Can Planting Trees Solve Climate Change?

Unfortunately, a new scientific paper overstates forests’ potential

Today, The Guardian reports:

Tree planting ‘has mind-blowing potential’ to tackle climate crisis

Planting billions of trees across the world is by far the biggest and cheapest way to tackle the climate crisis, according to scientists…

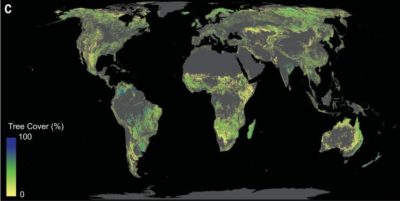

As trees grow, they absorb and store the carbon dioxide emissions that are driving global heating. New research estimates that a worldwide planting programme could remove two-thirds of all the emissions that have been pumped into the atmosphere by human activities, a figure the scientists describe as “mind-blowing”.

And the underlying scientific paper, published in Science, makes an unambiguous claim:

ecosystem restoration [is] the most effective solution at our disposal to mitigate climate change.

[See also the press release from ETH Zurich.]

That is, the authors claim that reforestation is more effective than reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Unfortunately, this is misleading, if not false, as well as potentially dangerous. It is misleading for several reasons.

- The authors do not define “effective.” Many policies and actions that could achieve a single given objective are impossible or undesirable.

- They do not consider cost. Planting trees requires arable land, physical and natural resources, and labor, all of which could be used for other valuable purposes. The most recent assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) gave a range of $20 to $100 per ton of removed carbon dioxide (CO2), [PDF, p. 851]; which is roughly the same costs as many means of reducing greenhouse gas emissions that are presently under discussion.

- The authors do not consider how such reforestation might come about. This land — roughly the size of the US, including Alaska — is owned and managed by many private persons, companies, nongovernmental organizations, and governments. How these numerous diverse actors could be incentivized or somehow forced to undertake expensive reforestation efforts is important unclear.

- They do not consider the rate of carbon removal. The IPCC gives a high-end estimate of 14 billion tons CO2 per year [PDF, p. 851], whereas humans’ emissions are about 40 billion tons per year. Thus, at this generous rate, reforestation could only compensate for a third of current emissions, with not impact on accumulated atmospheric carbon dioxide. Furthermore, the amount of removal suggested by the new paper would require about 55 years.

- The authors simply assume that all potentially forested land “outside cropland and urban

regions” would be “restored to the status of existing forests.” People use land for purposes other than crops and cities. For example, humans’ largest use of land — agricultural or otherwise — is rangeland for livestock. Thus, the paper implicitly assumes a dramatic reduction in meat consumption or intensification of meat production. - They reach a remarkably high estimate of carbon removal per area. This paper indirectly says that 835 tons CO2 could be removed per hectare (that is, 10,000 square meters), whereas the IPCC report on Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry reaches values from 1.5 to 30 tons per hectare. In a critique, Profs. Mark Maslin and Simon Lewis say “The authors have forgotten the carbon that’s already stored in the vegetation and soil of degraded land that their new forests would replace. The amount of carbon that reforestation could lock up is the difference between the two.”

- The paper does not address the (im)permanence of trees, which could later be cut down. A recent investigation by a reporter at Propublica concluded:

In case after case, I found that carbon credits [for reforestation] hadn’t offset the amount of pollution they were supposed to, or they had brought gains that were quickly reversed or that couldn’t be accurately measured to begin with. Ultimately, the polluters got a guilt-free pass to keep emitting CO₂, but the forest preservation that was supposed to balance the ledger either never came or didn’t last.

Ultimately, if cost, feasibility, and speed were no matter, then one simply could claim that permanently ending the use of fossil fuels tomorrow is the most effective. This statement would be true, but largely irrelevant.

Actually, the lead author does comment on cost to The Guardian (not in the original scientific paper). Prof. Tom Crowther says:

The most effective projects are doing restoration for 30 US cents a tree. That means we could restore the 1 trillion trees for $300 billion, though obviously that means immense efficiency and effectiveness. But it is by far the cheapest solution that has ever been proposed.

He here makes the major error of assuming that the lowest possible current cost would apply to the entire large scale endeavor. Yet as one buys more of some good or service, prices generally increase. This is because production would increasingly rely on less efficient means as well as resources that could be put to other, competing uses. As an economist would say, supply curves slope upward. Taking the midpoint of the IPCC’s cost range (that is, $60 per ton CO2, which is arguably generous), the cost would actually be about 24 times greater than Crowther’s estimate.

How is this paper dangerous? It will likely to be used to argue that we can rely more on reforestation to reduce climate change, potentially displacing efforts toward other responses: emissions cuts, adaptation, other carbon removal methods, and solar geoengineering research. (Update 1:12 PM California time: As if on cue, an editorial in The Guardian uses the scientific paper as well as the lead author’s claims of cost to assert “Without the sequestration of carbon the world will bust through 1.5C of warming and head for much worse. Planting trees is by far the least expensive and most practicable way available at present to do this.”)

Reforestation and “other natural climate solutions” should be part of the diverse toolbox to reduce climate change and manage its risks. But statements and media coverage like this feed the false belief that we could stop climate change– through “natural” to boot — if there were only sufficient public awareness and political will. However, this is not true.

Update (October 21, 2019): Science has published four comments (1, 2, 3, 4) on the paper, as well as a response from the original authors. The former group variously describe the paper as “inconsistent with the dynamics of the global carbon cycle and its response to anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions” and “neglect[ing] considerable research into forest-based climate change mitigation during the 1980s and 1990s,” and its conclusions as “incorrect” and “approximately 5x too large.”

The original authors respond that “We did not suggest that tree restoration should be considered as the unique solution to climate change. To avoid this confusion, we have corrected the abstract accordingly.” But they did say exact that. As cited above, Crowther told the news media that reforestation “is by far the cheapest solution that has ever been proposed.” The associated press release was originally titled “How trees could save the climate” and in it, Crowther said “Our study shows clearly that forest restoration is the best climate change solution available today.” They have since changed the press release, with a footnote.

Reader Comments

8 Replies to “Can Planting Trees Solve Climate Change?”

Comments are closed.

Too much hyperbole on both sides of this equation, in my view. Title of the blog begs the question. No credible proponents of increased biological carbon sequestration are asserting that planting trees can “solve” climate change. Clearly, though, enhancing bio sequestration in a responsible, sustainable way, could be an important tool to help mitigate emissions, particularly over the near term — when we arguably need it most— as we (hopefully) transition to a decarbonized energy sector.

Under the university press release headlined “How trees could save the climate,” the lead author is quoted saying “Our study shows clearly that forest restoration is the best climate change solution available today.”

https://ethz.ch/en/news-and-events/eth-news/news/2019/07/how-trees-could-save-the-climate.html

That seems rather close to asserting that planting trees can “solve” climate change.

Various ocean methods may also be a part of the negative emissions required by the recent IPPC report, but we need several Gtonnes per year, so there is no single solution.

If trees store CO2, we will run out of oxygen soon. I was thought trees store carbon and release oxygen during day. How things change quickly.

Thanks to Jesse Reynolds for a much needed corrective.

You are welcome!

as always

americans

distorting the truth in order to keep their business growing

if the profits oil corporations make , go to reforestation, problem solved

see my very very simple post

global heating

see in you tube

juane cutter global heating an easy solution

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=otyewJTHMN0

don´t trust these fake corporations

There may be a more rapid and cost-effective, biologically-based CO 2 capture mechanism, than planting new forests, which also allows for the immediate reuse and sequestration of the captured carbon in cost-advantaged bio-products.

Using our our recently-patented Combined Remediation Biomass and Bio-Product Production (CRBBP) Process, we plant and then multi-task fast-growing bio-crops and their resulting biomass to do good things for people and the planet, less expensively.

According to an analysis done for us, by a University of California-Berkeley researcher, over a 15-year span, equivalent acreages of our preferred bio-crop (Biomass Sorghum) will extract 3 times the CO 2 of newly-planted pine trees and 2 times the CO 2 extracted by other crops, including bio-crops, like switchgrass.

As one who agrees in reforestation as a long-term goal, as we approach the edge of the pending climate catastrophe abyss, I hope that policymakers will understand the need for using the most rapid and cost-effective CO 2 capture techniques available.

Sincerely,

Joe James,

President, Agri-Tech Producers, LLC – 803-413-6801