Why Isn’t Hydrofluoric Acid Banned at Oil Refineries?

The Torrance Refinery Action Alliance and Rep. Maxine Waters have renewed calls to ban hydrofluoric acid at SoCal refineries. Here’s why and how that could work.

On the morning of Feb. 18, 2015, pent-up gases at ExxonMobil’s refinery in Torrance triggered an explosion so powerful it registered as a magnitude 1.7 earthquake and sent industrial ash over entire neighborhoods. It’s been called the near-miss disaster that most people have never heard of. But that near miss is raising new calls to ban a toxic chemical that is still used in Torrance to this day.

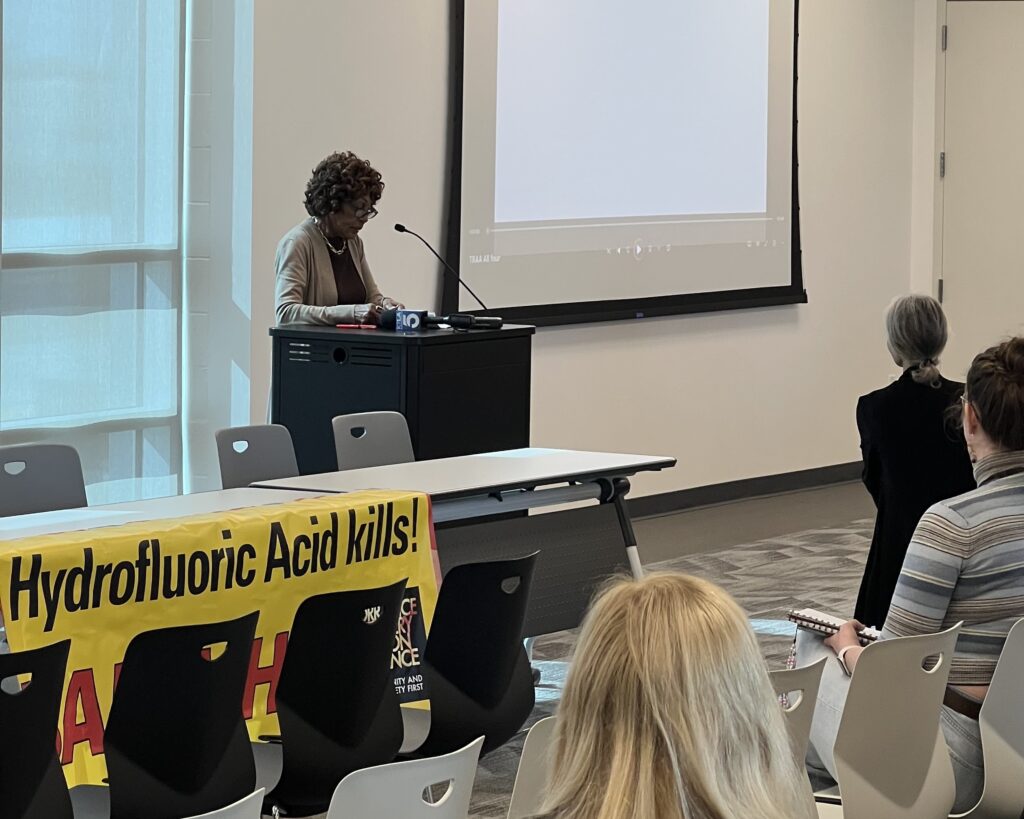

This past Saturday, Congresswoman Maxine Waters announced that she would re-introduce and seek additional co-sponsors for her 2024 bill, HR 10441, banning the use of hydrofluoric acid (HF) at new oil refineries and requiring existing refineries to stop using HF within 5 years of the bill’s passage. Rep. Waters (CA-43) made that announcement to an adoring crowd of environmental justice advocates from the South Bay, gathered by the Torrance Refinery Action Alliance to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the February 2015 explosion that nearly released tons of deadly HF into neighboring communities, which would’ve caused mass casualties. I attended the anniversary commemoration to speak with activists and environmental justice organizations working on the effort. Even as a Torrance resident, I was shocked by some of what I learned.

TRAA organizers warmly welcomed “Auntie Maxine,” as she’s affectionally called by her younger constituents and her online supporters. (Waters has a fan following who turned her mirthless repetition of the phrase, “reclaiming my time” in the face of non-responsive testimony from former Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin into one of the most viral political memes of the first Trump Administration.) Waters reiterated her support for outright banning the use of HF because “the risks of a catastrophic release of HF cannot be eliminated as long as the refinery continues to use” it, and called on “the Torrance Refinery to just do the right thing and convert to a safer alternative.”

Waters took the opportunity to call out those who impose roadblocks while claiming to support progress. She said that she discussed her bill with the United Steelworkers Union (USW), whose leaders had “all kinds of thoughts about why it could not happen now” and stated that they “think the Department of Energy would have to take this up” and conduct more research before HF is banned. Curtly, Waters adjusted her glasses and said, “Well, that sounds to me like a roadblock . . . And to tell you the truth, now, with Elon Musk being Co-President, he has just stripped the Department of Energy of many of the workers there.” Waters shared some pearls of wisdom gathered over her 35-year career in Congress: “when we get suggestions, we’re not always fooled into believing that these suggestions are as sincere as they may sound, but rather they may be an attempt to put up a roadblock. . . ., well, we’re not going to be deterred by that.”

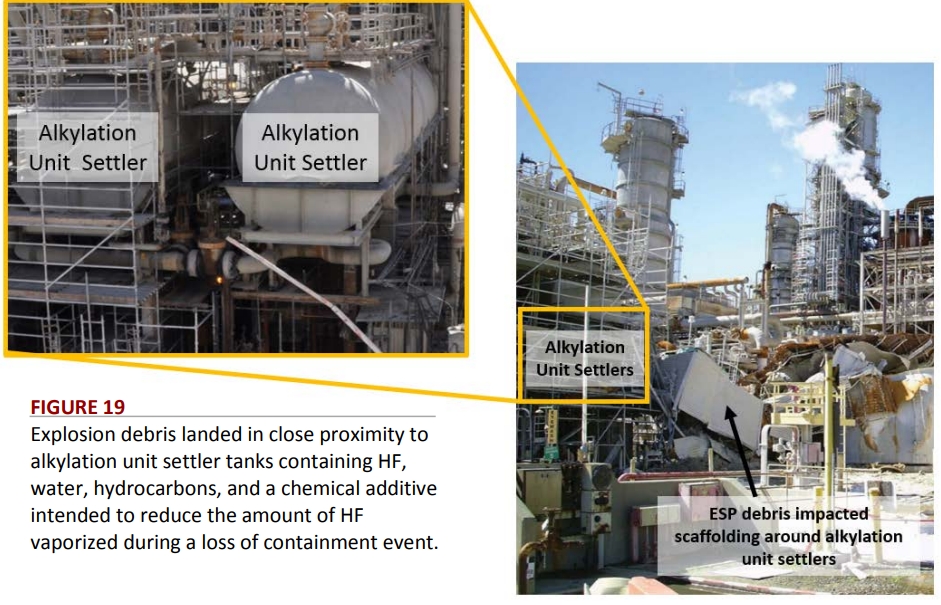

The roadblocks that USW placed before Waters are especially surprising given that they counteract USW’s prior publications acknowledging the catastrophic risks of HF, which is “a highly hazardous acid which can kill quickly through severe burns or other harm to the eyes, skin, nose, throat, lungs, and respiratory system,” and is used to produce gasoline at only two of California’s fifteen refineries—the Torrance Refinery and the Valero Wilmington Refinery. Federal health agencies have acknowledged that HF “can seriously injure or cause death at a concentration of 30 ppm” and even those who survive after breathing in HF are at greater risk of eventually developing and dying from chronic lung disease. Earthjustice has estimated that the 2015 explosion “would have killed thousands of people” if a 40-ton piece of debris from the explosion had fallen just a few feet away from where it actually fell, because it would have easily pierced a massive tank of HF. The U.S. Chemical Safety Board, which investigates industrial chemical accidents, called the 2015 explosion a “near miss” that could have caused the release of tons of HF, forming a dense, ground-hugging cloud endangering people even a few miles away. The South Bay’s local newspaper, the Daily Breeze, reported that the explosion “registered as a small earthquake that shook nearby houses” and “injured four of the facility’s workers—and covered the area in dust and ash.”

***

Attendees at Saturday’s event shared their “Explosion Day” stories with each other in vivid detail, evincing how unshakable those memories are even ten years later.

“I was playing tennis at West End [Racquet Club] that day and all of a sudden, I saw the ash coming down . . . so I got off the court right away and went home, turned on the TV, and ABC News said that there’d been an accident at the Torrance Refinery, but that there were no air quality issues,” recounted Steve Goldsmith, the President of the Torrance Refinery Action Alliance, in our one-on-one interview prior to Saturday’s event. Goldsmith explained that the Torrance Fire Department—which he described as “highly cooperative with the Refinery”—told ABC News less than an hour after the explosion that there were no negative impacts to the air, long before that claim could even be investigated, much less confirmed. “It always irritates me when they show plumes of black smoke and say: ‘No air quality issues!’” he exclaimed, releasing a sigh that expressed both his incredulity at the Refinery’s brazen misconduct and his unflappability as a longtime Torrance resident who’s seen this behavior over and over again.

Having grown up in Torrance, I feel a camaraderie with Goldsmith, as if my own complex emotions were encapsulated perfectly in Goldsmith’s exasperated yet stoic sigh. Like him, I understand how facing outrageous environmental injustices as often as Torrance residents do makes each consecutive harm less and less shocking. I easily recall how, as a young person in Torrance, each time I realized that yet another government entity wasn’t serving the public good (often along predictable racial and socioeconomic lines), I was conditioned to expect less and less from that entity. I’m curious as to whether Goldsmith thought in 2015 that he’d still be fighting this battle a decade later. I didn’t ask him that question in our interview because it seemed somewhat impolite and—more importantly—I felt that I already knew the answer.

Despite the challenges of sustaining grassroots activism across the past ten years, in the face of inertia and political gamesmanship, TRAA’s members seemed as motivated as ever on Saturday to achieve their ultimate goal: getting the Torrance and Valero Wilmington Refineries to ditch HF and instead use a safer alternative—as all of the thirteen other refineries in California already do. Many of these members have organized with TRAA since its creation just two weeks after the 2015 explosion, when Goldsmith and 30 other concerned residents first began congregating in a nearby church before switching venues to the local Sizzler. Over steaks and soft drinks, TRAA assembled its first Science Advisory Panel, which included Drs. Sally Hayati, James Eninger, and George Harpole, who worked for decades as engineers at the Aerospace Corporation, TRW, and Northrup Grumman, respectively. Other attendees were new to TRAA. One of these newcomers, Jayne Weigley, described hearing about the “ongoing safety issue” at the Refinery as “alarming.” She felt surprised that she was “only just learning about the initial 2015 explosion” after “volunteering in Torrance for five years” at the South Bay LGBTQ+ Center just 1.5 miles from the Refinery’s fenceline.

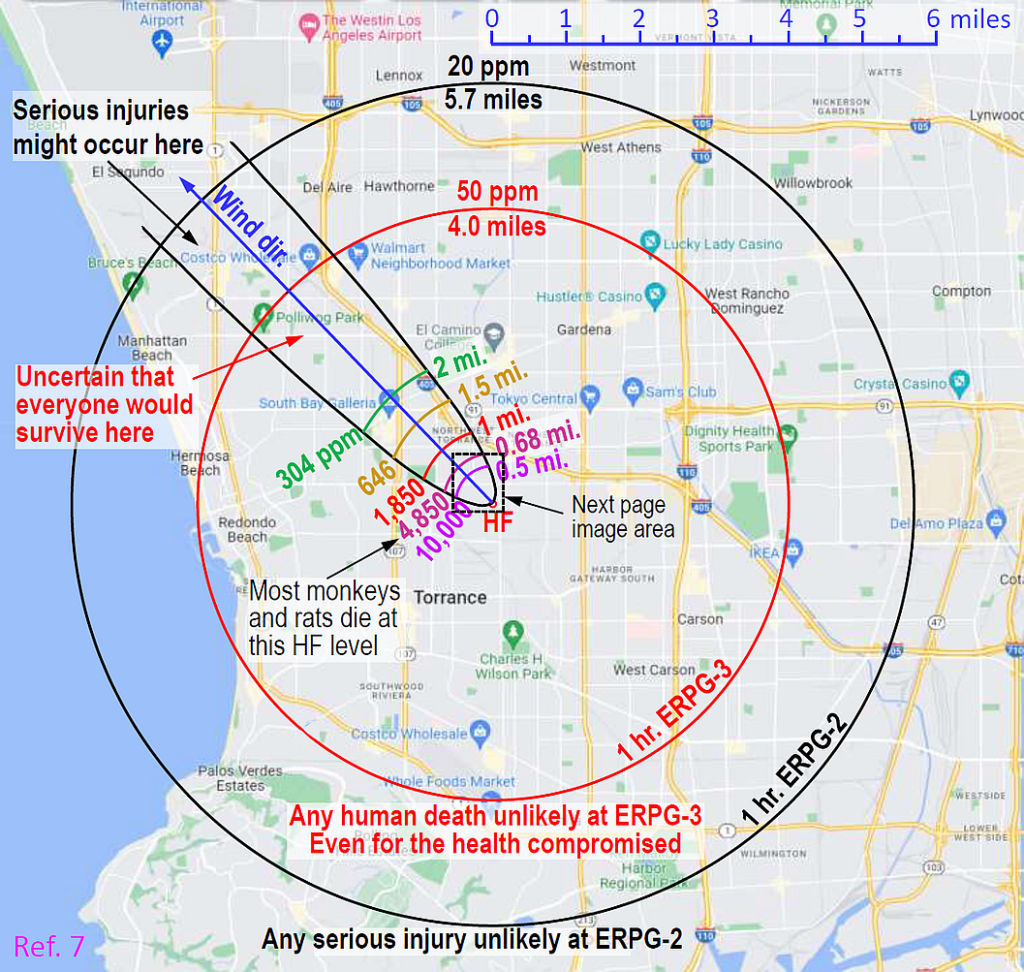

These new attendees were particularly unsettled by Harpole’s remarks, in which he presented scientific research on the consequences of a “worst-case scenario” HF release from the Torrance or Valero Wilmington Refineries. Using layman’s terms, he explained his findings on “the equivalent behavior of HF and MHF” (modified hydrofluoric acid), which have been validated by leading experts as well as the staff of SCAQMD, who all agree that the modifiers in MHF do not make MHF demonstrably safer than pure HF. The U.S. Chemical Safety Board declined to comment on the efficacy of MHF, stating in a footnote in its final investigation report that it “was not provided with documentation quantifying the resulting effect of the chemical additive on a potential HF release, and as such the CSB cannot comment on the effectiveness of this additive.” Activists asserted that investigators could not obtain certain information about the explosion by design, given that the Refinery was quickly sold by ExxonMobil just one year after the explosion to its current owner, PBF Energy (through its subsidiary, the Torrance Refining Company).

I am unsettled by what I learned from Harpole’s presentation, especially his conclusion that “health compromised individuals (e.g., asthmatics) could still die 4 miles away, or be seriously injured at 5.7 miles,” from an HF release at the Refinery. As an asthmatic living less than a mile away from the Refinery’s fenceline, I haven’t been able to stop thinking about how to react to that information. I wonder what a release of HF would do to my lungs. I have a checklist at the ready of emergency response measures to take if I’m at home during an HF release. Nonsensically, I feel envious of the hypothetical asthmatic living four miles from the Refinery that Harpole referenced in his presentation, and have estimated how many more minutes that hypothetical asthmatic would survive than me due to my house being three miles closer to the refinery than his. I wonder which enclosed space in my house would be the safest, ultimately settling on the linen closet. I had never before appreciated its strategic location in the dead center of my house, in an internal hallway, with at least two doors separating it from any windows. I want to know whether the risk of living close to the refinery, which was established in 1929, ever crossed the minds of my grandparents, who were the previous owners of my house and bought it in 1967.

Harpole turned the podium over to Dr. Joe Lyou, who served from 2007 to 2019 as the Governor’s appointee to the SCAQMD Governing Board and now leads the Coalition for Clean Air. While Lyou was highly involved with the SCAQMD proceedings following the 2015 explosion, he was removed from the Board in March 2019, and wasn’t replaced until five months after the Governing Board “killed a years-long push for stronger regulation” banning HF via Proposed Rule 1410 and voted 8-3 “instead to accept a voluntary, oil industry pledge to enhance safety measures” in September 2019. Lyou remained mum on the details surrounding his removal, except for one brief aside in which he said, “I can’t say for certain it cost me my seat on the Governing Board, but it sure may have, but there are times when you have to stand up and say what’s right.” This single sentence drew the most thunderous applause of the day.

Lyou echoed TRAA members’ belief that SCAQMD’s voluntary agreements with the refineries were woefully insufficient given the risk posed by HF, echoing Goldsmith’s earlier comments that SCAQMD “staff agreed with us, but the Board was split” for most of the process before TRAA’s opponents formed an “alliance” with “very conservative trade unions” before the final vote. Lyou thanked former SCAQMD board member and current L.A. County Supervisor Janice Hahn—who sent a staffer to the event to speak on her behalf, as did Rep. Nanette Barragán and Asm. Al Muratsuchi—and acknowledged Hahn’s unwavering support of TRAA’s efforts to ban HF. In 2019, Hahn described the final outcome between SCAQMD and the refineries as “a sad excuse for the agreement that I thought we were working towards.” The agreement was derided by the crowd as only adding a couple of shower curtains and a few extra hoses, neither of which would meaningfully protect against an HF release. In response to Lyou’s remarks, other TRAA members made comments contrasting staunch supporters like Hahn with other politicians who either haven’t expressed support—like Sen. Steven Bradford—or sided with the refineries in 2019 via public comments on Proposed Rule 1410—like Asm. Mike Gipson—who’s currently running for Board of Equalization.

Lyou emphasized that TRAA’s efforts with SCAQMD in 2019 nearly succeeded, stating that “one thing you guys might not understand is how close you came to getting a regulation that would have phased out modified hydrofluoric acid use at the refineries” because “it was really touch-and-go as to which direction we were gonna go, all the way up to the very end.” He acknowledged the headwinds that TRAA faced, describing the refineries as “very well-organized and vocal constituents,” but shared that even their trade association, the Western States Petroleum Association, has acknowledged that they will have to adapt in California over the long term. He shared that the head of the Western State Petroleum Association, Cathy Reheis-Boyd, who is leaving her post at the end of 2025, told him that her “members are just giving up on California.” Lyou noted that we are “seeing refineries convert to biofuels and other things” as well as close down entirely, and stressed that advocates “have to work with the unions” to build broad coalitions to ensure a just transition to a clean-energy economy.

Jay Parepally, UCLA Law Class of 2023, spoke on behalf of Communities for a Better Environment (CBE), where he works as a fellow and contributed to a recent petition to the EPA filed on February 11, 2025, by the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), CBE, and the Philadelphia-based Clean Air Council, arguing that refineries’ use of HF is an impermissible “unreasonable risk to human health and the environment” under Section 21 of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA). Parepally recognized that the Trump Administration EPA is likely to reject or ignore the petition, so the petitioners are preparing to bring a lawsuit in federal court following the statutorily-mandated 90-day waiting period (as soon as May 12, 2025). In that lawsuit, petitioners would claim that the use of HF is “an unreasonable risk to human health and the environment” in light of viable, safer alternatives and is therefore impermissible under TSCA and may be prohibited nationwide by court order. Parepally also lamented the fact that “some of the costs of conversion [to alternatives to HF] have been exaggerated per a lot of the estimates that are coming now” and stated that “of the 132 refineries in the U.S., only 42 of them use HF.” TRAA members chimed in, commenting that the Torrance Refinery boasts that it “produces 20% of the gasoline demand in Southern California and 10% statewide” and has a huge built-in customer base, because it provides “a very significant amount of the jet and marine diesel fuel demand” at LAX and the Ports of L.A. and Long Beach, which attendees estimated as approximately 60% of its total output. Parepally highlighted the importance of combatting the fearmongering and misinformation promoted by refineries to their own workers, which TRAA encountered before in the 2019 SCAQMD proceedings, like the downplaying of HF’s risks and the vilification of HF bans as “job-killing initiatives.” NRDC’s factsheet about HF notes that “some oil refiners have converted or begun converting from using HF to using newer and safer chemicals,” citing the phasing-out of HF at the CVR Wynnewood, OK, refinery and the Chevron Salt Lake City refinery. Parepally concluded by addressing the risks posed by transporting HF throughout the country, because nearly all HF in the U.S. is produced at one facility in Louisiana and travels by rail or truck to the 42 HF-using refineries across the U.S., imposing risk at every step of the way.

***

As the event came to a close, I could feel the crowd become more energized and more determined to find a path forward. Goldsmith expressed a similar sentiment after the event, recognizing that Waters’ bill has no immediate chance of passage given the current Republican trifecta in D.C. He asserted that the most promising path forward in the current political climate is to focus on litigation and advocacy with Attorney General Rob Bonta. Specifically, Goldsmith would like to investigate whether Attorney General Bonta would “tak[e] over” from the City of Torrance and “re-open” a 1990 Consent Decree between the Refinery and the City (negotiated by ExxonMobil and inherited by current owner PBF Energy) that is still in effect and arose from a public nuisance lawsuit. The Decree initially required the Refinery to dilute HF by 30% “with an additive that would make it less dangerous,” but the Refinery and the City agreed in the late 1990s to require only 10% of the additive (which, in any case, has never been proven effective) in a closed session of the City Council by a unanimous vote; the City has long declined to make documents from that closed meeting public. Goldsmith explained that the Decree requires a judicial finding that “HF is as safe or safer than the alternatives,” and asserted that if a judge revisited that finding and instead found that HF is less safe than the alternatives, a judge could invalidate the Decree.

Goldsmith stated that Attorney General Bonta’s office has communicated that they’d “like to do something” but haven’t identified what their preferred “legal pathway” is. However, Goldsmith is optimistic because Attorney General Bonta took “a very strong position on HF” in his letter to the Biden Administration EPA, signed by 19 other Attorneys General, concerning proposed regulations “on risk management plan rule improvements,” some of which involve HF. While the letter is unlikely to be acted upon during the Trump Administration, Goldsmith found it heartening that Attorney General Bonta spent 12 of the letter’s 70 pages discussing HF, which recognize that “neither the [Chemical Safety Board] nor the SCAQMD has received evidence that MHF is substantially safer than unmodified” HF. The letter asserted that the EPA had the authority to phase out HF and should do so: “the history of hydrofluoric acid releases and near-releases at refineries shows both that EPA can best drive the eventual phase out of hydrofluoric acid alkylation, but also that the groundwork is laid for EPA to take that action.” The letter did not comment on Attorney General Bonta’s authority or willingness to take action himself if the EPA failed to adopt these proposals, and did not mention whether he could or would reopen the Consent Decree between the City and the Refinery. Goldsmith also expressed hope that the litigation arising from NRDC, CBE, and the Clean Air Council’s recent petition arguing that HF poses an “unreasonable risk to human health and the environment” that is impermissible under TSCA may lead to court-ordered reforms and perhaps even an outright ban.

Goldsmith plans to renew TRAA’s advocacy for regulation from SCAQMD’s Governing Board, whose members have changed significantly since TRAA’s failed efforts in favor of Proposed Rule 1410. Only two of the Board members that voted in 2019 to adopt the voluntary agreements with the refineries instead of banning HF are still on the Board: Larry McCallon, appointed by the cities of San Bernardino County, and Vanessa Delgado, appointed by the Senate Rules Committee and serving as Chair. Goldsmith announced that TRAA will “analyze what we think the vote would be now and contact some of the new people” on the Board, and commented that he’d count reliable progressives like L.A. City Councilwoman Nithya Raman “as a yes” and has a particular interest in the “brand new” members, including Orange County Supervisor Donald P. Wagner, who replaced the corrupt former Supervisor Andrew Do.

Whether through legislation, regulation, or litigation, HF use at oil refineries should be banned outright, and after Saturday’s event, I feel energized and eager to organize in support of that goal. The “near miss” in 2015 should have been the wake-up call needed to ban HF. Unfortunately, it was not. Now, ten years later, South Bay and Harbor residents are still living in fear of environmental catastrophe, despite the recent proliferation of multiple viable alternatives to HF. Over the last decade, scientists have proven even more resoundingly that HF poses greater risks of death and grievous injury than its alternatives. Current industry conditions reflect that the Torrance Refinery and the Valero Wilmington Refinery—the only two out of fifteen refineries in California that still use HF—could convert to safer alternatives without suffering financial ruin. It’s long past time for those in power to recognize that, as Lyou said on Saturday, under the status quo, either “we need these refineries to operate perfectly”—which is unrealistic—“or they need to be lucky” because “ten years ago, we were really lucky” but we “don’t know if we’ll be as lucky if something comparable happens again.” Let’s not push our luck.

Reader Comments

One Reply to “Why Isn’t Hydrofluoric Acid Banned at Oil Refineries?”

Comments are closed.

Dave Lincoln and I have been publishing on the dangers of Hydrofluoric Acid refineries for over ten years. Dave and I had no luck persuading them to change, even though there is a non-threatening alternative available. We were able to persuade Dallin Oaks to force changes on two of the three refineries near Salt Lake City. However, nothing was published on the hideous threat these had presented. Dave’s site is LincolnsRiskRegistry.com. Our team is now in preproduction for a 2-Way interactive show series on the dangers. We estimate 7 Million casualties if both the Wilmington and Torrance refineries are hit. See 19minutes.com