And the Survey Says…

How to interpret and utilize “environmentalist” poll results showing widespread support for environmental protection

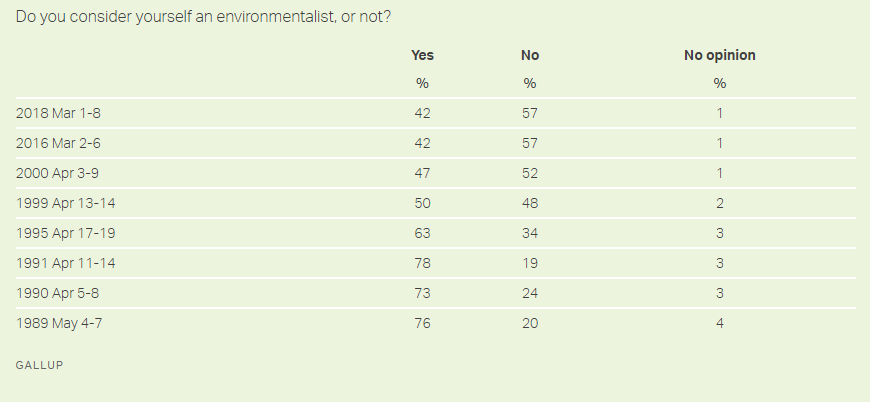

As most of us know by now, environmentalism in the United States has increasingly become a politically polarizing topic. A Gallup poll from March 2018 revealed that only 42% of surveyed individuals consider themselves to be “environmentalists,” a figure which has decreased over time from the early 1990s:

Interestingly, however, this shift in identity for “environmentalists” does not appear to coincide with any meaningful changes in beliefs about environmental policies. The same March 2018 respondents reported a 73% response rate in favor of stronger enforcement of federal environmental regulations. The results of a more recent Gallup poll from March 2019, available at the same link posted above, reveal that 47% of respondents worry a “great deal” about the quality of the environment, with only 18% of respondents reporting “only a little” worry and a mere 8% answering “not at all.” Other noteworthy results of the March 2019 survey include:

- 61% of respondents stating that the U.S. government is doing too little to protect the environment;

- 64% of respondents believing that the quality of the environment is getting worse; and

- 65% of respondents agreeing that protection of the environment should be prioritized, even at the risk of curbing economic growth.

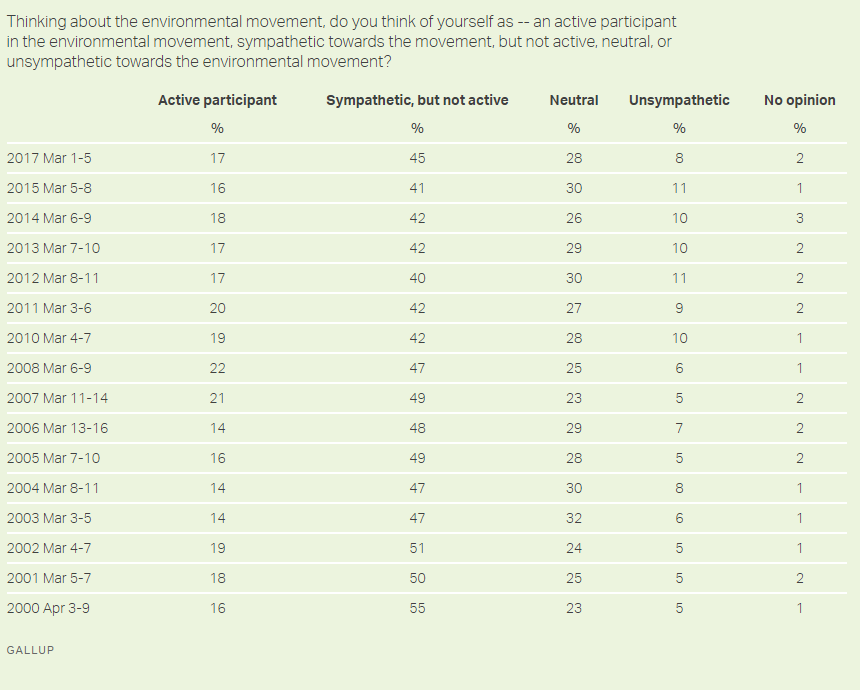

Importantly, 45% of respondents to a Gallup poll from March 2017 identified themselves as sympathetic with the general environmentalist movement but not active in supporting the movement, a number which has slightly trended downward over the past 20 years:

There are some noteworthy deficiencies with these polling figures and their utility for understanding and interpreting support for environmental initiatives. It is not entirely clear what respondents subjectively believe the phrase “quality of the environment” means, or how respondents assessed whether environmental quality is changing in either direction. Equally vague is each respondent’s definition of “too little” governmental action or to what extreme respondents would be willing to elevate environmental protection over economic considerations. And of course, the definition of “environmentalist” is not static; it may be that modern conservatives are less likely to consider themselves “environmentalists” out of fear of being perceived as supporting policies inconsistent with the Republican party, and even some moderate Democrats might not identify as environmentalists when comparing themselves to their more activist-oriented liberal peers. Nor is there an indication as to what percentage of the 45% of sympathetic but inactive respondents also identifies as an “environmentalist,” which adds another level of uncertainty about the subjective connotations of the term. Finally, there are likely historical class- and race-based associations with the word “environmentalist” that could cause certain respondents falling within a particular demographic or socioeconomic category not to identify themselves as environmentalists. Nevertheless, it is still evident from the above figures is that there continues to be strong motivation in favor of environmental protection among the broad United States population, even among those who do not view themselves as “environmentalists.”

Improving environmental activism through enhanced connection to the natural environment

These poll results, which demonstrate strong majority support for policies that protect the environment, collectively raise the question: how can we encourage those who desire stronger environmental protections to be more active in effectuating policies consistent with that goal? Logically, converting the number of inactive supporters into active environmentalists would better channel the collective political motivation for environmental protection into actual laws and policies designed to do so more effectively. Indeed, elected officials and other policymakers consistently take steps that are wholly inconsistent with these widely-supported environmental goals; to pick an obvious example, the Trump Administration has continued to promote fossil fuel development, even though 71% of respondents to a March 2017 Gallup poll stated that the United States should emphasize alternative energy sources instead.

Putting political polarization aside, in my view, one potential under-discussed factor driving the lack of action among the sympathetic portion of the population is the absence of a strong emotional connection to “the environment.” Intuitively, those who spend less time in nature are more distanced from the environmental issues they support and are less capable of visualizing the impacts of climate change, pollution, or other mechanisms of degrading or eliminating open space. Therefore, finding ways to encourage people to explore the outdoors more frequently—whether in their own communities or elsewhere—might drive more of these inactive sympathizers to action in support of environmental policies.

It is also highly probable that individuals who feel such a connection to the environment are more likely to educate themselves about threats to the continuing prosperity of the environment. As the number of people who are concerned about climate change continues to increase, especially among youth, it becomes even more crucial to provide this portion of the population with the complete facts about the potential global harm that likely would arise if we stay the course on greenhouse gas emissions. Surely, the lack of sufficient knowledge about climate change and the like opens the door for misinformation campaigns commonly utilized in today’s political climate as justification for resisting certain environmental protection measures. The March 2019 Gallup poll shows that, in response to the question of how well do you feel you understand global warming, 18% of respondents answered “not very well,” and 2% reported having no understanding of the issue at all. Given the extensive scientific literature and accepted consensus about the manmade causes and anticipated effects of climate change, the 20% of the population that identify themselves as under-educated in that space can be seen as an untapped reservoir of environmental activism that could greatly influence future climate change policies.

This notion is true not only for policies that protect the natural environment, but also for policies pertaining to human health and environmental justice issues. It is common knowledge that disadvantaged or minority communities often bear a disproportionate share of the health impacts from pollution, industrial activity, and climate change (a recent example of a study by scientists with the Environmental Protection Agency can be found here). One mechanism to reverse this trend is through community empowerment: when individuals are fully knowledgeable about the impacts to their communities and are motivated to reverse the trend, activism campaigns may generate more local support and are likely to be more effective. Therefore, linking disadvantaged communities to their local “environment” could produce community members who are more fully informed about the risks they face and could drive beneficial environmental improvements at the local level, which might not otherwise be considered in broader regional or national advancements in environmental policy.

For these reasons, policymakers aiming to garner more support for environmental initiatives should consider implementing policies that encourage greater community engagement with the natural environment, at the same time as attempting to address substantive environmental issues directly. This is not as much a short-term solution as it is a forward-looking strategy to generate political inertia down the road for necessary and more substantial environmental policy changes. The present political climate is apparently not suitable for drastic measures—for instance, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and cutting carbon emissions dramatically over the coming years, as will be necessary to mitigate against the most severe impacts of climate change (refer to the 2018 report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change for the substantial emissions reductions necessary to keep global warming at or below 1.5° Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels)—but perhaps in several decades those measures would be feasible if everybody who cares about reducing climate change impacts is a fully-actualized supporter of those policies. While the primary focus on improved access to nature is typically the health and equity benefits afforded to disadvantaged communities (see this recent study linking access to nature during childhood with improved mental health in adulthood as one example), increased political support for environmental issues may be a positive byproduct of improving how we interact with the natural environment and should not be discounted as a beneficial tool for future policy changes at the local or national scale.

In future posts I plan to analyze different mechanisms to enhance community engagement with nature, in order to achieve this objective of increased political pressure for environmental protection, so stay tuned!

Reader Comments