A New Era of Conservation on the Horizon

Lessons from philanthropist and conservationist Kris Tompkins after a visit to the UCLA Emmett Institute.

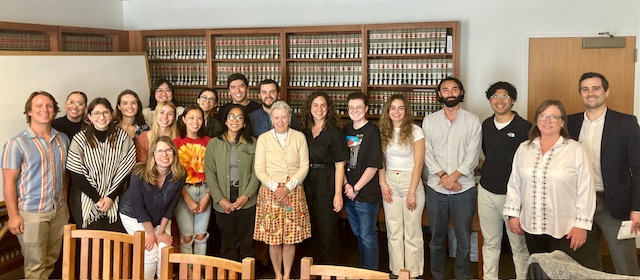

“Sentiment without action is the ruin of the soul.” That line by writer Edward Abbey is a favorite quote of Kris Tompkins. She’s the legendary conservationist and philanthropist who recently visited UCLA Law at the invitation of the Emmett Institute and the Lowell Milken Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofits.

Ever since Thompkins’s visit with our staff and students, I have been thinking about the uncertain future of conservation in the context of climate change. Climate action will require sacrifices that may harm conservation goals. Therefore, defining and protecting the ecosystems we cannot afford to lose becomes a pressing issue.

Luckily, Kris Tompkins’s story continues to inspire new generations of conservationists who now seek innovative legal, political, and financial means to achieve the goals that Kris and Douglas Tompkins set decades ago: protecting natural beauty by creating national parks. This example came into sharp focus this month when news broke that several newer organizations are buying a swatch of land known as the Chilean Yosemite for conservation.

A Life Dedicated to Beauty

Kris Tompkins was one of Patagonia’s first employees, rising to become the company’s CEO, a position she held for over 20 years. Her husband, Douglas Tompkins (1943-2015), was a multi-millionaire entrepreneur and founder of The North Face and Esprit.

However, in Kris’s words, they realized that the pinnacle of the American corporate world was not the dream they were longing for; something was missing. Driven by this discomfort, in the early 1990s, Kris and Doug left everything behind. They resigned, sold their shares, and moved to Pumalín in the Chilean Patagonia, a cold and isolated fjord between glaciers and primary forests. From this remote place, they initiated one of history’s most ambitious conservation projects.

To date, Kris and Doug’s efforts have resulted in the creation of over 15 million acres of protected areas—an area larger than Switzerland, The Netherlands, or Belgium.

However, dedicating a life to conservation is the opposite of a peaceful retirement. The notion of two American millionaires buying vast amounts of land, considered inhospitable or of little value, was met with suspicion by many Chileans. People wondered, “What are these gringos doing here? Are they splitting the country in two? What are their real intentions?”

In 1990s Chile, philanthropy was unfamiliar; the focus was on growth, and society viewed any non-profit-driven movement as suspicious. Politicians of the time tried everything to stop the Americans with their “murky” intentions.

But the Tompkins persisted and acted on their sentiments. Even during the most challenging times, they consistently declared that their sole purpose for buying land was to preserve Patagonia’s natural beauty and turn those areas into national parks for all Chileans. They believed national parks are democratic tools that belong to everyone.

When the Tompkins opened Pumalín Park to the public, perceptions changed. Chileans began to believe in the Tompkins’ vision, realizing the treasure hidden in their backyard. The Tompkins went from being viewed as suspicious gringos to role models for a generation. Politicians shifted from opposing them to boasting about their support. Douglas Tompkins was a local legend.

Tragedy and a new beginning

In December of 2015, Doug’s kayak capsized while he was paddling on Lake General Carrera’s icy and unpredictable waters in Chilean Patagonia with friends, including Yvon Chouinard, Patagonia’s founder. After a few hours, Douglas Tompkins died of hypothermia, in his law, in his place. Following Doug’s death, Kris did what they’ve always said they would: she donated the land to the State of Chile, with the condition that all of Tompkins’s properties were designated national parks. This donation resulted in the creation of more than 12 national parks in Chile and Argentina.

Kris’s organizations continued to work in Patagonia and the Argentine wetlands, focusing on “rewilding,” which refers to helping nature heal, giving space back to wildlife and returning wildlife back to the land, as well as to the seas. This effort involved removing thousands of miles of barbed wire and reintroducing iconic species like the puma, anteater, and jaguar.

Rewilding Chile, and Rewildling Argentina are now independent organizations designed to be run by others to live on after her. The rewilding mission will continue.

But that is not all: just before she visited UCLA Law this spring, Kris met with Chile’s President, Gabriel Boric, to finalize the donation of critical pieces of land, soon to be declared Cabo Forward National Park.

Kris and Doug’s passion and determination changed how Chileans perceive conservation. Protecting the environment evolved from being seen as a luxury for hippies to a fundamental aspect of national identity.

Following the Example

A few weeks ago, several organizations committed to buying one of the most iconic lands in Chilean Patagonia, the Cochamó Valley, known as the Chilean Yosemite, for its giant granite walls. This initiative aims to connect this valley with what is now called “Route of the Parks of Patagonia”, a large corridor of more than 28 million acres of national parks, including the ones donated by the Tompkins. Many involved in this initiative were former collaborators of Tompkins Conservation, who are now honoring its legacy and inspiration.

The challenge is to achieve conservation goals without the kind of financial backing the Tompkins enjoyed. Due to the costs of land and the political difficulties, it is imperative to look beyond the model of a heroic attempt by a single visionary. Modern conservation initiatives require a solid collaborative effort.

With this in mind, several entities are collaborating to conserve Cochamó through a sort of conservation crowdfunding involving Chilean and international organizations like The Nature Conservancy, Freiya, Wyss, and Patagonia Co., which formed the alliance called “Conserva Pucheguin,” led by the local NGO Puelo Patagonia.

After decades of fighting, Conserva Pucheguin signed an agreement to purchase the Pucheguin Ranch for $63 million within a certain period. Conserva Pucheguin is now working to raise the money from international and Chilean donors; to date, it has raised more than $15 million. Unlike Tompkins’s efforts in the nineties, the Chilean philanthropists are now playing an active role in this effort.

The environmental world is closely watching this pioneering model as it opens possibilities for new conservation initiatives.

We need to keep fighting for conservation

UCLA Law was lucky to have Kris Tompkins sharing her story, projects, and dreams with the community.

If I had to choose just one of Kris’ thoughts, it would be the relevance of beauty in our lives—beauty as a subject of rights, as a driving force. Beauty makes us human, and we are the only ones who can protect it. Although conservation has always been at the heart of environmentalism, the emphasis has reasonably shifted to climate action. My UCLA Law colleague Prof. Jim Salzman et al. note, the tension between climate action and conservation is growing. Meeting climate goals will require more resources, power generation, and transmission, necessitating significant sacrifices.

Undoubtedly, the world needs to engage fully in climate action, but it is equally imperative to do it right so we do not destroy what we want to protect in the first place. Climate change demands immediate action to keep the planet habitable, but we need much more than a future where we can exist.

Nature must be protected because it has intrinsic value but is also crucial for humanity. Humanity survives because of the air it breathes but thrives on the beauty that surrounds it. If the climate allows, thanks to Kris and Doug Tompkins’ work, humanity will have a small sanctuary of wilderness and beauty for the sake of nature, ours, and future generations.

Reader Comments