One Easy Fix to Prepare for the Next Big Disaster

A little-known drafting wrinkle in current state law is impeding local governments from springing into action after disasters.

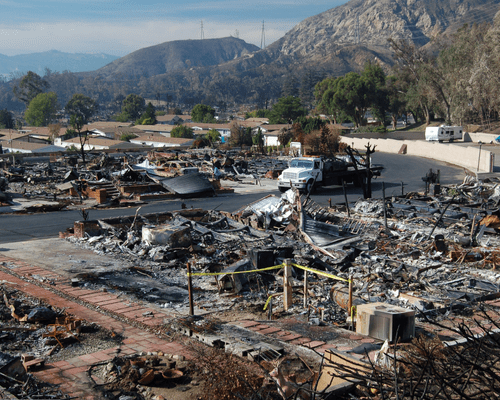

Along with my fellow Angelenos, this year I’ve had a front-row seat to the challenges of regional recovery from a major disaster event. The January 2025 Eaton and Palisades wildfires devastated LA-area communities, including two—the Palisades and Altadena—locally renowned for their distinctive neighborhood feel. In the aftermath, the response highlighted challenges at every level of government, from concerns about the adequacy of federal cleanup efforts to local political controversy about preparedness and response. Almost 10 months after the fire, some are beginning to rebuild in the affected areas, but many continue to navigate a complicated maze of government and insurance processes without certainty about their ability to return to the neighborhoods they once called home. While this rebuilding process is inevitably complicated, there is one relatively easy thing California could do now to be better prepared to recover from the next big disaster.

I know because I spent the first half of the year as part of a UCLA research team working to support the Blue Ribbon Commission on Climate Action and Fire-Safe Recovery, a group of experts convened by County Supervisor Lindsey Horvath to consider ways the region could recover from the January fires not only expediently, but with a mind to survivability in future disaster events that we’ll most certainly face in our climate change-impacted and earthquake-prone region.

The Commission issued a number of important recommendations; you can read more about those here. Key among them were a core set that recognized how critical well-executed government response is after a disaster event. The Commission did its best to propose a governance structure that could holistically manage the recovery, increasing accessibility and accountability to community members and taking advantage of financing structures and economies of scale to deliver resiliently rebuilt neighborhoods displaced residents could return to. That proposal made its way into state legislation that was ultimately sidelined after intense backlash driven in part by former reality TV star Spencer Pratt, a sentence I never thought I’d write.

While the Commission’s proposal was a good idea, the implementation challenges highlighted a real problem: It’s very, very, very hard to start the process of thinking about how to manage disaster recovery in real time during the response. Governments need tools to be able to plan ahead—especially since one thing we can be sure of is that California communities will be faced with other major disaster events in the future.

California legislators recognized this decades ago. Following a catastrophic 1985 earthquake in Mexico City, the California Legislature passed the Disaster Recovery Reconstruction Act (DRRA) of 1986, Cal. Gov. Code §§ 8877.1 et seq., with the specific aim of giving local governments the tools to proactively plan for disaster, including setting up governmental entities ahead of time that would be waiting in the wings, ready to effectively manage disaster response and recovery when the time came. These “reconstruction authorities,” if created by local governments, could have the powers the Blue Ribbon Commission concluded would be critical to effective recovery: tax-increment financing authority to fund rebuilding efforts; the ability to purchase and hold property to avoid land speculation; the authority to enter into contracts, enabling bulk purchasing of materials and large-scale rebuilding agreements; and the ability to sell property, providing a pathway for a “right of first negotiation” for displaced residents returning to the neighborhood.

So why aren’t California’s local governments taking advantage of this power?

One reason is that a drafting wrinkle in current state law is impeding them. All of those powers I described above were once held by a class of government agencies called community redevelopment agencies, or CRAs, a type of agency created by state law in the mid-1940s to promote the redevelopment of “blighted” property in urban areas. CRAs were controversial, and they were ultimately dissolved in 2011 through the enactment of two bills, AB x1 26 and AB x1 27. In February 2012, the State of California ceased operating CRAs, and successor agencies were created to wind down their obligations and activities.

One reason is that a drafting wrinkle in current state law is impeding them. All of those powers I described above were once held by a class of government agencies called community redevelopment agencies, or CRAs, a type of agency created by state law in the mid-1940s to promote the redevelopment of “blighted” property in urban areas. CRAs were controversial, and they were ultimately dissolved in 2011 through the enactment of two bills, AB x1 26 and AB x1 27. In February 2012, the State of California ceased operating CRAs, and successor agencies were created to wind down their obligations and activities.

But the DRRA was passed when the CRAs still existed, and so instead of spelling out the individual powers a municipally-created “reconstruction authority” could possess, it simply references the CRAs: Under the law, reconstruction authorities can have “powers parallel to a community redevelopment agency, except that the reconstruction authority would be authorized to operate beyond the confines of designated redevelopment areas and would have financing sources other than tax increment sources.” Cal. Gov. Code § 8877.5.

The problem? Now that CRAs are no longer authorized by law, the powers a reconstruction authority could have are called into question. California courts have held that where, like here, a reference to a previously-enacted statute is general, the referring statute is impacted by changes to the previously-enacted statute. That means that even if local governments tried to proactively create a reconstruction authority with the kinds of powers I outlined above, a court could find that the dissolution of the CRAs leaves reconstruction authorities with none of those powers. Critically, even absent an unfavorable court decision, uncertainty about the scope of a reconstruction authority’s powers could significantly impair its ability to secure the financing needed to effectively facilitate recovery efforts.

The good news is that there’s an easy fix: The Legislature could amend the DRRA to specifically enumerate the types of powers a reconstruction authority could possess. And while they’re at it, they could also inject an incentive scheme for locals to start engaging in proactive planning processes by making access to certain government funds contingent on getting a recovery structure in place.

I think often about how different the post-fire recovery process here in Los Angeles could have looked if we had a local disaster recovery agency at the ready: a single point of contact for fire-impacted communities that could act quickly and at scale to facilitate rebuilding. I think about how much more resilient to fire communities are when they plan at a neighborhood scale, rather than property by property, and about the already lost opportunities to rebuild at that scale. And I think about all the California neighborhoods still standing at the edge of the wildland-urban interface, vulnerable to the next wildfire turned urban conflagration—and how important it is that next time, we do better.

Reader Comments

3 Replies to “One Easy Fix to Prepare for the Next Big Disaster”

Comments are closed.

There are some good ideas in your report.

Yet, please recognize that trust is lacking. For one thing, I don’t miss the CRAs at all.

Is it not true that the state wanted to shove in a bunch more density into the burn areas?

If it wasn’t true, why was a specific exemption needed? (I think for sb9. I don’t really recall. The Cali Dems pass soooooooo much yimby legislation, it is numbing.)

It is bad enough that people lost their homes. But to be subject to yimby machinations in this way is so sad. And there is no way I would ever support giving yimby supporters – a group which includes pretty much all people in power in this state now – even more power. That is a non-starter.

Whereas, helping people at all income levels to build greener and more resilient buildings seems like a no-brainer.

Too bad the existing yimby laws made this so unpalatable.

But, whose fault is that?

The array of so-called solutions – whether called Redevelopment Authorities Version 2, SB 782 Climate Resilience Districts, Enhanced Infrastructure Financing districts, AB 797 bank CRA financing, or something else – all seem to miss the fact that firestorms, earthquakes & other disasters can do significant harm to both incorporated municipalities and urbanized unincorporated communities. The former have Mayors and City Councils to focus on rebuilding, but the latter have to rely on county Boards of Supervisors who, frankly, are not up to the job. Since 5-6 MILLION Californians live in those urbanized, unincorporated communities, that’s not a trivial distinction. The plight of those 5-6 million Californians is made worse by state policies that work against local control and thus stymie rebuilding and restoration.

If you got burned out, California (un)Incorporated, you certainly have my sympathy.

And I could easily think that a fire aftermath could be a bad time to have to rely on one representative.

I also agree that lately, the state legislature seems bent on making our lives worse – while calling it “progress.” I’m not a fan of them, generally.

Having said that, the details do matter. On an overall basis, I’m not sure there would be an advantage to be incorporated v. unincorporated. Maybe people in unincorporated areas get left alone more, the rest of the time? I don’t know – but I think it’s possible. And maybe some counties are better than others – that seems likely.

And, maybe that one supervisor will do a good job. That *could* happen too.

And on the flip side, supposing that we ever get rid of these state mandates – that might be nice, but I’m not sure it would help the city of LA one bit! Because the City Council will probably still be bleeped.

People who live in LA have about the same amount of control over the quality of their daily lives as a person in China. At least, it often feels that way. (No disrespect meant to the people of China.) Their only real recourse is generally a lawsuit. That is the only time when I see anyone listen to regular people here. We are not on the radar.

However, I should probably try not to sound ungrateful. It is all just the vagaries of self-government, I suppose. (?)