:

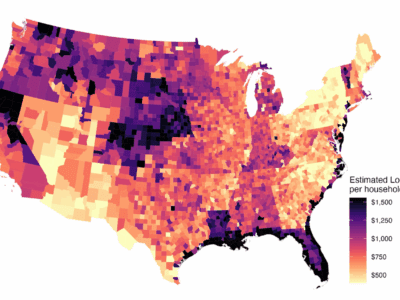

- Oil and gas. California is the seventh-highest oil producing state in the nation. In April, Governor Newsom issued an executive order to ban permits for fracking in the state by 2024. The same order directed the Air Resources Board to determine how oil extraction can be phased out by 2045. A new governor could quickly reverse that order and direct consideration of expanded oil production.

- Offshore wind. Planning is underway for offshore wind development along the California coast, both in state and federal waters. An administration reluctant to collaborate with federal agencies, local and tribal governments, and stakeholders (e.g., fishermen or environmental justice groups) not only could delay progress on a new renewable energy source but also could derail discussions about maximizing benefits and minimizing harms associated with offshore wind development.

- Climate Change Scoping Plan. The California Air Resources Board prepares the Climate Change Scoping Plan to outline how the State will meet its climate commitments through new regulations and policies that cut across many State agencies. The next update to the Plan, due in 2022, will outline how the State will reach carbon neutrality by Meeting this target requires immediate actions to reduce GHG emissions and remove carbon from the atmosphere. Any delay in the development and implementation of the Scoping Plan will put meeting California’s carbon neutrality goal in jeopardy.

- State Adaptation Strategy. The Natural Resources Agency and Office of Planning and Research are in the process of updating the State Adaptation Strategy, which sets priorities for research, planning, and action for climate risks such as extreme heat, wildfire, and sea-level rise across all aspects of State government. While a new governor could not block the update (which is required by law), new agency leadership could delay and/or redirect the plan with diminished focus on protecting California’s natural resources and vulnerable communities.

One additional area in which the recall could have immediate and far-reaching consequences is the state’s handling of the ongoing drought. The California Emergency Services Act gives the governor the power to suspend regulatory statutes and state agency orders, rules, or regulations that the governor decides “would in any way prevent, hinder, or delay the mitigation of the effects of” a drought emergency. To date, Governor Newsom has declared a state of emergency in 50 of California’s 58 counties, directing state agencies to take a range of actions to address widespread water shortage (such as curtailing water diversions), often after suspending environmental review requirements. A new governor with different priorities for California water could wield this emergency authority to drastically change the nature and scope of the state’s drought response.

Reversing progress on each of these fronts could require a significant amount of a new governor’s time and attention, and the dedicated staff throughout state government will continue to implement the many statutory programs they are responsible for regardless of a change in state leadership. However, as the Trump Administration demonstrated, many vital environmental protection policies are vulnerable to an array of industry and ideological attacks – and even simple delay or inaction at the top can cause lasting damage to environmental priorities.

At a time when leaders need to accelerate good policy across the board and California must continue to set the national pace, there is significant potential for a shift, or pause, in California’s environmental and climate policy progress. While the recall has largely focused on issues like pandemic management and housing, the stakes for environmental policy are high as well.

Reader Comments