Trump Administration’s Cold Water War With California Turns Hot

Feds’ Curious New Lawsuits Against State Water Board Likely Just the Opening Litigation Salvo

When it comes to California water policy, the federal-state relationship has always been both strained and challenging. That intergovernmental tension harkens back at least to the Reclamation Act of 1902. In section 8 of this iconic federal statute that transformed the American West, Congress declared that the federal government “shall proceed in conformity with” state water rights law. And, in its 1978 California v. United States decision, the U.S. Supreme Court expressly held that the federally-constructed and operated Central Valley Project (CVP) in California is subject to the water rights jurisdiction of (including permit conditions imposed by) California’s State Water Resources Control Board. Finally, in the 1992 Central Valley Project Improvement Act, Congress underscored the California v. United States precedent regarding state water rights primacy over federal CVP water rights when it legislated environmentally-friendly reforms to the CVP’s operations.

At the operational level, federal and state water managers have coordinated operations of the CVP and the parallel State Water Project for many decades. That’s been consistently true over the years, despite shifting Republican and Democratic presidential and gubernatorial administrations. Such federal-state water project coordination is generally a good thing, ensuring efficiencies and avoiding conflicts in the day-to-day operation of these two mammoth water delivery systems, upon which most Californian residents and the state’s robust agricultural sector depend.

But this intergovernmental water policy Era of Good Feeling (relatively speaking) has come to a sudden and dramatic end with the ascension of the Trump Administration.

The trouble began in 2016. when presidential candidate Donald Trump told a campaign rally in California’s Central Valley that there’s plenty of available California water, if only California water managers would halt their “insane” practice of letting water be “wasted” by allowing some of it to flow, unconsumed, out to sea. (This ignores the fact that if all of California’s water runoff was diverted for human uses before reaching the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, diversions from the Delta upon which 23 million Californians and state agriculture depend would become too saline for human consumption or agricultural irrigation purposes. But that’s another story…)

One defining characteristic of President Trump: he tries very hard to make good on his campaign pledges. It’s his administration’s efforts to do so that are putting the federal government and the State of California on a war footing when it comes to water policy.

Several parallel and related Trump administration water initiatives over the past year have ratcheted up the California-U.S. water wars. The first volley was fired by U.S. Bureau of Reclamation Director Brenda Burman against the State Water Resources Control Board. In a July 27, 2018 letter, Commissioner Burman strongly criticized on both legal and policy grounds the Board’s proposed Bay-Delta Plan Update, designed to increase flows in the Lower San Joaquin River and Southern Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. Her letter declared that if the Board did not substantial revise its proposal, “the Secretary [of the Interior] will request the Attorney General of the United States bring a [lawsuit] against the Board.”

Second, on August 17, 2018, then-Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke wrote a “California Water Infrastructure” memo to his senior staff declaring that the CVP is in “a desperate state of disrepair”; blaming the State of California for the problem as a result of ill-conceived conditions on CVP operations imposed by the State Water Board under its California v. United States/Reclamation Act authority; and directing his Department subordinates to, among other things, take immediate action to maximize CVP water deliveries to California farmers and ranchers; and to build new water storage facilities in California.

Third, President Trump on October 19, 2018 issued a “Presidential Memorandum” to members of his Cabinet entitled, “Promoting the Reliable Supply and Delivery of Water in the West.” President Trump announced the Memorandum in the heat of the 2018 midterm elections, during a campaign stop designed, in principal part, to support incumbent Republican members of Congress in California and other Southwestern states locked in close reelection races. (If the Memorandum was intended to bolster his party’s congressional incumbents from California’s Central Valley, the strategy failed miserably: all of those Central Valley Republican incumbents were turned out of office by the voters.)

The Trump Memorandum declares that “[d]ecades of uncoordinated, piecemeal regulatory actions have diminished the ability of our Federal infrastructure…to deliver water and power in an efficient, cost-effective way.” It directs his Cabinet secretaries to take multiple, immediate steps to “streamlin[e] Western water infrastructure regulatory processes and remov[e] unnecessary burdens.” Specifically, the Memorandum orders his senior officials to expedite environmental reviews of existing and proposed federal water infrastructure projects under both the federal Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act.

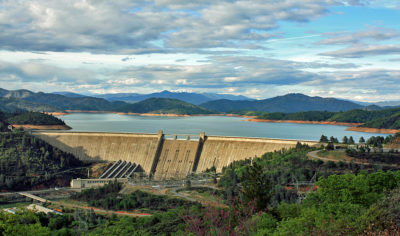

Fourth, Congress passed and on October 23, 2018, President Trump signed into law “America’s Water Infrastructure Act of 2018.” That legislation includes federal funding for two controversial Northern California water projects: the proposed raising of the level of Shasta Dam and Shasta Reservoir (the centerpiece of the CVP) by 18-20 vertical feet; and the construction of the proposed Sites Reservoir, an off-stream storage facility in the upper Sacramento Valley that would help store much of the additional water supplies captured by a raised Shasta Dam.

Fifth, finally and most recently, the Trump administration’s Justice Department on March 28, 2019, made good on its July 2018 threat to sue the State Water Resources Control Board if the Board did not back off of its plans to increase San Joaquin River and Southern Delta flows. (The Board, wisely, had refused to do so, formally adopting those plans in late 2018.)

But the legal theory upon which the Trump administration relies in mounting this legal challenge is both curious and unprecedented: it filed parallel lawsuits in federal and state courts in Sacramento, arguing that the Board violated the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) when it adopted the San Joaquin River/Southern Delta revised flow standards. Specifically, alleges USDOJ, the State Water Board’s environmental analysis of those proposed standards was deficient in not allowing more diversions from the river and Delta.

In the nearly 50 year history of CEQA, this is one of the first lawsuit under that foundational California environmental law the federal government has filed against the State of California. And, at a time when many industry and developer critics rail against perceived “abusive CEQA litigation” brought to further non-environmental objectives, the Trump administration’s newly-filed CEQA lawsuits do just that.

While USDOJ lawyers declare in their dual complaints that they’d prefer their CEQA claims be resolved in federal court, it seems far more likely that the assigned federal district judge will abstain in favor of state court resolution of those state law claims. And–to this longtime CEQA practitioner, at least–this seems a weak CEQA lawsuit at best. Put plainly, is this the best legal theory the Trump administration could come up with to challenge California state water policies with which it so fundamentally disagrees?

What’s more troubling is the larger legal and policy picture. The Trump administration has quite dramatically moved to a war footing in bringing its CEQA challenges to State Water Board actions affecting the CVP. It most certainly won’t be the last such litigation challenge.

Meanwhile, the federal government is straining mightily to expedite its efforts to launch new water projects in California that are extremely controversial and likely to generate substantial new litigation against the Trump administration. The proposal to raise Shasta Dam is particularly contentious: last year California’s Secretary for Natural Resources wrote to the Congressional leaders of both parties urging it not to authorize the project, declaring that the project, if constructed, would violate the California Endangered Species Act and other state environmental laws due to its adverse effects on California waterways and fisheries resources. Native American tribes and environmental groups also are vigorously opposed to the Shasta Dam proposal.

These Trump administration water policy initiatives are infected with the same flaws contained in numerous administration environmental and non-environmental policies: attempting to change federal law via executive order, memoranda and letters rather than through adherence to the requirements of the federal Administrative Procedure Act. That questionable approach has generated a harsh reception in the courts, which have rather consistently invalidated the Trump administration’s efforts to evade the requirements of the APA. If California chooses to challenge some or all of the federal government’s recent water initiatives in court, they seem likely to suffer a similar fate.

Some observers darkly predict that all of the above-described water policy machinations by the Trump administration have a more sinister objective: to elevate one or more of these federal-state water disputes to the U.S. Supreme Court, in order to seek reversal of the High Court’s landmark California v. United States precedent and thereby establish federal primacy when it comes to legal conflicts between federal water projects and state water law.

In any event, the Trump administration appears spoiling for a fight–on multiple legal and policy fronts–with state water regulators over water law, water policy and the operation of federal water infrastructure in California. It’s equally apparent that the State of California and its environmental allies will not shrink from what is becoming an increasingly hot federal-state water war.

Reader Comments

2 Replies to “Trump Administration’s Cold Water War With California Turns Hot”

Comments are closed.

What the frack?

Why is Trump so interested in California water? Just ask Ryan Zinke, who famously said to the oil industry, “Government should work for you.”

Although Zinke has since stepped down under cloud of scandal, he set in motion the Interior Department’s efforts to expand fracking and “enhanced oil recovery” operations in California and his successor, Acting Secretary David Bernhardt, is another oil industry shill.

California has abundant fossil fuel reserves and is currently the third largest producer of oil in the US, behind Texas and North Dakota. Kern County alone produces more oil than the entire state of Oklahoma and San Joaquin County has more fracking wells than any other county in the US.

This requires a lot of water (over 15 billion gallons in 2015) and Trump wants much more. The Interior Department is trying to expand oil production on 400,000 acres of public land and 1.2 million acres of federal mineral estates throughout California (including Fresno, San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara Counties), in addition to offshore drilling.

The Administrative Procedure Act provides some procedural protections against the Trump Administration (such as judicial standards for policy changes and public notice and comment periods), but Californians need to take action to protect freshwater and groundwater from oil production. Gerry Brown was either an enabler or a compromiser (depending on your point of view), and oil production has thrived in California during his most recent terms in office. Gavin Newsome has publicly stated his opposition to fracking and oil production in California, but his words will ring hollow without action by Californians.

Just write a new agreement with the same terms as the old one, but call it the Winning Trump Water Plan, and let him build a Trump motel in Fresno, and the law suits will go away (maybe have Ivanka sell a line of high fashion straw bracero style cowboy hats – gilded conchos on the band? – made in China as well).

Then he can claim a win and the whole matter will go away.