The $133 Million Bat Tunnel

Here’s what permitting reform in the United Kingdom can teach the United States about building and abundance.

“We’ll rip out ‘insane’ environmental rules that block growth.”

“We can’t get anything built anymore. Everything takes too long.”

“We will streamline environmental obligations. We will limit the cynical legal challenges that block major infrastructure projects. We will strip away the years of consultation that drown builders.”

You might well expect these threats and worries were voiced by American politicians and pundits. And you’d be mostly but not entirely right. “Why America can’t build anymore” has been a red hot topic in recent years (for a quick sample check out here and here and here). Whether it’s affordable housing, the low-carbon energy transition, or transportation, a growing movement known as “abundance liberalism,” argues Americans have lost their way when it comes to infrastructure. This lies at the heart of Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s new book, Abundance, now sitting atop bestseller lists. There are many reasons why it takes longer and is more expensive to build in the US than in other countries, but one major concern is permitting.

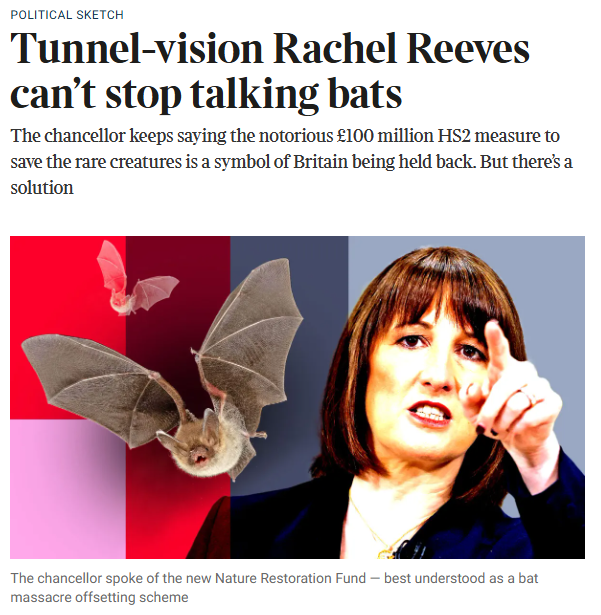

While the quotes above could have come from US voices, they actually came from “across the puddle.” They were made, respectively, by the UK Treasury Minister (Rachel Reeves), Deputy Prime Minister (Angela Rayner), and Prime Minister (Keir Starmer). Indeed, the Labour government has been engaged in a very similar permitting reform debate to the one raging in the United States, but it is more advanced at the government level. Americans can learn from their experience.

Abundance liberals argue that Americans have overregulated infrastructure development. Despite good intentions, we have “fetishized procedure” to the point where the costs can outweigh the benefits. Focusing on environmental laws, we are seeing that many of the environmental laws we adopted over 50 years ago to battle “brown” infrastructure so effectively are proving equally adept at obstructing “green” infrastructure.” JB Ruhl and I examined this dynamic in The Greens’ Dilemma and it has become a concern shared on both sides of the political aisle. The Inflation Reduction Act showed that we can fund renewables infrastructure but it’s an open question how fast we can build it. Even climate champion Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, has argued that “We need to make it easier to build electricity transmission lines.”

The Trump administration has already taken on permitting reform. Its most focused strategy to date has been to declare an “energy emergency” in an executive order and then use that as the basis to short circuit environmental review procedures. Just two weeks ago, the Department of Interior stated that it was reducing permitting procedures for energy projects (pretty much anything except renewables) from years to just 28 days. Careful analyses of the legal basis for these claims have been prepared by the Berkeley Center for Law Energy Environment (here) and Columbia’s Sabin Center for Climate Change Law (here). This strategy is unlikely to survive judicial challenge.

Permitting reform remains a fast-moving topic and I expect we will see proposed bills from Congress in the next few years, and likely even bipartisan proposals when the emergency approach fails in the courts. But what about the UK, where legislation has already been drafted?

The poster child for permitting reform in the UK has been the so-called “Bat Tunnel.” A high-speed rail line, known as the HS2, has been under construction to connect London with the West Midlands and Manchester. The line was planned to run through a wooded area in Buckinghamshire. A wildlife survey during the permitting process revealed that there were protected bat species and other rare invertebrates and birds. The developers proposed, and Parliament then funded, the 900-meter “Sheephouse Wood Bat Protection Structure” at a cost of £100 million, equivalent to $133 million. Calling it a “protection structure” or “tunnel” is bit misleading, since it looks more like a futuristic ribbed covering from a 1970s sci-fi movie set. Imagine Logan’s Run on wheels.

The Labour government made big promises during the election campaign to build 1.5 million new homes during its five-year term to address housing affordability. There are many reasons why this may be infeasible, but the government has seized on permitting as a major obstacle and offered the Bat Tunnel as the prime example for why things need to change. It’s not exactly America’s small perch fish (the snail darter) that famously blocked the completion of a dam in the fundamental Endangered Species Act case, TVA v. Hill, but the optics come pretty close. A local bat population versus a high-speed rail line doesn’t sell well.

Featuring the Bat Tunnel as emblematic of what is wrong with environmental protection, Prime Minister Keir Starmer has announced that it is necessary to override “the whims of NIMBYs who have been holding us back for too long” and put an end to “using our court processes to frustrate growth.” The government has recently proposed major changes to the permitting and review process in its proposed Planning and Infrastructure Bill.

Among other changes, the Bill reduces the availability of legal challenges (from the current three to two for most projects and only one if it is deemed “totally without merit”). Local planning committees’ powers would be limited, too, making it more difficult for elected officials to oppose specific projects. And majority support would become sufficient for permitting, removing the veto power of an individual planning authority.

Perhaps most important, rather than require developers to follow the hierarchy of avoidance and then mitigation if the harm can’t be avoided, developers could now turn directly to in-lieu fees, paying into a “Nature Restoration Fund” if there will be wildlife impact at a site.

Environmentalists in the UK have pushed back hard, arguing that such fundamental changes are an overreaction to a system that works. A preliminary environmental review would quickly have revealed the rare wildlife in Sheephouse Wood and this whole Bat Tunnel spectacle could have been avoided if the route had been planned around that forest instead of barreling straight through it. An op-ed in The Guardian called the bill “the worst assault on England’s ecosystems in living memory.” Critics have pointed out that the proposed bill hardly lives up to Labour’s election promise “to restore and protect our natural world…[T]o unlock the building of homes… without weakening environmental protections” And, of course, while there may well be a place for in-lieu fees, some aspects of nature (like old growth) simply cannot be restored with money for good works somewhere else.

Environmentalists in the UK have pushed back hard, arguing that such fundamental changes are an overreaction to a system that works. A preliminary environmental review would quickly have revealed the rare wildlife in Sheephouse Wood and this whole Bat Tunnel spectacle could have been avoided if the route had been planned around that forest instead of barreling straight through it. An op-ed in The Guardian called the bill “the worst assault on England’s ecosystems in living memory.” Critics have pointed out that the proposed bill hardly lives up to Labour’s election promise “to restore and protect our natural world…[T]o unlock the building of homes… without weakening environmental protections” And, of course, while there may well be a place for in-lieu fees, some aspects of nature (like old growth) simply cannot be restored with money for good works somewhere else.

The bill has not yet come up for a vote, but Labour controls a majority so some legislation seems likely though it may take a different form.

So, what can we take from the British experience for the permitting reform debate in the US? Here are three things to consider.

First, stories matter, and so do pictures. Ridiculing legal protections for bats and great crested newts is easy and hides the more compelling protections that conservation laws assure. Just as we have seen US universities responding to threatened cuts to grants by highlighting the life-saving research at stake, the permitting reform debate needs to highlight more stories and images of what physical nature has been conserved rather than the sacrosanct nature of laws such as NEPA and the ESA.

Second, the popular pressure to build more housing, improve transportation infrastructure, and decarbonize the grid is very real on both sides of the Atlantic (both at the local as well as national levels, as Jonathan Zasloff’s recent post on CEQA makes clear). Voters are likely most focused on housing, but the permitting challenges are similar. Politicians respond to the public, so a strategy of pure defense in maintenance of the status quo is likely to prove inadequate.

Third, the environmental community needs to play a central role in developing and debating what the next generation of environmental protections should look like. This may seem like the wrong time to be focused on the issue, given the administration’s environmental initiatives in its first 100 days (set out in Dan Farber’s recent Legal Planet post). In the current political landscape, where challenges to environmental protections are coming fast and furious, plans for permitting reform legislation may seem a second order concern.

But my hunch is that the current “emergency” declaration strategy toward permitting will not survive court challenge and that meaningful reform will have to come through Congress, where there actually appears to be growing interest. When that happens, there will need to be the kind of back-and-forth debate now taking place in the UK.

Greatly weakening environmental protections in the name of permitting reform is unwarranted. The US has had strong environmental protections in place while growing the economy over more than five decades. That is an enviable record. But change is coming. There is a growing concern in Congress that it has become too difficult to build in the US. This clearly has been the case with renewables infrastructure, and this was evident well before the 2024 election (this is our 2020 piece on the topic). For the most recent example, look no further than the recently unveiled Republican budget proposal that would, among other things, streamline permitting for renewable energy projects on public lands.

This is all to say that we should pay careful attention to the path of the proposed UK infrastructure bill. Their legislative process is likely one or two years ahead of us, and we can learn a great deal by understanding which compromises stick, which arguments sway voters. With any luck, there’s light at the end of the Bat Tunnel.

Reader Comments