China and the Paris Agreement

The Long Road from Copenhagen to Paris

Six years ago in Copenhagen, China was seen as the spoiler. A widely read article claimed that China had “wrecked” the Copenhagen deal. One of China’s lead negotiators suggested that American envoy Todd Stern was “ignorant,” lacking in “common sense” or “extremely irresponsible.”

Six years ago in Copenhagen, China was seen as the spoiler. A widely read article claimed that China had “wrecked” the Copenhagen deal. One of China’s lead negotiators suggested that American envoy Todd Stern was “ignorant,” lacking in “common sense” or “extremely irresponsible.”

What a difference a few years can make. On Saturday in Paris, China’s lead negotiator Xie Zhenhua was all smiles, glad-handing his way through the plenary room. Moments after the adoption of the historic Paris Agreement, he capped China’s two weeks at COP21 with a relatively statesmanlike performance before the plenary group (see here @ 44:17). The Paris Agreement, in his view, was “fair and just, comprehensive and balanced, highly ambitious, enduring and effective.”

“The agreement is not perfect,” Xie said, “however, this does not prevent us from marching forward with this historic step.”

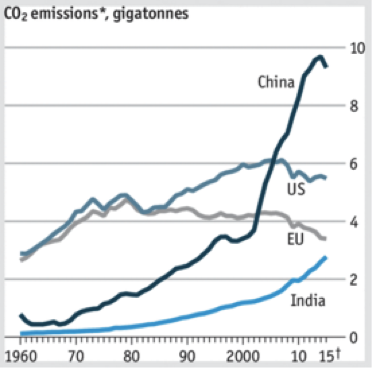

Six years ago, China was still coming to grips with its newfound status as the global leader in greenhouse emissions. Its only official side event in Copenhagen was an elaborate scholarly exposition on why by historical emissions standards China still had carbon space, whereas the US and EU had already entered carbon “bankruptcy.”

In Paris, China was now the dominant leader in greenhouse gas emissions, representing nearly 30% of global emissions (compared to about 16% for the US, 11% for the EU, and 6% for India).

But China had also undertaken a surprisingly expansive slate of climate change policies and programs to which leaders could point. Policies included:

- A target to peak carbon emissions by 2030 (or sooner),

- A target to obtain 20 percent of China’s primary energy from non-fossil energy by 2030,

- A range of carbon, energy and pollution targets in China’s 12th five-year plan,

- The introduction of a national carbon cap-and-trade program in 2017, and

- Programs to promote lower-carbon strategic emerging industries.

China’s coal use fell for the first time in 2014. And it is hard not to be impressed by China’s advances in non-fossil energy investment. The Economist, for example, noted that last year:

[M]ore than half of [China’s] new energy needs were met using low-carbon sources, including wind, sunlight and nuclear power. Indeed, China invests more in renewable-energy production than America and Japan combined.

These actions and developments reflect, among other things, a fundamental (and hopefully durable) change in political will within China on climate change and the environment. As I have written about elsewhere (see here and here), greater official concern about the environment has primarily been driven by domestic concerns about “economic transformation” (shifting away from heavy industry to higher-value added industries and domestic consumption) and the social and economic costs of emergency-levels of pollution.

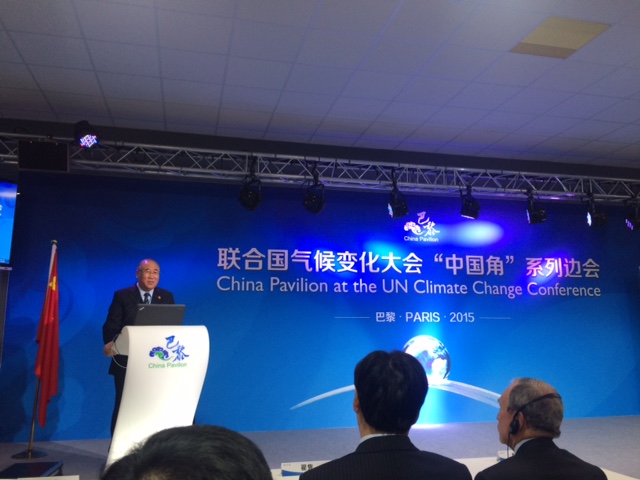

At the same time, it was clearly important to Chinese leaders to be seen as a “responsible major developing country” (负责任的发展中大国) at the Paris talks. Chinese leaders worked closely with the US to orchestrate two major US-China announcements in the year leading up to Paris (2015, 2014) that helped to set a constructive tone for the talks and head off the skeptics (particularly in the US) who took the view that China will never do anything on the environment. The China Pavilion at the Le Bourget negotiation site in Paris ran up to four events a day, with extensive participation from international experts (including several leaders from California state government), to highlight the progress China had made on low-carbon development, climate change mitigation, adaptation, finance, and a host of other topics.

With the success of Paris now behind us (see here, here, and here for very good commentary on the meaning of the overall agreement), our focus now shifts back to the domestic context. For China, I hope that the Paris Agreement will be a forceful domestic validation of those within China who have long pushed for climate change mitigation, environmental protection, international engagement, and the idea that environmental priorities are not incompatible with national prosperity.

Now the hard work begins. As Xie Zhenhua said in Paris on Saturday: “The Paris Agreement is a historic landmark. The next step is implementation.”

(Source for chart; photo credits, both Alex Wang)

Reader Comments

One Reply to “China and the Paris Agreement”

Comments are closed.

Alex said;

“….Now the hard work begins….. The next step is implementation.,,,”

Dear Alex,

I doubt that anyone is actually working very hard on implementing nebulous “goals” that are not legally binding. Who cares? The Paris conference was a lot of fun for those fortunate enough to attend, the next step is finding funding for the COP22 conference in Morocco.