Manila Protests Over Environment Follow a Rich Tradition

Happy Filipino American History Month. Here’s a look at Filipino-led protests for environmental justice.

The Philippines made international news last month when several tens of thousands of protestors took over the streets of Manila to express their outrage over the government’s embezzlement of over a trillion Philippine pesos (approximately $17.6 billion USD) designated for flood control projects. Losing this amount of climate-designated funds to corruption would be problematic anywhere in the world, but it is particularly impactful in the Philippines, where the government already lacks the resources to cover the costs of the climate disasters that are now a regular occurrence. A 2022 World Bank report projected that the Philippines could lose as much as 7.6% of its GDP by 2030 due to climate change. This is because, like most countries in the Global South, although the Philippines has done little to contribute to climate change, it is bearing a disproportionate brunt of climate change’s effects. Indeed, Super Typhoon Nando—only one of the approximately 20 typhoons the Philippines will experience this year—made landfall the day after the protests, causing massive landslides and flooding.

It may therefore be unsurprising that this recent protest was not the first example of Filipino climate activism—Filipinos and Filipino-Americans have been organizing for environmental justice for decades. Examining previous Filipino-led protests for environmental justice seems like a good way to mark Filipino American History Month — and my inaugural Legal Planet post. I’m an environmental justice attorney and the new Shapiro Fellow in Environmental Law and Policy at the UCLA Emmett Institute. I am especially interested in the intersection of environmental justice and the labor movement.

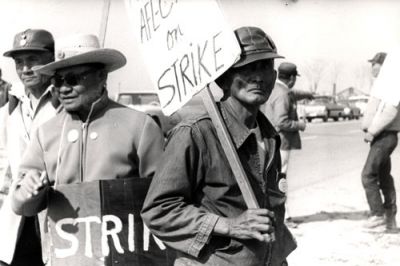

The most well-known, but still often overlooked, Filipino-American led environmental justice movement began on September 8, 1965, when over 800 Filipino farmworkers affiliated with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC), led by Larry Itliong, struck 10 grape vineyards around Delano, California. A little over a week later, the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA)—led by Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez—joined the strike, and the Delano Grape Strike, one of the most significant labor struggles in U.S. history, was born.

Contrary to popular knowledge, however, the Delano Grape Strike was not only a fight for higher wages—it also was a fight for environmental justice. In fact, the United Farm Workers (UFW), which formed from the joining together of AWOC and NFWA, was the first labor union in the country to advocate for environmental justice. The farmworkers demanded regulation of the use of harmful pesticides and fertilizers in the fields, as exposure to these chemicals was causing disproportionate rates of cancer, birth defects, and other severe health issues in their communities. In addition to striking, the farmworkers organized a very successful national consumer grape boycott. Their activism was not without opposition. The strikers faced mass arrests, intimidation, and violence such as being sprayed with pesticides while on the picket line. But after five long years of strikes and demonstrations, in 1970, a collective bargaining agreement that included better pay and protections against pesticides was finally signed.

Meanwhile, over 7,000 miles away, Bai Bibyaon Ligkayan Bigkay—the first woman chieftain of the Talaingod-Manobo tribe—was beginning to rise to prominence for her resistance against the logging industry. In the 1980s and 1990s, the logging company Alcantara and Sons, or “Alsons,” set its sights on the old growth rainforest of the Pantaron Mountain Range. The Pantaron Mountain Range is the ancestral land and home of the Lumad people of Mindanao, a group comprised of the Talaingod-Manobo tribe and 17 other tribes. After Alsons refused to heed the Lumad’s many warnings to vacate their lands, Bai Bibyaon united, empowered, and rallied all 18 tribes to stand up against the loggers. Together, the Lumad people launched a pangayaw, a traditional Lumad call to arms to defend their community, resources, and ancestral lands. Led by Bai Bibyaon and united as one, the Lumad successfully kicked out Alsons and protected their home from further destruction.

As Bai Bibyaon continued to grow into her role as the “Mother of the Lumads,” the environmental justice movement began gaining real traction in the Filipino-American community. In 2000, a group of Filipino-Americans founded the Filipino/American Coalition for Environmental Solidarity (FACES) to draw attention to, and demand reparations for, the “toxic legacy” left by the Unites States and its military bases in the Philippines. Through fighting for climate justice, providing nature-based education, strengthening transnational relationships, and prioritizing cultural care and Indigenous solidarity, FACES takes on environmental justice issues that impact Filipino communities here in the U.S. and in the Philippines.

One of FACES’ most prominent campaigns was its CAREnow! campaign pressuring Chevron, Shell, and Petron to close their 89-acre oil depot in Manila’s Pandacan district and compensate the area’s residents for the depot’s damages to their health. Based in the San Francisco Bay Area, FACES organized protests at Chevron’s headquarters, which were in San Ramon at the time. FACES worked in solidarity with Advocates for Environmental & Social Justice (AESJ), an activist organization in Pandacan, to bring America’s attention to the depot’s harms to the environment and public health. Much of the groups’ work on this campaign, however, took place years after the mayor of Manila had already ordered that the depot be closed and relocated.

The corporations were first ordered to close the oil depot in 2002, but it was not until 2015—after over a decade’s-worth of drawn-out litigation and delay tactics—that the oil depot finally started shutting down. Fortunately, FACES, AESJ, and the other grassroots groups never lost sight of their mission.

Today, as groups like the Philippine Movement for Climate Justice continue the battle to hold big polluters accountable and protect the environment, some scholars have started to study some of the reasons why exactly there is such a rich history of Filipino and Filipino-American environmental justice activism. In response, many have highlighted the connections between traditional Filipino values such as pakikisama, utang na loob, and kapwa and environmental justice principles. These terms are not easily translated, but they emphasize mutual care, community, and solidarity—all values that are both embedded in Filipino culture and critical to the work we do as environmental justice advocates. As a Filipino-American, I hope our community remains guided by these values and the Filipino and Filipino-American environmental justice advocates that came before us. Isang bagsak.

Reader Comments