Climate Politics Down Under

Australia is leaping from the frying pan into the fire.

Australian climate politics has been strange if not chaotic. And in terms of climate policy, things seems to be going from bad to worse.

This is partly a function of general political upheaval. In an enlightening 2018 paper, three University of Melbourne law professors (Baxter. Milligan, and McRae) traced the developments from 2007 to 2016. During that time, they say, only once in 2007 did the government have majority control of both houses of parliament, and “moments of alignment between the intentions of the House of Representatives and the Senate” were at “historically low” levels. have been historically low. There has also been strong polarization on the climate issue, as “all Australian political parties have dug in their heels and refused to negotiate on the issue of climate change regulation.” They found that “over the course of the decade’s 3,652 days, only once, in late-November 2009, was there a bipartisan vision for a suite of climate change legislation.” That consensus lasted little more than a week. Thus, they say, “[i]t is fair to describe Australia’s climate policy over the course of the past decade as a festival of misadventure.” As in the U.S., “[t]he general approach of the two major political parties has been aggressive and confrontational with little room for consensus.” Over the decade, there has been a clear feedback loop between the perceived political legitimacy of the country’s leaders, and their climate change policies.

The current Australian political situation is not encouraging, to say the least. An upset election this year saw the Liberals (who are actually the conservative party) win a majority of the House and the Prime Minister’s office. Their coalition fell short of a majority in the Senate, leaving smaller parties with the balance of power. From what I’ve read, the coalition can probably scrape up enough votes from right wing minor parties to pass much of its legislative agenda. The Liberal’s strong showing, according to the NY Times, was “thanks not just to their base of older, suburban economic conservatives, but also to a surge of support in Queensland, the rural, coal-producing, sparsely populated state sometimes compared to the American South.”

To American ears, there is more than a small echo of our own 2016 election in this. And an article in Forbes explains that Australia has in fact lined up behind Trump on climate issues: “Both countries have continued to invest in coal power, with Australia looking to open the world’s largest open-air coal mine adjacent to the Great Barrier Reef. During COP24 discussions held last year in Fiji, both countries reiterated their commitments to coal and explained that they had no plans to phase out their coal-fired power-plants.” Not surprisingly, the current government plans to let renewable energy targets expire, with no intention of replacing them. The current minister for disaster response says he doesn’t know if climate change is manmade. Unlike Trump, however, the government’s official position is that it remains committed to fighting climate change with AU$ 2 billion in incentives of various kinds — though this actually amounts to only one percent of the government’s budget.

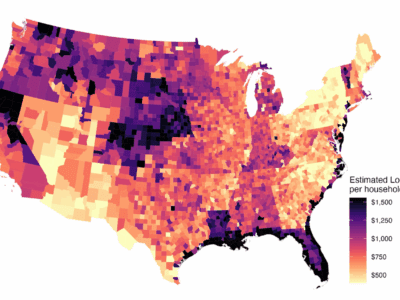

In some ways, the situation is worse in Australia than in the U.S. Australian carbon emissions have been on the rise, which looks likely to continue, whereas the U.S. trend has been mostly downward. Sixty percent of Australian electricity still comes from coal, more than twice the percentage in the U.S.

There are, however, a few bright spots. As in the U.S., state governments have shown leadership. New South Wales (home of Sydney) remains committed to achieving zero-net emissions by 2050. South Australia has a less ambitious emissions target. 2018 saw AU$ 20 billion in investment in renewable energy, with 15 Gigawatts of new generation under construction. About the only good news is that Australia will hit its 2020 renewables target thanks to a spate of new projects. Whether renewables will continue to grow after current incentives end is anyone’s guess.

In the meantime, the effects of climate change on Australia are getting pretty dire. As in other parts of the world, heat waves, drought, and wildfires are on the rise. The Great Barrier Reef is at risk. Public opinion may be changing. But so far, a majority of Australian voters seem not to have gotten the message.

Reader Comments

2 Replies to “Climate Politics Down Under”

Comments are closed.

Dan – Melbourne is not in NSW, FYI

Sean — Thanks for pointing out the mistake. I would blame it on a Legal Planet intern or staff member, if we had any. I’ve corrected it now.