The Animal Agriculture Industry Undermines Climate Action

Guest Contributor Alexander Wood, a UCLA Law student, writes that lessons learned from Big Oil can be applied to animal agriculture.

The case for decarbonization to address climate change is often, understandably, directed toward the fossil fuel industry. Public opinion toward the oil and gas industry has shifted in recent years, driven in part by public protests and litigation. Why hasn’t there been more movement against greenhouse gas emissions caused by animal agriculture?

Emissions from Animal Agriculture

It’s not for lack of research. The international scientific community has long known of the animal agriculture sector’s harmful contributions to climate change. A 2006 report titled Livestock’s Long Shadow produced by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) found that the animal agriculture sector is responsible for 18% of greenhouse gas emissions, more than that of the entire transportation sector. This is primarily due to deforestation and other land-use changes caused by converting wild areas into farmland to grow crops for livestock. Animal agriculture itself is responsible for 37% of anthropogenic methane, primarily from “enteric fermentation by ruminants,” or more colloquially, animal burps. These effects were further recognized in the 2022 Global Methane Assessment from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). This report found that animal agriculture emits approximately 115 megatons of methane per year, equaling the emissions of the entire fossil fuel sector.

In terms of CO₂ emissions reductions, a 2009 study from the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency found that shifting to a diet that includes just one serving of beef or pork per week and one serving of fish, poultry, or eggs per day can reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 10% compared to current dietary patterns. Furthermore, the study points out that by shifting to this low-meat diet, keeping temperature change under 2°C relative to pre-industrial levels becomes much cheaper.

Furthermore, a 2022 study from the World Wildlife Federation found that a shift toward healthier diets with an emphasis on more plant-based foods, while reducing food loss and waste globally, can increase mitigation by as much as 2.5 Gt CO₂ per year. For comparison, the International Energy Agency estimates that converting one-third of all vehicles on the road worldwide to fully electric would reduce emissions by only 2.0 Gt CO₂ per year.

Given the outsized effects transitioning towards plant-based diets could have, one may wonder why international climate policy has largely avoided this solution.

Institutional Capture

Critics have been vocal about the UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) failure to take animal agriculture emissions more seriously. A former FAO official, who spoke with Climate Home News on the condition of anonymity about his time with the organization, accused the FAO of “cherry picking” data to justify making recommendations on intensified animal agriculture systems. This official also pointed out that 11 contributors to the upcoming 2025 FAO report work for the International Animal Agriculture Research Institute, a group that, according to the former official, has been ideologically captured by the animal agriculture industry. The 2006 FAO report mentioned earlier, which criticized animal agriculture’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions, faced backlash from industry lobbyists and donors who pressured the FAO to change course.

Following this backlash from lobbyists and donors, the FAO gradually lowered its estimates of animal agriculture’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions in subsequent reports. Whereas the 2006 FAO report estimated animal agriculture accounted for 18% of global emissions, an FAO report in 2012 estimated it to be 14.5% and a 2023 report estimated it at 12% despite data showing a 39% rise in global meat production and an increase in livestock emissions of 14% between 2000-2014. Three of the academics whose research was used in the 2023 report went so far as to write a joint letter demanding that the FAO retract the report, with one saying, “I don’t understand why, with all the public trust [the FAO] ha[s], they would release reports without a methodology that justifies their authority. This is an institution with great power and influence, and it is not using it responsibly. To paraphrase my grandmother’s adage: ‘If you can’t produce something accurate, don’t produce anything at all.”

The draft 2025 FAO report now claims there is a “lack of consensus among scientists regarding the contribution of animal agriculture to global greenhouse gas emissions.” Shelby McClelland, of New York University’s Center for Environmental and Animal Protection, called this statement by the FAO “alarming” given their influence on agenda-setting for global climate action. Two scientists whose work was cited in the FAO’s 2025 report publicly called for its retraction, stating that it seriously misrepresented their research and underestimated the climate benefits of dietary change by a factor of up to 40.

Analogies to Other Industries

Researchers have compared the animal agriculture industry’s response to evidence that their products cause climate change to that of the fossil fuel industry. Meat and dairy companies have lobbied against climate policies and supported organizations working to delay consensus and policy action on climate change. The animal agriculture industry has followed the example set by fossil fuel companies attempting to influence policy and funded universities with the aim of influencing climate change research. Just as the fossil fuel industry promoted doubt about human-caused climate change, so too has the animal agriculture industry funded scientists to publicly question or discredit studies linking animal agriculture to climate change. Internal documents from the University of California obtained by The New York Times show that the CLEAR Center at UC Davis, now a leading voice on agriculture and climate, receives nearly all its funding from industry donations and collaborates on messaging with the American Feed Industry Association (AFIA), a major livestock lobbying group. The CLEAR center was established in 2019 with a $2.9 million multi-year gift from the Institute for Feed Education and Research (IFeeder), the nonprofit arm of the AFIA. CLEAR Center director Frank Mitloehner has received at least $5.5 million directly from the animal agriculture industry, according to his 2021 CV.

Since receiving industry funding, Mitloehner has been promoted by the dairy industry as “the scientist setting the record straight on cows and climate change.” He has authored white papers that have led to the exclusion of reduced meat consumption and environmental criteria from US dietary guidelines. He has testified before Congress and met with world leaders to downplay the effect the animal agriculture industry has on greenhouse gas emissions. An internal memo obtained by the New York Times shows that IFeeder viewed Mitloehner as a powerful scientific spokesperson, describing him as a “neutral, credible, third-party voice” who could “show consumers that they can feel good” about eating meat. The CLEAR Center’s messaging, it said, would help counter a “small but vocal minority with hidden agendas,” including celebrities and policymakers, damaging the public image of meat.

Mitloehner has denied any industry influence, claiming it was “absolutely not correct” that the center provides communications services for the livestock sector and insisting that “what we communicate is rooted in research and science — always.” Mitloehner has dismissed the idea that dietary change meaningfully affects the environment, calling it “a myth” in his 2019 Congressional testimony. Yet this is belied by myriad studies including a report published in the journal Science, which found that moving from current diets to a diet that excludes animal products has the potential to reduce diet-related greenhouse gas emissions by 49%.

Lessons from the Fight Against Fossil Fuel

By sowing doubt about the human causes of climate change, the fossil fuel industry delayed the shift of public sentiment towards greener energy sources. However, sentiment has indeed begun to change.

Over the past several decades, climate activists, researchers and policymakers have created a shift in public opinion in support of green energy and against the use of fossil fuels. For example, a 2015 investigation revealed that Exxon had known about climate change since at least July 1977, yet spent millions in the following decades to spread misinformation and cast doubt on the science of climate change. Once this information became public, the hashtag #ExxonKnew trended on social media. Additionally, four state attorneys general launched investigations into Exxon for fraud related to climate change denial.

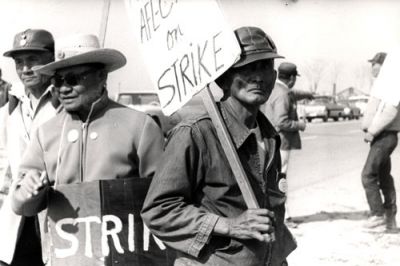

Much of the fight against fossil fuel’s influence has come from younger generations, through both public protests and legal challenges. In 2019, Greta Thunberg famously spoke at the United Nations accusing world leaders and policymakers of stealing the future of young people and galvanizing a youth movement. Like most social movements, the international fight against animal agriculture is likely to come from young people. In the same way Thunberg introduced real emotion to the fight against fossil fuel, perhaps we are approaching a time when that same emotional urgency is brought to the fight against animal agriculture.

If just a fraction of those focusing on the (very valid) fight against the fossil fuel industry shifted their research and activism towards animal agriculture, we could start to see a major change in public sentiment. This article alone provides data and talking points to spur more interest in the field. There is no doubt the benefits in reducing animal agriculture rival those in reducing our reliance on fossil fuels.

Guest Contributor Alexander Wood is a rising 2L at UCLA School of Law.

Reader Comments

One Reply to “The Animal Agriculture Industry Undermines Climate Action”

Comments are closed.

This seems like a particularly tricky area for change. Those holding up animal ag have shown a remarkable and persistent willingness to close their eyes to the implications of their diet preferences—i.e., very literally, “how the sausage is made.” Sure, fossil fuels have their enthusiasts, too, but their motivations just aren’t as visceral. I think any major change in this area is going to require more than modest increases in research or activism.

Those plant-based alternatives keep getting better, though….