Red States and the American Free Enterprise Chamber of Commerce are Climate Champions?

The hypocrisy in Iowa v. Wright is nauseating.

Guess which parties made the following arguments about climate change in a recently decided Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals case, Iowa v. Wright? A group of red states and the American Free Enterprise Chamber of Commerce (AMFREE).

The case involves an obscure but important formula, known as the Petroleum Efficiency Factor (PEF), applied when automakers use electric vehicles to comply with fuel economy standards (the “CAFE” standards) by assigning each vehicle what is essentially a miles per gallon equivalency. (Full disclosure: I worked on the PEF during my time with the National Highway Safety Administration as we developed new CAFE standards.) The Biden Administration’s Department of Energy issued a new PEF in 2024 that was substantially less generous for EV compliance than the old PEF but somewhat more generous than its initial proposed rule.

The plaintiffs who challenged the new PEF argued that it was too lax. They told the court that the new PEF “enables car manufacturers to continue to produce less efficient gasoline vehicles [and] DOE’s final rule results in more energy consumption [than the proposed PEF]. Increase energy consumption in turn results in increased greenhouse gas emissions.” Yes, that’s the argument made by AMFREE and the states of Iowa, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Kansas, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, and Utah. And there’s more. These champions of addressing climate change also argued that they have standing to sue the Department of Energy over the PEF because, “for those states with coastlines—Florida, Mississippi, and Texas—the increase in greenhouse gas emissions threatens to raise global sea levels and erode their sovereign territory.”

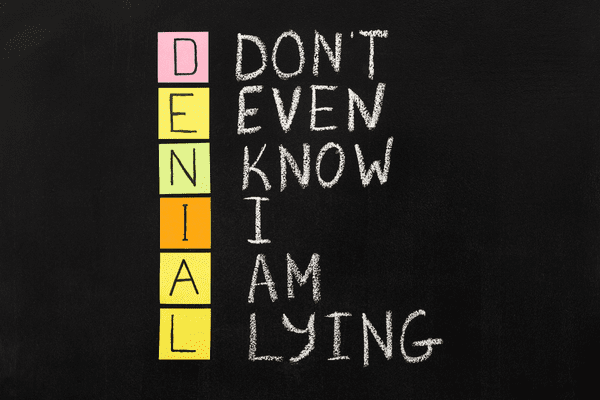

While AMFREE was arguing to the Eighth Circuit that a PEF that is weaker than originally proposed would increase greenhouse gas emissions and the risk of sea level rise, the organization was simultaneously filing comments in support of EPA’s proposed repeal of its finding under the Clean Air Act that greenhouse gases endanger public health and welfare. And while Florida, Texas and other green states were joining AMFREE’s position, their governors were busy eliminating all references to climate change in state law, rolling back support for clean energy, and denying links between climate change and damage to their states. As Florida’s governor Ron DeSantis has said, he’s “not a global warming person.”

And why, you might ask, did the plaintiffs challenge the PEF in the Eighth Circuit, with Iowa as the lead plaintiff? Because, despite the 5th Circuit’s reputation as the most rightwing appellate court in the country, the Eighth Circuit has the most judges appointed by Republican presidents — 10 of 11 — of any of the federal courts of appeals. The three judge panel that heard the challenge to the PEF did, indeed, include three judges appointed by Republicans, two by George W. Bush and one by Trump.

Lo and behold, these Eighth Circuit judges found that the plaintiffs had standing to sue based on the argument that increases in greenhouse gases from the PEF would create sea level rise that would harm the three coastal states who are parties to the litigation. The panel also held, curiously, that the new PEF would cause harm to the plaintiffs by accelerating the adoption of electric vehicles, harm that would be redressed by vacating the PEF and remanding it back to the Department of Energy. But of course accelerating the adoption of electric vehicles would reduce the very greenhouse gases that plaintiffs claim would injure them. Note to blue states and environmental NGOs: this is a great standing case for challenging Trump Administration regulations.

In addition to holding that the red states and AMFREE had standing, the panel in Iowa v. Wright then went on to strike down the new Biden Administration-issued PEF. The PEF is essentially a calculation to convert the efficiency of an electric vehicle into a fuel economy equivalent. DOE is required by statute to develop and issue a PEF based on various statutory factors and “review those values each year and determine and propose necessary revisions.” Despite the mandate that DOE revisit the PEF annually, when the Biden Administration took office, the PEF hadn’t been revised since 2000. The Natural Resources Defense Council and Sierra Club petitioned the Administration to update the formula.

The major reason for updating the PEF was that it was outdated and gave electric vehicles a much bigger boost in fuel economy equivalency than a more accurate PEF would provide. The 2000 PEF used something called a fuel content factor. The fuel content factor, as the Eighth Circuit noted, was explicitly included in the 2000 rule “to reward electric vehicles’ benefits to the Nation relative to petroleum-fueled vehicles.” The result was that manufacturers could use EVs to comply with fuel economy standards by using a PEF that significantly overstated the fuel economy benefits that the EVs were actually delivering, Manufacturers could, as a result, use fewer EVs to comply and could produce internal combustion engine vehicles that were less fuel efficient given the inflated PEF.

DOE initially proposed a new PEF that eliminated the fuel content factor altogether. The intent was to significantly lower the imputed fuel efficiency for electric vehicles when manufacturers used them to comply with fuel economy standards. But auto manufacturers pushed back hard on the proposed revised PEF, arguing in comments to the proposed rule that the transition to a new PEF was too abrupt. Instead, they argued that the fuel content factor be continued or phased out more slowly.

DOE responded to the auto industry concerns about an abrupt shift in the PEF by issuing a final rule that phased out the fuel content factor over three years rather than eliminating it immediately. In other words, DOE listened to the auto industry’s concerns and responded to them by making the PEF somewhat less strong in its first three years.

The Eighth Circuit threw out the new PEF on the grounds that the statutory language directing DOE to establish a PEF doesn’t authorize a fuel content factor. The language is very broad and included as a factor “the need of the United States to conserve all forms of energy and the relative scarcity and value to the United States of all fuel used to generate electricity.” DOE argued in the Iowa case that the language gave the agency ample room to transition the PEF’s stringency by phasing out the fuel content factor rather than eliminating it immediately.

Relying on both Loper Bright v Raimondo and the major questions doctrine, the Eighth Circuit rejected DOE’s argument. It gave no deference to the agency’s application of the governing statute to a very complicated set of facts and said that the statute could not be used to promote electric vehicles without express Congressional delegation under the major questions doctrine.

Now that the new PEF has been thrown out, under the court’s ruling the old PEF goes back into effect for compliance with the CAFE standards. The entire question of CAFE compliance is up in the air right now: Congress has zeroed out penalties for failure to comply; NHTSA is also claiming that the Biden standards are illegal and that the agency will “exercise its enforcement authority regarding all existing CAFE and medium- and heavy-duty standards in accordance with the interpretation set forth in this rulemaking.” But if auto companies do attempt to comply, the court has directed that the old 2000 PEF should be used. Of course the old PEF favors electric vehicles much more heavily than the Biden PEF and uses a fuel economy factor indefinitely rather than phasing it out. So the result of the court’s decision is to exacerbate the problem it claims the new Biden PEF created: EVs will be weighted more heavily than they should, allowing automakers to use fewer of them for compliance purposes and allowing internal combustion engine vehicles to be less fuel efficient.

The long term effect of the decision in Iowa v. Wright, however, may come back to bite the auto industry. Perhaps that’s why the Alliance for Automotive Innovation, which represents much of the auto industry, intervened in the lawsuit to defend the Biden PEF. DOE is mandated by statute to update the

PEF and cannot, under the court’s ruling, do anything to favor electric vehicles in setting the formula. As a result, a redone PEF should estimate the true efficiency of electric vehicles, eliminating the subsidy they’ve been getting for the past 25 years.

Reader Comments