California groundwater management, science-policy interfaces, and the legacies of artificial legal distinctions

By Dave Owen and Michael Kiparsky

One of the many noteworthy features of California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) is that it requires local government agencies to consider and address the effects of groundwater management upon interconnected surface water. That requirement is an important step towards rationalizing California water management, which has long treated groundwater and surface water as separate resources. The requirement also is part of a larger story about evolving science and policy in a changing world.

Science, policy, and the groundwater-surface water divide

From a scientific perspective, the surface water provision of SGMA is unremarkable. Scientists have long understood that groundwater and surface water are integrally connected. Many aquifers receive recharge from surface wetlands and streams, and many surface waterways receive much of their flow from groundwater. To a hydrogeologist, treating groundwater and surface water as separate resources makes no sense.

Policy, however, has often ignored science, and laws have often mandated separate treatment of groundwater and surface water. In many states, even as legal systems for surface water became increasingly detailed and sophisticated, groundwater law occupied a separate sphere or was largely undeveloped (interestingly, in a somewhat different legal context, the US Supreme Court will soon grapple with groundwater-surface water interactions and artificial separations). Though some states have moved towards unified systems, California was a particularly notable laggard on this issue. Prior to SGMA, no state law expressly required integrated groundwater-surface water management.

SGMA’s efforts to link groundwater and surface water therefore are important because they remove a legal barrier to allowing water management to reflect physical reality, and also because they take a big step toward rectifying lawmakers’ years of disregarding scientific understanding. But these efforts also raise bigger questions: what happens after legislation corrects a legal fiction, yet divisions of authority, management practices, and habits that were predicated upon that fiction remain? What else needs to happen to move from legal misunderstanding to effective resource management?

Science-policy interfaces

Through legal research combined with analysis of data and insights from participatory workshops, we developed some answers to these questions. The results were recently published in Environmental Research Letters, in an article that builds on a report we released in 2018.

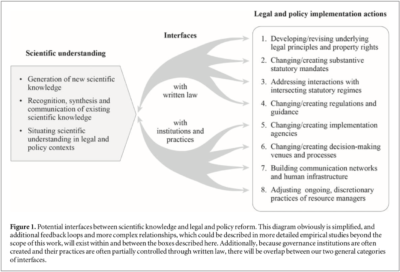

The article explains where key challenges remain for California’s efforts to integrate groundwater and surface water management. More generally, it provides a framework for understanding other efforts to bring legally-driven resource management into line with scientific understanding. This framework reveals a key assumption in the literature addressing science-policy interactions. Much of that literature describes policy-making in broad and undifferentiated terms, often referring simply to “the science- policy interface.” But as SGMA illustrates, the complex and multi-layered nature of policy-making means that a successful reform effort may need to address many science-policy interfaces (see Figure).

Addressing that complexity creates challenges, but it also creates opportunities for better interactions between scientists and policymakers.

From a practical perspective, our work emphasizes a second point that is front and center for those working on groundwater in California today, but which may be hidden in plain sight from the general public: the reconciliation of law and science is a process that does not end with the passage of legislation, or with any other single intervention. For California groundwater, the historical statutory division of this interconnected resource has left legacy effects that still linger, and that may continue to linger long after legislators have moved to other priorities.

Ultimately, our work illustrates the complexities of reconciling law with science, and highlights the need for continued vigilance and an ongoing focus on implementation of SGMA. The legislative sprint is behind us, but the implementation marathon will continue.

This blog post draws on the journal article and report produced by an interdisciplinary UC Water team of co-authors including ourselves, Alida Cantor, Thomas Harter, and Nell Green Nylen.

Reader Comments

3 Replies to “California groundwater management, science-policy interfaces, and the legacies of artificial legal distinctions”

Comments are closed.

Ironically, including surface water within the scope of groundwater management may lead to surface water mismanagement.

The State Water Resources Control Board (State Water Board) administers surface water rights and generally requires permits and licences for diversion and use of surface water, as well as subterranean streams. Consequently, groundwater wells that are connected to subterranean streams have been regulated by the State Water Board.

By contrast, groundwater wells that are not connected to subterranean streams are not regulated by the State Water Board.This lack of regulation at the State level has led to overdraft and subsidence of groundwater basins, among other consequences, which the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) was intended to mitigate.

However, the SGMA continues to allow local authorities to manage groundwater through Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs), which are required to develop groundwater sustainability plans that include interconnected surface water. This means that surface water that is connected to groundwater (without a subterranean stream) may be managed by the same local authorities that have been responsible for mismanaging groundwater.

Oh well.

Direct link to article here: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/ab0751

You are correct that there is a disconnect for groundwater between the necessity for a legal description as a property right and its physical location and quality in space and time in a depleting resource as in the San Joaquin Valley. Relative to the latter USDA – ARS in cooperation with the California state Department of Resources starting in 1959 carried on field research on groundwater recharge which culminated in the Leaky Acres project in Fresno. This work indicated that to balance the overdraft with artificial recharge and establish sustainable production from depleting basins is not a simple engineering problem. For once our research project was discontinued in 1978, management was taken over by the City and the source of surface water was altered by land-use changes and as a result the inflow quality no longer met our recommended water turbidity standards. The project eventually sealed from sediment deposition.

Other issues associated with successful artificial recharge is described in the literature we produced at the project. You indicated that it is absolutely necessary to acquire data on the current sites proposed for a recharge. This data is site specific and requires getting hands dirty in the process. As such it is not a simple “engineering” problem or project. Nor is academic rhetoric going to lead to answers associated with the physical complexity toward a sustainable balance in the water resources in any groundwater basin.