What Have We Learned from Recent Disasters?

Disasters are getting bigger, badder, and less predictable. We need to adjust.

Hurricanes Harvey and Maria. California wildfires. Superstorm Sandy. The great Texas blackout. The list goes on.

These mega-events dramatize the need to improve our disaster response system. The trends are striking: escalating disaster impacts, more disaster clustering, more disaster cascades, and less predictability. We need to up our game. Lisa Grow Sun and I discuss the implications in a new paper, but here are a few of the key takeaways.

Escalating impacts. From 1980 to 2020, there were an average of 7 billion-dollar events per year. (Interestingly, nearly half of them were in Texas.) But from 2015-2020, the average was 16 per year. 2020 had a record-breaking 22 billion-dollar events. Why? It’s partly higher GDP and population, so more people and wealth at risk. More people and infrastructure are located in high risk areas, especially coasts. And over and above those trends, there’s climate change — leading to a sharp increase in extreme weather events with more yet to come.

Clustering. As the number of large-scale disasters increases, the odds increase of two or three happening during a short period of time. By the time Hurricane Maria hit Puerto Rico in 2017, FEMA was already dealing with the aftermaths of two other huge storms. FEMA workers were exhausted. Equipment and supplies were already deployed elsewhere. The response in Puerto Rico suffered as a result. Similarly, in the summer of 2020, FEMA was hard pressed to deal with huge fires on the West Coast and hurricanes along the gulf at the same time.

An uncertain future. 500-year-floods are supposed to happen on average once every 500 years. We used to be able to make such judgments based on the historical record. That doesn’t seem to be true any more. In 2017, Hurricane Harvey dumped up to 60 inches of rain on some parts of Houston. It was a 500-year flood. Houston also had so-called 500-year floods in 2015 and 2016. Obviously, a 500-year flood “ain’t what it used to be.” The moral: Historical patterns of event frequency are no longer reliable — climate change is disrupting past patterns.

Disaster cascades. Hurricane Maria (Disaster 1) destroyed Puerto Rico’s power system (Disaster 2), which created a healthcare crisis (Disaster 3). The 2021 Texas winter storm (Disaster 1) caused a power blackout (Disaster 2) —partly directly, but partly because it knocked out natural gas supply systems that supplied the generators. (Disaster 3) The power blackout (Disaster 2) then caused failures at water treatment plants (Disaster 4).

There are lessons here for disaster planning. The first is the need for surge capacity. FEMA’s primary job is supplying surge capacity to states that are overwhelmed by major disasters. FEMA’s capacity, however, is itself overstretched. It’s much harder to be sure of how many separate incidents FEMA may need to handle at once. Therefore, FEMA needs access to enough extra supplies, equipment, and personnel to handle these super-surges. It also needs to have the managerial capacity to handle the additional resources that may be needed, even if all this extra capacity is only needed on occasion.

Firefighters spend time sitting around their stations for a simple reason. You don’t want to employ the number of firefighters needed to handle the average fire. You need to have enough for the big ones, and those don’t happen every day. We’ve recently learned about the need to have a public health system that’s strong enough to respond to abnormal threats, not just the everyday ones. The same is true for response to natural disasters.

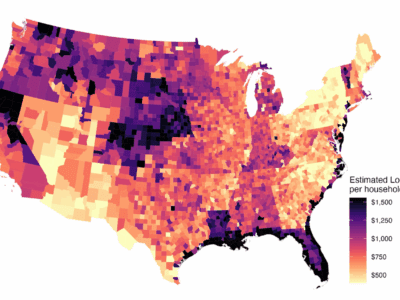

Inequality. Disasters almost always impact disadvantaged communities more than others. Those communities are often located in high-risk areas. Residents have fewer resources to prepare for, respond to, and rebuild from disasters. Climate change will only intensify the inequalities.

We face a changing, uncertain future. We can’t rely on the historical record anymore to forecast risks. Instead, we must plan for the unexpected. This requires providing resilience against a broad range of future threats, such as preserving natural buffer zones and discouraging construction in high risk areas. To avoid cascades, we also need to make systems that can be impacted by weather more resilient. For instance, add more storage capacity to the grid and more micro-grids that can function on their own. Measures like that not only reduce the direct harm from a blackout but make it less likely that a failed grid will cause other systems to fail. Finally, we need to devote more attention to disadvantaged communities, who will feel the fullest brunt of climate-related disasters.

All this will cost money. But given current trends, we only have two choices. We can spend more money on risk reduction and disaster response. Or we can just resign ourselves to merciless hammering by disasters over and over again.

Reader Comments

2 Replies to “What Have We Learned from Recent Disasters?”

Comments are closed.

Too bad UC intellectuals refuse to inform, educate and motivate the public to demand that they make the right things happen today.

Richard Hofstatder was quoted by former Berkeley Chancellor Dirk to explain this state of mind:

“—- so many intellectuals don’t want to take on the sort of complications and impurities that come with being public.”

So the latest worst case scenario consequence of this academic failure was reported today by Bloomberg:

CO₂ Reaches Its Highest Level in More Than 4 Million Years

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-06-07/co-reaches-its-highest-level-in-more-than-4-million-years?srnd=green

Apparently, academics don’t want to learn to communicate with the public, they only want to pontificate to their students like you folks on Legal Planet.

GLOBAL WARNING

Global Warming is now totally out control and the human race desperately needs an Environmental Fauci to unite intellectuals around the world to inform, educate and motivate the peoples of the world to save something for the future, because our newest and all future generations won’t have a chance at an acceptable quality of life the way things are going right now with the power of money destroying everything that makes the planet habitable for the human race and all other animals and plants.

We were warned by the “Global Warning” special issue of CALIFORNIA Magazine in 2006 and we have had absolutely no leaders to heed the warnings and make the right things happen since that issue was published.