Want to Fight for Science? Look to South Dakota. No, Really.

We need a permanent grassroots strategy for science before we are buried in Idiocracy.

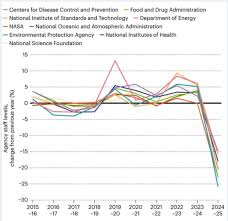

Nature this week offers a series of terrifying, interactive graphs detailing the Trump Administration’s Idiocratic War on Science. Not only has it butchered federal scientific research grants, but as you can see in this graphic, it has hollowed out the federal scientific workforce – the dedicated professionals who develop data to allow for science-informed policy in the first place, and monitor and audit the grants to make sure that they do what they are supposed to.

Nature this week offers a series of terrifying, interactive graphs detailing the Trump Administration’s Idiocratic War on Science. Not only has it butchered federal scientific research grants, but as you can see in this graphic, it has hollowed out the federal scientific workforce – the dedicated professionals who develop data to allow for science-informed policy in the first place, and monitor and audit the grants to make sure that they do what they are supposed to.

As I mentioned last week, Congress appears to have blocked the Regime attempts to strangle scientific agencies through funding cuts, but even here – assuming that the Supreme Court does not allow Russ Vought to impound the money – but even here, as Science reports:

Trump has redefined what success means, given that Congress accepted some cuts and has declined to challenge many of his policy changes, such as gutting global health programs and altering guidelines for childhood vaccines. “People are celebrating things that not that long ago would have been seen as defeats,” says a congressional aide who is not authorized to speak on the record and works for a Democrat. “That’s frustrating.”

That Science story reports on what it deems to be more aggressive attempts from some in the science community to fight back. The most straightforward are the political action committees that seek to support pro-science legislators, although one primary beneficiary of largesse – Maine’s Susan Collins – indicates that the directors of these PACs do not fully understand how only a Democratic takeover of Congress can truly create sustainable and necessary funding levels.

The others I confess seem to me more cosmetic.

One researcher, frustrated by what she saw as the research establishment’s tepid and outmoded response to Trump, has launched an entirely new group that is taking a more activist—even theatrical—approach. “Stodgy” science advocacy groups have clung to “tactics that haven’t kept up with the times. … These are people who are still bringing white papers to a gunfight,” says Colette Delawalla, a doctoral student in psychology at Emory University and founder of Stand Up for Science, which has delivered rubber ducks to lawmakers as part of an Impeach the Quack campaign to oust Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and placed ads on the gay dating site Grindr to help elect Democrats to Congress.

I admit that this wins points for performance, but what exactly does it to protect science? Twitter is not real life, and I am unsure whether this builds power.

In a crisis like this, it is churlish to criticize those who are actually fighting the fight, and more power to them. But it seems to me that, in the words of Prime Minister Mark Carney’s brilliant Davos speech: we are in the midst not of a transition, but a rupture. And that will require even bigger political strategies.

Even were there to be free and fair elections, and the Democrats return to power in 2028, we have learned that the disease in the American electorate is deep. American voters gave Donald Trump a second term in 2024 – after January 6th, after he killed hundreds of thousands with his criminally negligent response to COVID, after he was indicted for serious crimes and convicted for felonies. And they did so with a plurality, unlike in 2016. They also gave Republicans majorities in Congress (even though in the House this was accomplished only by gerrymandering). In other words, even a return to sane governance will not change the long-term anti-Science trend until and unless the electorate can be persuaded to stop it. And that change cannot be accomplished with campaign contributions, or marches, or protests. Those things mobilize those sectors of public opinion that can stand for Science. But they cannot alter opinions in and of themselves. That is different work.

Which brings me to South Dakota.

Many years ago, during what is now known as the Second Intifada, I went on a solidarity trip to Israel, then suffering from daily suicide bombings, as part of a group with American Jewish Committee (which for the record I no longer belong to). One man I met was a Republican Jewish activist from the Mount Rushmore State, Stan Adelstein, well known in political circles as “that Jew from South Dakota.” We hit it off, and he talked to me about doing grassroots lobbying. 36-year-old me didn’t know much about what he meant. So he told me a story.

Many years ago, during what is now known as the Second Intifada, I went on a solidarity trip to Israel, then suffering from daily suicide bombings, as part of a group with American Jewish Committee (which for the record I no longer belong to). One man I met was a Republican Jewish activist from the Mount Rushmore State, Stan Adelstein, well known in political circles as “that Jew from South Dakota.” We hit it off, and he talked to me about doing grassroots lobbying. 36-year-old me didn’t know much about what he meant. So he told me a story.

Many years before THAT, Stan noticed a young Congressional aide to South Dakota’s then-Senator James Abourezk – decorated military veteran, extremely bright. The aide was clearly going places. Stan decided to make sure that the next time AIPAC had a trip to Israel, the aide would go. He needed to understand the Middle East – with an AIPAC spin, of course. (Although at that time AIPAC was much more centrist than the right-wing outfit it is now).

The aide’s name was Tom Daschle. Even though he worked for Abourezk – who as the first Arab-American in the Senate was certainly not pro-Israel – Daschle himself was a reliable pro-Israel vote.

The point here isn’t the Israel/Palestine conflict: rather, I have always remembered this story because it struck me as the way one does politics for the long term. You cultivate people years, even decades, in advance. You build connections in towns and cities and local institutions. You never know which will bear fruit, but you are always looking to impress upon people and groups the importance of your issue.

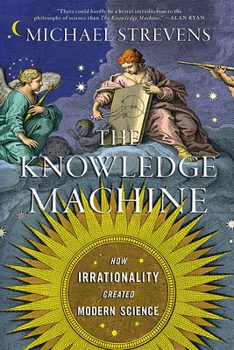

And you know who understands this sort of work better than anyone else? Scientists. We all read about great scientific breakthroughs, but if anyone gets the idea of patient work and the understanding that not all efforts will pay off, it’s scientists. Michael Strevens’ great book about the scientific revolution is titled The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science, in no small part because he argues that the entire scientific enterprise is a little crazy: taking painstaking observations over long periods of time with no assurance of usable results. That is science, but at least over the long term, it is also politics.

And you know who understands this sort of work better than anyone else? Scientists. We all read about great scientific breakthroughs, but if anyone gets the idea of patient work and the understanding that not all efforts will pay off, it’s scientists. Michael Strevens’ great book about the scientific revolution is titled The Knowledge Machine: How Irrationality Created Modern Science, in no small part because he argues that the entire scientific enterprise is a little crazy: taking painstaking observations over long periods of time with no assurance of usable results. That is science, but at least over the long term, it is also politics.

So how are you going to fund this? Well, with great difficulty. Scientists want to be in the lab doing good science: they don’t want to spend their time advocating for what they do. I get it.

But here is the beauty of the whole enterprise. Literally, science has advocates in every city and town and village in the country. They are called science teachers. If there was some way to activate science teachers even in red states, it could begin to build power. Ditto with nurses, who arethe science professional Americans interact with most frequently and are trusted. (Doctors, too, but I do not trust them to care about science).

It won’t be allowed in Oklahoma and it won’t matter in Maryland. But in purple states like Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Arizona, Nevada, and North Carolina, it could matter a lot.

In 2019, AAAS created the Local Science Engagement Network and has developed some good advocacy materials, but at least to my mind, it still seems more, well, academic. It isn’t doing community organizing among people who could actually to take a more aggressive stand locally.

I get that it’s expensive. It’s a big country, so you cannot operate everywhere. Now, I believe that the Local Science Engagement Network should focus resources on 2-3 localities and swing states and, like any good scientist, measure results. A partnership with the Environmental Voter Project, which uses big data to identify potential pro-environmental voters and seeks to mobilize them, might be interesting. Could focused advocacy efforts in some districts and areas begin to move the needle? We won’t find out unless we try.

I get that it’s expensive. It’s a big country, so you cannot operate everywhere. Now, I believe that the Local Science Engagement Network should focus resources on 2-3 localities and swing states and, like any good scientist, measure results. A partnership with the Environmental Voter Project, which uses big data to identify potential pro-environmental voters and seeks to mobilize them, might be interesting. Could focused advocacy efforts in some districts and areas begin to move the needle? We won’t find out unless we try.

This is going to be a long slog. Disinformation is rampant; Twitter has become a den of anti-vaxxism, climate denial, and neo-Nazism. But scientists are good at long-term planning; they know what a research program is. It will be, in John Kennedy’s famous words, a long twilight struggle. But that makes it all the more necessary.

Reader Comments