Sackett and the Dangers of a New ‘Clear-Statement Rule’

The Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. EPA will be bad for the nation’s wetlands. It is just as bad for democracy.

The Supreme Court decision in Sackett v. EPA limits the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to defend a large portion of the nation’s wetlands and waterways from pollution. The decision strips key environmental protections from the Clean Water Act by narrowly defining which bodies of water can be regulated under the Act, making it the most important water-related case in decades. But this decision is about more than wetlands and water.

As recounted here by Richard Frank, the Sacketts sued the EPA in 2008 after they sought to build a house in Idaho near Priest Lake and the agency said they needed a permit under the Clean Water Act because the wetlands were federally protected. The couple argued that if a wetland doesn’t feature “a continuous surface connection” to a navigable waterway, there is no such federal requirement. In the majority opinion, Justice Samuel Alito writes that the Clean Water Act “extends to only those wetlands with a continuous surface connection to bodies that are ‘waters of the United States’ in their own right,’ so that they are ‘indistinguishable’ from those waters.” The justices unanimously agreed on the judgment that the Sacketts should not have been subject to EPA authority, but there was stark disagreement over the majority’s reasoning for how to define the waters of the United States. The concurring opinions say a lot about where the court is headed on environmental rulemaking and beyond. It shows the conservative majority is intent on finding new ways to override, rather than defer, to agency authority in general.

I put some questions about the importance of the decision to the UCLA Emmett Institute’s Cara Horowitz and Julia Stein.

Q: What does the Sackett v. EPA decision mean for enforcement of the Clean Water Act?

Cara Horowitz: The Court bends over backwards to shrink the reach of the Clean Water Act significantly, so that it will no longer protect many wetlands and perhaps other waters that have been a core part of the statutory scheme for many decades. This will make it much harder for the federal government to protect water quality—and surely this is the Court’s goal. The opinion is clear in its aim to shift more power to the 50 states to control water pollution, with the likely effect of creating “red state” and “blue state” approaches to water protection.

Q: This decision follows a similar curtailment of EPA authority from last term in the West Virginia v. EPA case, having to do with regulating air pollution. Taken together, what is the future of environmental regulations?

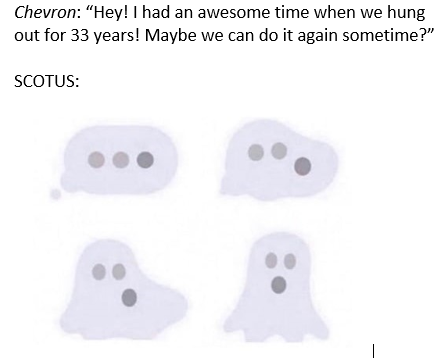

Julia Stein: One of the most notable features of this decision was the Court’s articulation of what seems to be a new “clear-statement rule”—similar to the “major questions” doctrine we’ve seen emerge over the past few terms—that requires Congress to “enact exceedingly clear language” in circumstances involving the regulation of private property. Here, the Court seems to be adding to a list of circumstances under which it feels entitled to second-guess Congress’ delegation of its authority to executive branch agencies. This builds on the Court’s recent pattern of ghosting Chevron deference, which the Court has historically applied to questions involving exercise of agency authority like the one here.

JS: In other words, this newly-articulated clear-statement rule removes this case from the Chevron framework entirely, creating an opportunity for the Court to override agency judgment rather than deferring to it. Taken together with West Virginia v. EPA, this decision seems to portend increasingly serious constraints on federal environmental regulation; agency rules seem likely to find themselves in the danger zone if they don’t cleave carefully to the express letter of a statute—and sometimes even when they do.

Also notable to me was Justice Thomas’ concurrence railing against the application of, in his view, an overly-broad interpretation of the Commerce Clause to allow intrastate regulation by federal agencies, particularly in the environmental law space. While I don’t think his view is shared by even a majority of the conservative justices, coming as it does on the heels of the decision in National Pork Producers Council, which examined the extent of application of the dormant Commerce Clause, his concurrence does signal an ongoing interest by at least a portion of the Court in revisiting longstanding Commerce Clause principles.

CH: Yes to what Julia said (and I’ll also note how much I like the phrase “ghosting Chevron”). This decision is consistent with—and expands—the general trend of this Court to shift power to itself at the expense of expert agencies. Folks sometimes complain that agencies are unelected bureaucrats who should not be making important policy decisions, but even if you agree with that critique (which I don’t), the Supreme Court is both significantly less politically accountable, and significantly less expert, than agencies. So, this trend is likely to result in less well-informed outcomes that accord less well with democratic norms and preferences.

Q: Do you think the court’s conservative majority is effectively rolling back the authority of Congress when it comes to writing legislation that is the basis for important environmental regulations?

JS: The clear-statement rule articulated by this opinion is quite stunning, because it doesn’t seem to stop at curtailing executive branch agency authority. Unlike the “major questions” doctrine, which is really about how clear Congress needs to be when it delegates lawmaking authority to agencies, this new clear-statement rule says Congress needs to be extra-clear if it wants to legislate at all in ways that could impact private property, including about “land and water use,” which the Court says are at “the core of traditional state authority.” This takes lots of settled ideas about our federalist system and turns them on their head, chief among them the idea that Congress, as the body with the closest ties to the electorate, should have primary lawmaking authority, to be curtailed by the Court only when exercised in violation of Constitutional principles.

As best I can tell, the majority seems to be conferring upon itself the sole authority to determine whether or not Congress was, in its view, clear enough and, if not, then the Court gets to decide what the law should be. Sackett itself provides a pretty grim picture of how this can play out because, as conservative and liberal justices alike point out in the “concurrences,” Congress actually was rather clear in the Clean Water Act, and it’s Alito’s opinion that’s having to do a lot of contorting to inject vagueness where there doesn’t appear to be any in the statutory text. But if the Court can maneuver its way to manufactured ambiguity here, and then use that to override Congressional judgment, it’s hard to see where the Court won’t be able to do that—if it wants to.

Q: Speaking of the concurrences, the three liberals joined by Justice Kavanaugh disagreed with the majority’s reasoning. What’s most notable about Justice Kagan’s sharply worded opinion?

CH: Justice Kagan calls out what she sees as her colleagues’ deceptive use of the so-called “clear statement” rule to substitute their own preferences for those of Congress, even where Congress has been clear in its direction to agencies. She writes, “Clear statement rules operate (when they operate) to resolve problems of ambiguity and vagueness. And no such problems are evident here. [This] congressional judgment is as clear as clear can be—which is to say, as clear as language gets. And so a clear-statement rule must leave it alone. The majority concludes otherwise because it is using its thumb not to resolve ambiguity or clarify vagueness, but instead to “correct” breadth.” She also rightfully emphasizes that “the Court’s appointment of itself as the national decision-maker on environmental policy” will make it harder to keep our nation’s waters clean.

JS: I think it’s also worth mentioning that Justice Kavanaugh—a conservative member of the Court—wrote separately (joined by the three liberal justices) to criticize Justice Alito’s misreading of the Clean Water Act’s reach. He did so primarily to point out that “the Court’s new test will leave some long-regulated adjacent wetlands no longer covered by the Clean Water Act,” but in suggesting he’d “stick to the text” of the Clean Water Act in determining which wetlands are protected, he echoes Justice Kagan’s conclusion that the Court is stepping in to rewrite a law that is, on its face, clear, but just means something different than the Court wants it to.

Q: West Virginia v. EPA had a connection to the global climate crisis. Sackett would appear to be a narrower case because it’s about protecting smaller waterways and wetlands. Why might it be wrong to underestimate the reach of this decision?

CH: I’ll push back a bit on the characterization of this decision as affecting only “smaller” waterways and wetlands. We don’t know yet exactly which waters and wetlands this strips of Clean Water Act jurisdiction, but it’s certainly not only small ones. Many very large wetlands will be affected, with cumulatively hugely important consequences—some estimate that nearly half the country’s wetland areas will be left uncovered. And there are many large, important waterways in the West, for example, that don’t fit what appears to be the Court’s conception of permanent, continuously flowing rivers and streams, because the West’s hydrology is often seasonal. Think of the L.A. River, for example, or of Tulare Lake, which only periodically appears after heavy snowfalls, as it is doing in the California central valley right now. This decision brings the status of those kinds of waterways into question, even though they are certainly significant hydrologically, commercially, culturally, and otherwise.

JS: In addition to the serious environmental consequences we’ve discussed, this decision portends some choppy waters ahead for the traditional balance of powers between the three branches of our government. The reemergence of the “major questions” doctrine—and the long decline of Chevron deference before that—already signaled the Court’s desire to wrest power from the administrative state. But now the Court seems to have set its sights directly on Congress, too.

Reader Comments