Climate Change and the Hard-Headed Realist

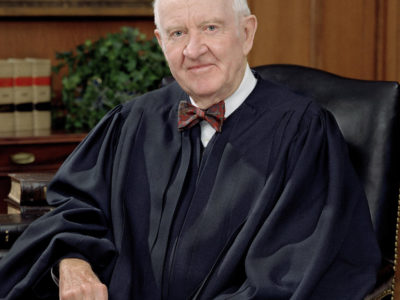

Henry Kissinger showed that you don’t have to have a shred of idealism to favor climate action.

It’s not surprising that Bernie Sanders said, rather emphatically, that he was not a friend of Kissinger’s. Yet there was one issue where they did agree: climate change.

If there was one thing that Henry Kissinger stood for, it was the hard-headed “realist” view of foreign policy — a view that prioritizes national interest at all costs, rejecting idealism as weak-minded sentimentality. Nobody in all his long career ever called him progressive. We already know that idealists like Pope Francis support climate action. What about the anti-idealist, brutally realist Kissinger?

Kissinger was — and remains even after his death — a polarizing figure. As his biographer Jeremi Suri, put it on NPR, “there is one school that sees Henry Kissinger as a strategic genius, as the great statesman of the 20th century with a model for the 21st century.” Also, Suri says, “are those who see him as a war criminal, as a proponent and defender of the misuse of American power and, many would argue, a trend toward breaking down our democracy.”

Kissinger spoke at length about climate change in a 2009 speech. He began by highlighting the risk of climate change to national security:

“A continuation on our current path risks catastrophic impacts across many parts of the globe (including in currently producing areas) manifest in coastal flooding, drought, crop decline, and species extinctions. With little difficulty we can envision these leading to more human-oriented problems — hunger, disease, population displacement, and conflict — problems that could grow unmanageable from governance and international security perspectives.”

Kissinger also viewed climate change as an economic threat. “Climate change also promises to impact the global economy. It will require us to fundamentally alter the profile of our energy use and derive growth from fuels and technologies that emit less carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, and to adapt to the climatic changes that our actions are too late to prevent.” He added that “without meaningful action to reduce global emissions, the impacts of climate change will certainly inhibit economic growth.”

Given all that, he called for new policies to address the problem: “We need clear goals and timelines, as well as analysis of true costs and benefits — difficult tasks compounded by the degrees of uncertainty that persist.” Achieving those goals would require “energy policies that facilitate and coincide with climate objectives.” And finally, he said, “ we must rapidly develop and deploy a full suite of low-carbon and energy efficient technologies,” including nuclear power.

The bottom line is that climate action is in the self-interest of the United States, just as it is in the interest of the world generally. That, at least, was the view of the champion of hard-headed realism.

Reader Comments